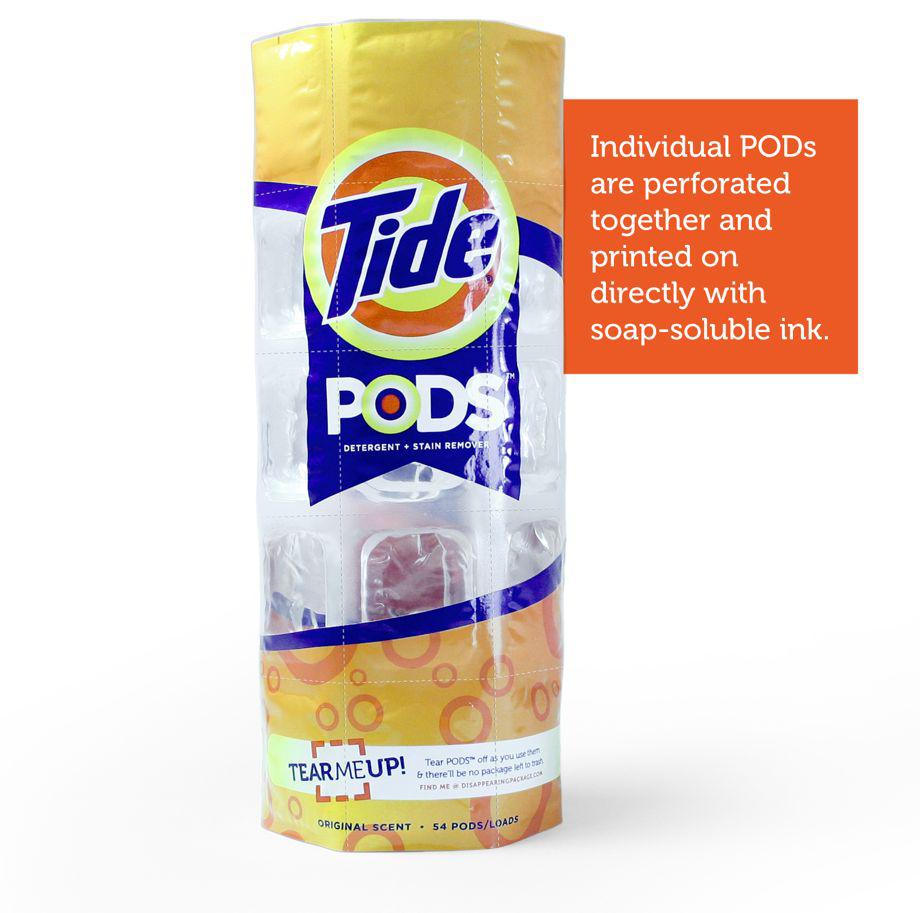

When Aaron Mickelson decided to tackle the problem of packaging waste for his Pratt Institute master’s design thesis The Disappearing Package last year, he wanted to go further than minimizing package size. So he gave five leading household products clever and radical eco-friendly makeovers that eliminated packaging altogether.

In a prototype redesign for Tide PODS, he stitched together a sheet of laundry pods, with brand info printed on the back of the sheet in soap-soluble ink, so that the packaging would disappear with the last pod, sparing the landfill a useless plastic storage tub or bag.

Courtesy of Aaron Mickelson

Courtesy of Aaron Mickelson

Courtesy of Aaron Mickelson

He created an accordion-like perforated stack of Twinings tea bags, wax-lined for freshness, with no need for stapled labels or strings or paper storage boxes.

