Designboom tipped us off to a monumental feat of ingenuity, will, and resourcefulness by Jesse Krimes, a 31-year-old artist from Philadelphia who stealthily made a 39-panel mural piece by piece using contraband prison sheets, hair gel, plastic spoons, and New York Times clippings while serving a 70-month jail sentence that ended last September.

Krimes was sent to federal prison in 2009 for possession of cocaine with intent to distribute, the year after he graduated with a B.A. in studio art from Millersville University of Pennsylvania. He spent his first year awaiting sentencing in a 22-hour-per-day lockdown in his cell, banned from venturing outside for fresh air or sunlight. To cope with the isolation and the shock of being a nonviolent drug offender in a medium security prison surrounded by Aryan Nations leaders, Russian mobsters, and other violent criminals, he started making art. Fellow inmates commissioned portraits to send to loved ones on the outside, paying him in jailhouse currency (books of stamps). Soon he began teaching art classes to other inmates, who converted the old piano room into a de facto art studio.

Krimes said that carving out a singular identity as resident artist kept him out of trouble in an atmosphere charged with gang violence and allowed him to make a cross-section of allies amid racial divides. “They called me ‘the independent,’ ” Krimes told me in a phone interview. “Artwork facilitated conversation. And it humanized me to some of the guards. They saw me not as an inmate but as a person.”

Courtesy of Sarah Kaufman

In prison there was no TV or Internet, but he had access to books and newspapers. He reread philosophy texts he had studied in college and started reading the New York Times, finding himself emotionally drawn to dreamy images of idealized vacation destinations in the travel section. But he was also struck by how often news stories of man-made and natural disasters occurring in those same places depicted an alternate reality. And again by the ubiquitous ads for consumer goods that both entrap the masses in self-imposed symbolic prisons of their own and foster a cult of materialism he says played a role in motivating his own errant choices.

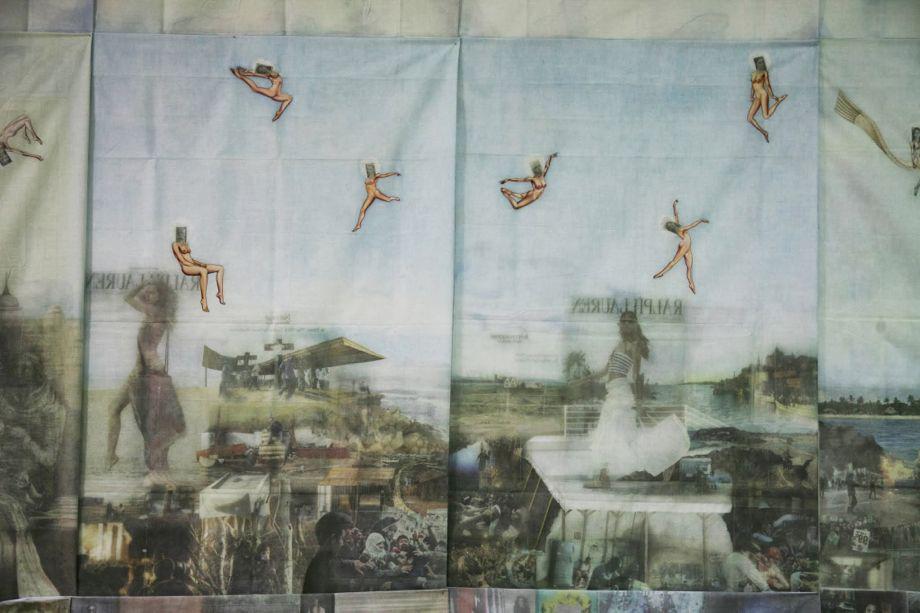

Krimes began plotting his mural, which would attempt to grapple with those contradictions. He clipped images and traced a series of naked dancing women by hand using colored pencils, based on photos of ballerinas in the arts section. He bought hair gel from the prison commissary and was allowed to order canvas from an art catalog, but he never intended to make his great prison masterwork on such a conventional material, procuring clean prison sheets from a friend who worked in the laundry room to use as his primary material instead.

Courtesy of Sarah Kaufman

“Canvas is a boring material,” he said, adding that the canvas was used simply as a foil to avoid getting busted in a “shakedown” by any unsympathetic guards. “Defacing sheets is destroying federal property. But the mural is a product of its conditions,” he said, adding that appropriating sheets which he said are fabricated by prisoners at a profit to the institution, allowed him to reveal something integral about the experience. “I developed the mural as a way to transcend the conditions of prison and all the negative things that go on in that environment on a personal level; the work is personal and autobiographical, but it also is meant to expose the system.”

Krimes spent three years working on the 39-panel mural, which he mapped out in his head and worked on piece by piece. To make a panel, he would tear a prison sheet in half, dampen it with hair gel, then transfer images to the sheets using the back of a plastic spoon, a meticulous process that took about 30 minutes and required careful planning to fit in with his highly regimented prison existence. To avoid getting caught with the contraband art, he mailed panels one by one to his girlfriend, and assembled them after his release last September.

Courtesy of Sarah Kaufman

When Krimes got home, he had a job waiting for him at the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, where his boss allowed him to set up studio space to work on and display the mural. The finished work is called Apokaluptein:16389067, after the Greek origin of the word apocalypse; the numbers reference his Federal Bureau of Prisons identification number.

Krimes said that his profoundly isolating and dehumanizing prison experience had changed him not only as a person but as an artist.

Courtesy of Sarah Kaufman

“Before I went to prison I made sculptural pieces in three dimensions with metal and bronze casting and my work was very free and expressive,” he said. “Then when I went to prison I started doing this obsessive compulsive highly detailed two-dimensional drawing and printing process.”

Courtesy of Sarah Kaufman

But he also found an artistic calling of sorts. Working in isolation for five years with limited resources and materials has created an urgent desire to create and collaborate and to help criminals who are locked up to maintain a connection to the outside world.

Courtesy of Sarah Kaufman

“Now that I’m free and I can move and have a body and a voice I want to reach back and collect inmate’s stories,” Krimes said. He has in mind a project that would use animation and stop motion film to tell those stories and give a face to the faceless, projecting images onto the facade of the African American Museum in Philadelphia, so the inmates in the prison across the street could look out their windows and catch a glimpse of themselves on the outside.