The Evolution of the Modern Emergency Exit

Courtesy of russellstreet/Flickr

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about the design evolution of the emergency exit—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

When designing a commercial structure, one safety component must be designed right into the building from the start: egress.

Egress refers to an entire exit system from a building: stairs, corridors, and evacuation routes outside the building. Each state’s building code specifies a certain number of means of egress, depending on the size and purpose of the structure.

Simply put, there have to be enough doors, corridors, and stairs for every occupant to exit in an orderly manner in the event of an emergency.

Historically, the biggest threat to architecture has been fire, and architecture has evolved to resist it. In the 1700s, the best that building occupants could do in the event of a fire was to shout for firemen, who would bring the “fire escape”—essentially a cart with a ladder on it.

Courtesy of Reliance Fire Company

Fire escape methods became incorporated into architecture with the invention of the scuttle. The scuttle looked like a modern skylight with an attached ladder, allowing one to access the roof, at which point that person could walk onto a neighbor’s roof and climb down through his scuttle.

Many cities required that scuttles be incorporated in new construction, and it was the first time that architecture was regulated for the sake of fire safety.

By about 1860, New York began to require means of egress in tenement buildings. Landlords, of course, often went with the least expensive egress option: rope.

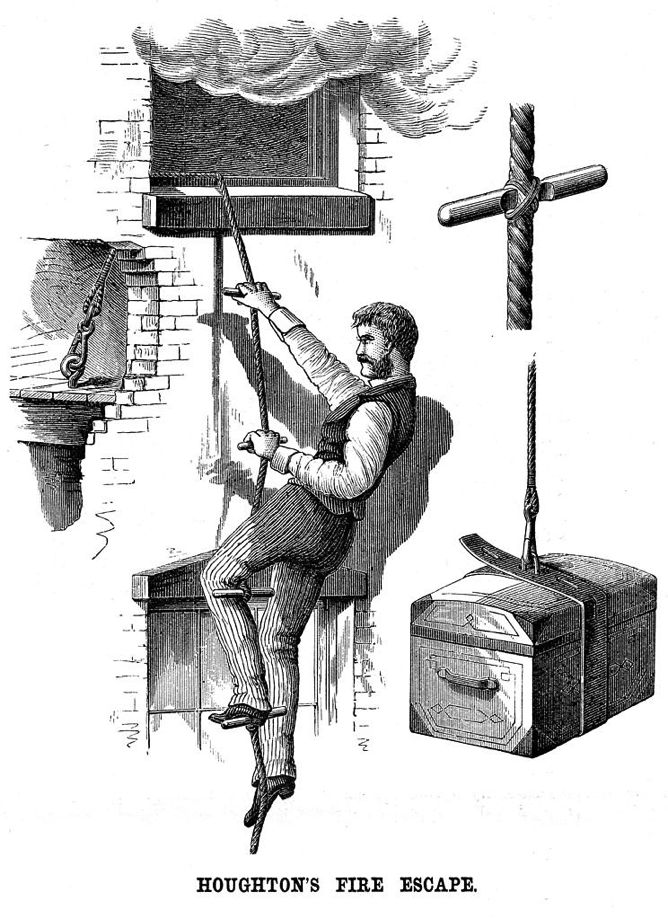

Courtesy of Scientific American/Wikimedia Commons

Using ropes or ropes with baskets, people were meant to lower themselves to the ground. Advertisements for rope basket storage units included fake cabinets, hollow refrigerators, and empty washing machines.

One engineer actually thought that instead of dispatching the ropes from indoors, archers could shoot the ropes up to the higher floors.

Another patent proposed individual parachute hats, with accompanying rubber shoes to break a fall.

There were also fire escape slides, which were marketed to schools as both emergency devices and playground equipment.

By the 1870s, fire escapes had become permanent iron structures. Some were just straight ladders clamped to walls, while others were the angled ladders more resembling stairs. But in true disasters, fire escapes didn’t suffice.

