What’s That Thing is Slate’s column examining mysterious or overlooked objects in our visual landscape. To submit suggestions and pics for future columns, drop us an email.

The InterContinental Mark Hopkins San Francisco hotel on Nob Hill is a legend. Mark Hopkins, Jr.—abolitionist, early Republican, well-known cheapskate, the child of first cousins who went on to marry his own first cousin—sailed from New York to San Francisco in the Gold Rush days of early 1849. Perhaps it was the long sea journey around Cape Horn that inspired him, along with Leland Stanford and others, to build the Central Pacific Railroad, part of America’s first transcontinental railway. Hopkins died before the mansion his wife-slash-cousin wanted on Nob Hill was finished (his final resting place, a 350 ton granite tomb in Sacramento, Calif., wasn’t ready for him either).

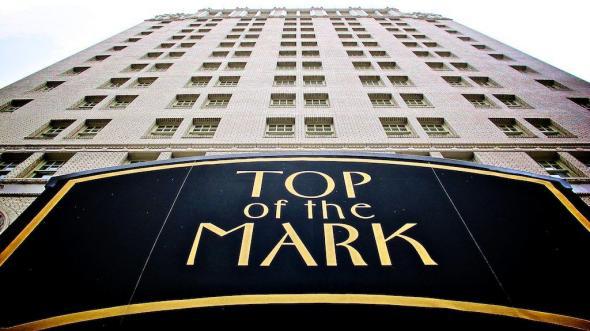

His widow lived on Nob Hill for a while before moving back east to marry a guy 22 years her junior. The mansion was lost in the fires after the 1906 earthquake. In 1926, the hotel named for Hopkins opened on the site. Today the bar at the top—the Top of the Mark, formerly the hotel’s penthouse—is as famous as the central-casting fog that swirls around it. First renowned as a farewell spot for sailors heading off to war, today the bar is typically packed with dancing tourists and seated locals, and a nightly crop of guys named Mark celebrating their birthday in high San Francisco style.

Courtesy of markheybo via Flickr

Waiting to ascend to this San Francisco landmark on a recent evening, we noticed a small blue star by one of the elevators in the lobby. Surely it had something to do with medical care—just what one might need after a few of the 100 kinds of Martinis served upstairs. But what exactly does it mean?

The symbol indicates that the elevator is big enough to hold a stretcher. If you’re going to get carried out of a bar, you’ll at least want to go in horizontal comfort, right?

The blue symbol itself is modestly known as the Star of Life. Originally designed by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and trademarked in 1977, it’s since become the general symbol for emergency medical services. At its center is the Rod of Asclepius, the snake-and-staff symbol for medicine (just one snake—it’s not a Caduceus, which has two snakes). Apollo was the father of Asclepius; their names are the first two invoked in the original Hippocratic Oath. Zeus zapped Asclepius with a thunderbolt after the famed healer was caught raising the dead in exchange for cash. Futurist Silicon Valley bioengineering execs, you’ve been warned.

Around the staff and snake, the six points of the Star of Life signify the stages of EMS care: detection (by the general public); reporting (e.g. dialing 911); response; on-scene care; care in transit (the ambulance); and transfer to definitive care (a hospital, typically).

Image by GraphEGO/Shutterstock

This symbol appears in many EMS contexts—uniforms, ambulances, government websites. When it appears on an elevator, it typically means that that elevator is large enough to accommodate a 24” by 84” stretcher.

Brian Black, code and safety director for National Elevator Industry Inc., a trade association, told me that stringent building regulations mean that such commodious elevators, and the Stars of Life that mark them, are increasingly common. “The International Code Council’s International Building Code is the most-referenced building code in the U.S., and it requires an elevator that can accommodate an ambulance stretcher in all new buildings four or more stories above or below grade.”

What if you don’t see a Star of Life on any elevator in a building you live or work in? Different jurisdictions update their building codes at different times, and may amend the code when they adopt it, according to Don Zeni, a general manager at Lerch Bates, a leading building consultancy. So even a compliant elevator may not have a Star of Life on it. And in many buildings, Zeni adds, the elevator suitable for stretchers might be a service or freight elevator that isn’t visible to the general public.

Courtesy of Mark Vanhoenacker

Still, elevators in older buildings may not be compliant. Or there may not be an elevator at all. The National Fire Protection Association’s Robert Solomon pointed out to me that fire crews are often the first responders, and will look out for the Star of Life as carefully as EMS personnel. If there’s no elevator at all, you may find yourself leaving the building on a stair chair. “Very handy in New York City,” Solomon notes.

What if you get stuck in an elevator, and you can’t, you know, call EMS personnel, because your phone doesn’t work? Brian Black says the industry is looking at installing repeaters in elevator shafts, “but these improvements are still in the exploratory phase.” Better connections in elevators wouldn’t just make it easier to tweet the latest gossip from the bank you don’t actually work at. It’s also a safety issue on those rare occasions when someone doesn’t know you’re stuck—think of the 85-year-old nun who spent four nights in an elevator absorbed in prayer, between meals of celery sticks and cough drops, while her sisters were at an out-of-town convention.

For more on the workings of elevators, don’t miss previous columns on the hole in the elevator door and the mysterious S button.

Got an idea for a future column? Send along a pic or a description to whatisthat@markvr.com.