A History of Skyjacking and the Evolution of Airport Security

Photo by Joel Robine/AFP/Getty Images

Roman Mars’ podcast 99% Invisible covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we cross-post new episodes and host excerpts from the 99% Invisible blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

This week's edition—about skyjacking—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

When the government started to oversee aviation in 1958, hijacking wasn’t technically a crime. The early design of airport terminals reflected this. Airports were more like train stations. You walked through the terminal and onto the tarmac, and sometimes straight onto the plane itself, without flashing a ticket or showing anyone your identification.

Then in 1961, an epidemic of hijackings began.

The first wave of hijackers all wanted passage to Cuba. May 1, 1961, was the first American hijacking, perpetrated by Antulio Ramirez Ortiz, an electrician in Miami. Ramirez got on a Key West–bound flight, held a knife to the pilot’s throat, and announced that he had been approached to assassinate Fidel Castro, and wanted to go to Havana to warn him.

In the second phase, the skyjackers broadened their horizons to more distant lands. There were skyjackers like Raffaele Minichiello, an Italian-American Marine who hijacked a plane from Los Angeles to Rome. He was hailed as a hero upon landing and served only 18 months in prison; the Italians refused to extradite him. Minichiello was a good-looking guy, and actually ended up with a role in a spaghetti Western film.

All the while, hijacking wasn’t considered a serious threat by airlines or passengers. It was more of an inconvenience than anything else. The passengers assumed that if the plane was hijacked, they would simply be flown down to Havana, where the hijacker would be taken off of the plane. Maybe they’d have to spend the night in Havana. Maybe they could catch a show and buy some cigars and rum and have a good story to tell back in the United States.

Photo by AFP/Getty Images

Since passengers weren’t yet demanding extra security, the airlines fought to keep things exactly as they were. Security screenings would alienate customers, the airlines worried, and if they treated all their customers like criminal suspects, people would opt to drive to their destinations instead of fly.

Whenever the idea of physically screening all passengers was suggested, the airline lobby would shoot it down and force the Federal Aviation Administration to come up with the weakest, most tepid security improvements. After all, a hijacking typically cost an airline $20,000 to $30,000, whereas X-ray screenings and security personnel would cost millions. For the airlines, the smart financial choice was clear: Put up with the hijackings, comply totally, and keep the customer experience on the ground the same.

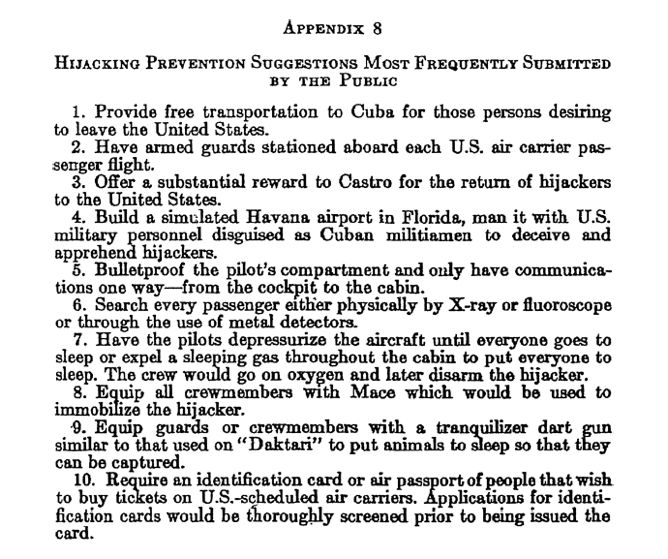

Still, something had to be done. In 1968, the FAA created an anti-hijacking task force to come up with solutions that would be palatable to the airlines. They even invited the public to submit suggestions.

The most common suggestion was complete capitulation. The pilots should simply provide free transportation to Cuba for those persons leaving the United States. Another tactic that was seriously considered by the FAA was to build a phony Havana airport in south Florida. In this plan the hijackers would believe they were landing in Havana but when they got off the plane, they’d be arrested by U.S. agents. Alas, the fake airport was too expensive.

There were other zany solutions, like a hijacker ejection seat. There was also one patent for an injector seat, which would have a “hypodermic injection apparatus, arranged for driving the needle of a hypodermic syringe through the seat cushion and into the passenger, to instantly sedate or kill the passenger.”

Courtesy of Brendan Koerner

Ultimately, the FAA realized that there was one place you had to stop on your way to a plane, and that was to get a boarding pass or purchase a ticket. The FAA solution therefore was to train the ticket agents in “twenty-five behavioral cues” that might indicate trouble. These were things like: “not maintaining appropriate eye contact,” “not caring about your luggage,” or “wearing military surplus gear.” If ticket-takers saw any of these behavioral traits in a customer, they would very discreetly ask that they go to a room on the side and be searched.

As you can probably imagine, this solution proved to be a failure.

The solution we all know they came up with—screening everybody and their luggage with x-ray machines and requiring ID—wasn’t seriously considered until one hijacking changed everything. In November 1972, three fugitives hijacked Southern Airways Flight 49. They wanted $10 million and threatened to crash the plane into the Oakridge National Laboratory near Knoxville, Tennessee, if they didn’t get it. At the heart of that laboratory is a uranium 235 reactor; all of a sudden, everyone realized that an airplane could be a weapon of mass destruction.

Southern Airways didn’t have $10 million, but it delivered $2 million to the hijackers when they landed in Tennessee. The hijackers, who had drunk all the liquor on the plane, didn’t bother to count the money, and they flew on to Havana, where they were captured by Cuban authorities. Crisis averted. But the hijacking was a wakeup call for the airlines and the government. Shortly thereafter, on Jan. 5, 1973, came the mandated order for universal physical screening. Much to the airlines’ dismay, the screenings were to be carried out by private contractors that they would hire.

The public conception of the hijacker changed dramatically in the '80s, in specific response to the TWA hijacking in 1985. All of a sudden hijacking was associated with Islamic terrorism.

Courtesy of Susan Gardner

Once we had the famous image of the pilot with a gun to his head, leaning out of the cockpit, we completely forgot about the more quaint hijackers, who just wanted some money and a free trip to Havana, and began to think of hijackers as terrorists.

Of course, 9/11 furthered the image of hijacker as terrorist, and the airplane as a weapon of mass destruction. After 9/11 the U.S. government formed the Transportation Security Administration* and took over the job of screening passengers before flights.

Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

For this story, Mars spoke with Brendan Koerner, author of The Skies Belong to Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking.

To learn more, check out the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show.

99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.

*Correction, June 26, 2014: This post originally misstated the name of the Transportation Security Administration as the Transportation Safety Administration.