Courtey of Ken Ilio/Flickr

New York’s Asch Building was required to have three means of egress. The developer insisted the property would just be used as warehousing, so rather than installing three stairs, he was allowed to put in two stairs and a thin fire escape.

The owner rented the top three floors of the Asch Building to the Triangle Shirtwaist Company.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out in the Asch Building and spread quickly.

Workers on the 10th floor were able to survive by taking the stairs up through a fire exit to the roof. Workers on the eighth floor were by and large able to get out by taking the stairs down.

But workers on the ninth floor were trapped. Only a few people on the ninth floor knew about the 10th-floor exit, and most didn’t know to go upstairs. Allegedly, one of the doors out of the building was locked—though even if it wasn’t, the staircases that would have provided egress were too narrow and winding to hold the number of people who needed to escape.

Photo by Brown Brothers/Kheel Center at Cornell University

A number of workers tried to use the outside fire escape, but it collapsed under their weight. It was from the windows of the ninth floor that many workers, desperate to escape the flames and smoke, fell or jumped to their deaths.

As a result 146 people died, most of them women, right in the middle of Greenwich Village.

The building, however, was fine. It was a fireproof structure, which is why, at the time, no one really thought it needed egress. The Asch Building, now called the Brown Building, is part of New York University.

Courtesy of Richard Howe/Flickr

Exits and egress were a problem, people thought, for the tenements and poor quality buildings. Popular logic was that if a building was first class and noncombustable, the occupants could be safely locked inside.

The Triangle fire proved that architecture couldn’t protect people. People had to protect themselves from architecture. After the Triangle fire, the National Fire Protection Association started collecting data and studying effective egress.

Fire escapes, it turns out, just didn’t work.

Because they weren’t commonly used, fire escapes were often in states of disrepair or eroded by the elements. Even if they were maintained, fire escapes were not accessible to people with disabilities, the young, the elderly, and women who were hamstrung by their long skirts.

Most importantly, since people were not accustomed to using fire escapes, they often didn’t know where they were located.

Generally speaking, people try to leave a building the same way they entered it, and the modern fire escape is designed for this logic. They are the first place you would think to go in an emergency. They are the stairs. Or rather, they look like normal staircases, but they are truly pieces of emergency equipment: enclosed in fireproof walls, sealed with a self-closing door, and covered in sprinklers and alarms.

Courtesy of MySafetySign.com/Flickr

Because the fire stairs work perfectly well as stairways, they’re often the stairway in a building. Rather than spending the money and space on an opulent lobby with a grand, sweeping stairway, new construction tends to just have elevators and fire stairs.

Today, fire stairways need to be “rated,” meaning they need to be enclosed in a construction that won’t melt or allow the fire to penetrate as quickly as a nonrated wall. This is why the stairs are always shoved off into a cold, industrial-looking tower, no matter what the building looks like from the outside.

The rated towers and other emergency structures are now modeled with egress software such as Exodus, which allows architects and consultants to plug in the measurements of the building, its emergency equipment, the maximum number of occupants, click “play,” and watch digital people escape the pixel flames.

This software works because humans generally behave predictably in emergencies. In a state of panic, people don’t want to go places they haven’t gone before, or use devices they’ve never seen, or suddenly see if they can catch a rope shot with a bow and arrow. The way egress works now is in keeping with the way we use buildings everyday.

Rated towers might be ugly, expensive, and space-consuming, but they help save lives. In 2012, there were 65 deaths in nonresidential structures, which are the buildings with the heavy regulations and rated stairways. This number is already down from 2003, where there were 220 deaths in nonresidential structures.

Advances in egress make external fire escapes look primordial, but there’s still something beautiful about them, even the ones no longer in use. Fire escapes are a physical reminder of how we evolved past being a culture that says, “Here’s a rope. Good luck, buddy!”

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.