Courtesy of Aaron Mickelson

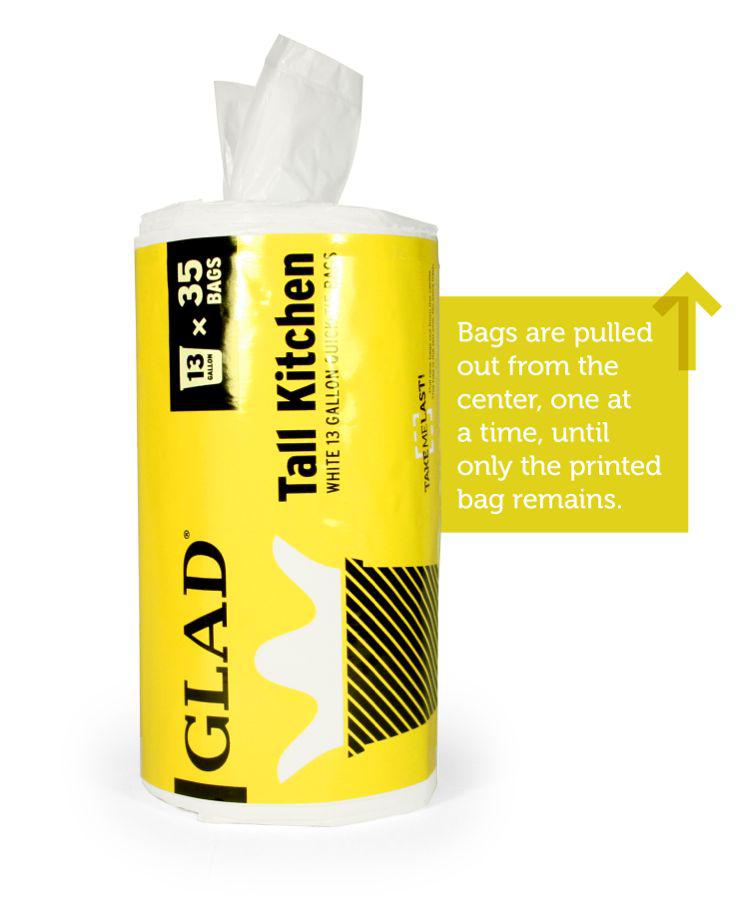

Brand information for a roll of Glad trash bags was printed with traditional oil-based inks on the last trash bag in the roll, which instead of being kept in a box, served as the packaging itself.

Courtesy of Aaron Mickelson

And he designed a prototype for a Nivea soap box made from septic-safe, water-soluble paper that simply dissolved in the shower, leaving nothing but soap behind.

Courtesy of Aaron Mickelson

The ideas generated plenty of enthusiastic buzz when he first shared his thesis with the world in 2013. So when it popped up again on Designmilk a few weeks ago I couldn’t help but wonder if Mickelson’s great ideas had gained any real-world traction since last year.

“While I was designing my thesis, I selected each brand carefully based on my understanding of the openness of their design culture or the size of the positive impact I thought they could have,” Mickelson wrote in an email. “When it was published, if nothing else, I wanted to establish a dialogue with these brands. I sent letters to creative leads at each company. Not a one responded, though several wordlessly connected with me on LinkedIn.” Mickelson added that data tracking has shown him that his site has received more than 100 visits from what appear to be users at Procter & Gamble (makers of Tide), “but none has ever so much as emailed me.”

The designer said that he has been approached by other large brands and startups around the world who are “interested in reducing their impact” and “captivated by the concept of eliminating packaging waste altogether.” But trying to develop disappearing packaging in the real world has taught him a thing or two about the chasm behind a good idea and a workable solution.

Mickelson said that there are four basic entities involved in creating packaging: the brand, the designer, the supplier, and the manufacturer. “The brand has a problem, the designer creatively solves it, the supplier makes the materials, and the manufacturer puts it all together,” he said. “Sometimes these can be the same company or person (some manufacturers create the materials they work with; some brands have in-house design teams), but in most cases these are the four roles.”

Before he hit publish on his thesis, he said, “I would have told you that the greatest roadblock to making disappearing packaging a reality would be the brand: evil big companies, run by evil corporate cogs, who would rather revel in their evilness than consider a new idea. These are people, or so I believed, who didn’t care about the environment. What I have come to learn is that many companies are run by thoughtful, eco-minded individuals. Even the ones who are maybe willing to sacrifice on the eco front still nonetheless realize that their consumers are demanding a difference in the way things are done.”

But he said that the “toughest link in the chain” is packaging manufacturers and material suppliers, “who seem entirely apathetic about the idea,” he said. “Literally, getting to a finished package or even a working prototype has been frustratingly impossible.”

Mickelson said that the materials needed to implement his solutions—like water-soluble paper and ink—are already being fabricated in the United States. Nevertheless, he said, “on countless occasions, I have gone to a supplier trying to make prototypes for large brands who would make enormous orders if only I could get some material samples and specs, and had no reply. Exactly one time I was able to get a rumpled pack of water-soluble paper (at the wrong size), and that was the last time I was able to get in touch with that supplier.”

The designer said he’s been bolstered by interactions with like-minded people worldwide who dream of a packaging-free future, and isn’t giving up yet. But changing the status quo doesn’t happen in a day.

“The package design system is founded on waste,” Mickelson said, offering an example. “Many companies these days opt to manufacture packaging in China, for cost savings, but virtually every package made there is immediately stuffed into a plastic bag to withstand being stacked on a ship and carried half-way around the globe. Those poly bags typically end up in the trash.”