Over the past 25 years, Tobias Frere-Jones has created some of the world’s most widely used typefaces. He has taught at the Yale University School of Art since 1996, gives lectures around the world, and has work in the permanent collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Here at the Eye, Frere-Jones is sharing a post from his new blog about what happened when two of his favorite things—typography and New York City’s history—led him to a surprising discovery about a forgotten part of his hometown.

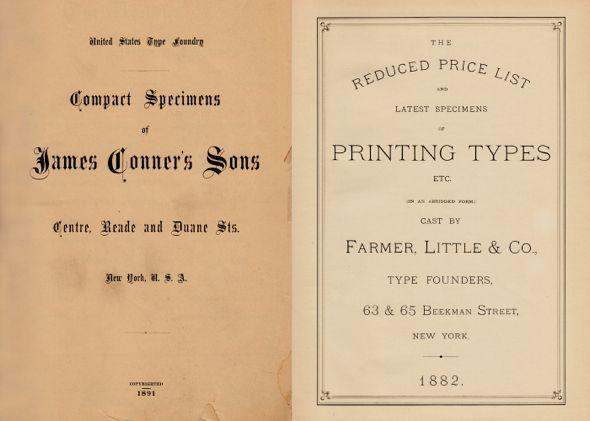

I love old type specimen books. Any foundry, any period, it doesn’t matter. They will have me hypnotized. But I don’t usually linger at the title pages. Who would, really? All the fun and exciting stuff comes after that: the impossibly small text faces, the spectacular display faces, all the sample uses variously dowdy and natty. So a long time went by before I noticed a trend in specimens from New York foundries, particularly through the 19th century:

Courtesy of Tobias Frere-Jones

These addresses are pretty close together. No—they’re really close. Wait, some of these are less than a block apart. OK, hang on, stop. I needed to figure this out.

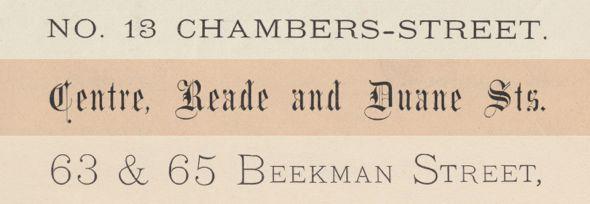

I re-read Maurice Annenberg’s Type Foundries of America and Their Catalogs, tracked down business directories of the period, and spent too much time on Google Earth. But I was able to plot out the locations for every foundry that had been active in New York between 1828 (the earliest records I could find with addresses) to 1909 (see below). All of the buildings have been demolished, and in some cases the entire street has since been erased. But a startling picture still emerged: New York once had a neighborhood for typography.

Copyright © 2014 Tobias Frere-Jones

But why were they concentrated here, and not scattered throughout the city like the warehouses, the breweries, the stables, and the rest? This wasn’t the old Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, all packed together at the end of the island. The city was two-and-a-half-miles long by the middle of the 19th century, with full development extending to 14th Street. Land would likely have been cheaper up north, and the business directories show other kinds of factories operating well uptown. But even as type foundries expanded or merged, they remained in this small area. What did they find so vital about this one neighborhood?

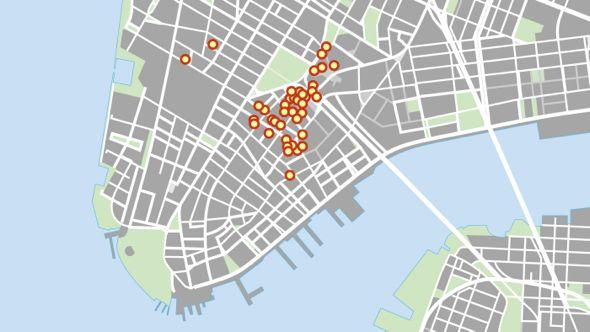

Courtesy of Tobias Frere-Jones

My guess is that they were following the newspapers. New York had dozens of newspapers back then, with most headquartered around Park Row, later nicknamed “Newspaper Row.” Crews composed and recomposed dozens of pages for every issue, with some papers publishing multiple editions throughout the day.

Hand-set type was cast in “type metal,” an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony. Lead’s low melting point made it easy to cast, while the other metals added hardness and stability. But despite all the precise chemistry, type would still wear out. And delicate Victorian letterforms at tiny sizes (six and seven point were common sizes for text) could not have resisted fatigue for very long. Each paper would have placed large and frequent orders to keep their composing rooms running and their issues printing. So the foundries would have been staying close to their best customers.

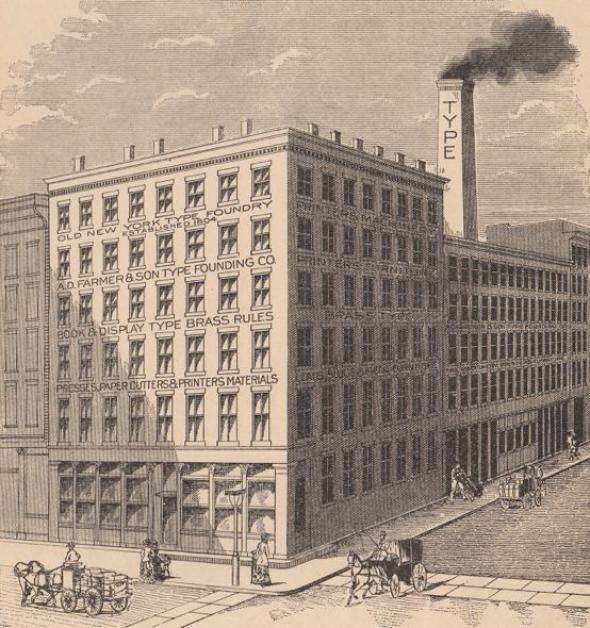

Via Wikimedia Commons

The newspapers were, in turn, huddled around their most frequent subject and adversary, City Hall. And for its part, City Hall had been built at the start of the century on “The Commons,” an open area then at the northern edge of the city. But that frontier was moving outwards so rapidly that City Hall was well inside the developed city when construction finished after nine years.

Copyright © 2014 Tobias Frere-Jones

So it seems that New York’s “Type Ward” was placed here by the blind arithmetic of history. If the local government had sought its permanent home 10 or 30 or 50 years later, City Hall would be somewhere else, with the newspapers and type foundries following.

Roughly half of New York’s foundries joined the American Type Founders conglomerate when it formed in 1892, and the remaining companies were bought out by 1909. ATF soon consolidated all of its operations in Jersey City, and the old Type Ward vanished. At the center of the upheaval was a young and rapidly growing foundry, across the river in Brooklyn.