Ferran Adrià is one of the world’s most venerated culinary pioneers, a molecular gastronomist who used sophisticated cooking techniques and a multisensory approach to reinvent Spanish cuisine. His Michelin-starred restaurant elBulli became an international foodie destination that revolutionized the concept of eating with an avant-garde tasting menu of some 40 dishes.

Brett Littman, the executive director of The Drawing Center in New York City, had a memorable meal there with his wife in 2010. “It wasn’t necessarily the best tasting, but it was the most exciting and profound dining experience I had ever had,” he told me by phone. He was struck not only by the immense technicality of the cooking and the wit behind many of the chef’s sensory tricks—like a nutmeg-sprinkled ostrich “eggshell” made of flash-frozen gorgonzola that had to be manually cracked open and consumed using only your fingers in 18 seconds before it puddled into oblivion—but also by Adrià’s ability to upend diners’ expectations. “That’s what made it art, really,” Littman said, pointing out that the chef was challenging preconceived notions in the way that great artists always do.

After the meal he bought a copy of Adrià’s A Day at elBulli and noticed that it included images of lists and diagrams that the chef used to record ideas and document the immense body of technical knowledge required to generate a constant stream of ambitious new dishes. Fascinated by the way those outside the confines of the visual art world used drawing as part of their creative process, Littman wrote to the chef asking if he might consider sharing some of those visual materials with the public. The product of that collaboration is Ferran Adrià: Notes on Creativity, the first major museum exhibition to focus on the role of drawing in the master chef and his team’s creative process. It runs from Jan. 25 to Feb. 28 at The Drawing Center in NYC and will tour Los Angeles, Cleveland, Minneapolis, and the Netherlands.

Courtesy of elBullifoundation

Adrià closed elBulli in 2011 and is currently building a foundation to its legacy that will open in 2015 on the redesigned site of the former restaurant. It will house a permanent exhibition showcasing the restaurant’s history and culinary evolution while a creative team will continue to publish its research in Bullipedia, an online database designed to house the collective elBulli wisdom about techniques, products, and ingredients for future generations.

As curator of the exhibition, Littman made several trips to Barcelona, Spain, over a span of two years, spending long hours with Adrià culling materials for the show, which includes hundreds of notebooks filled with everything from loose sketches for new dishes to ideas, collaged photographs, lists, tables of ingredients, and cooking methods. They communicated through a translator, but Littman said that the chef spent much of the time conveying his ideas with pen and paper.

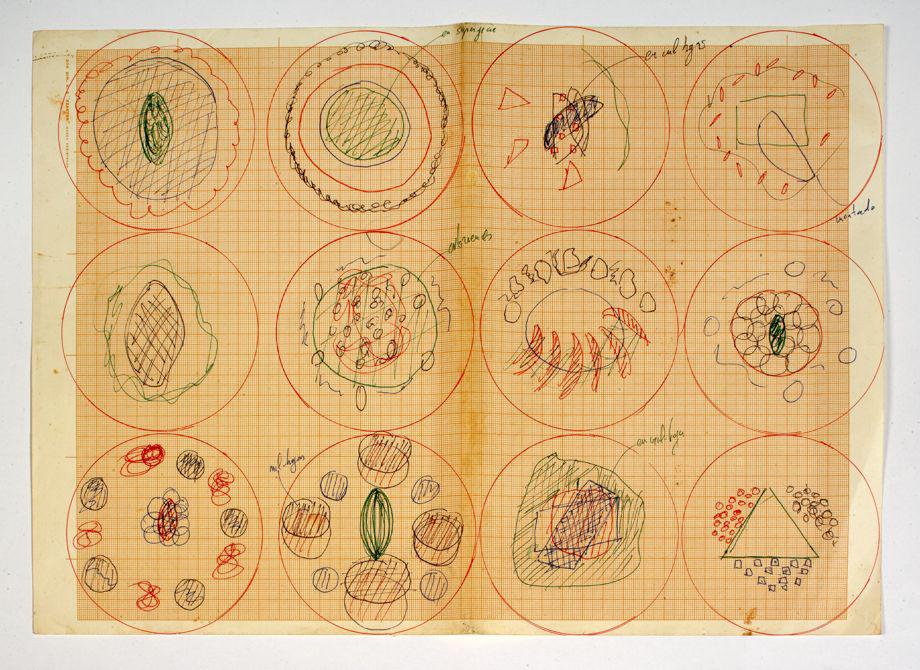

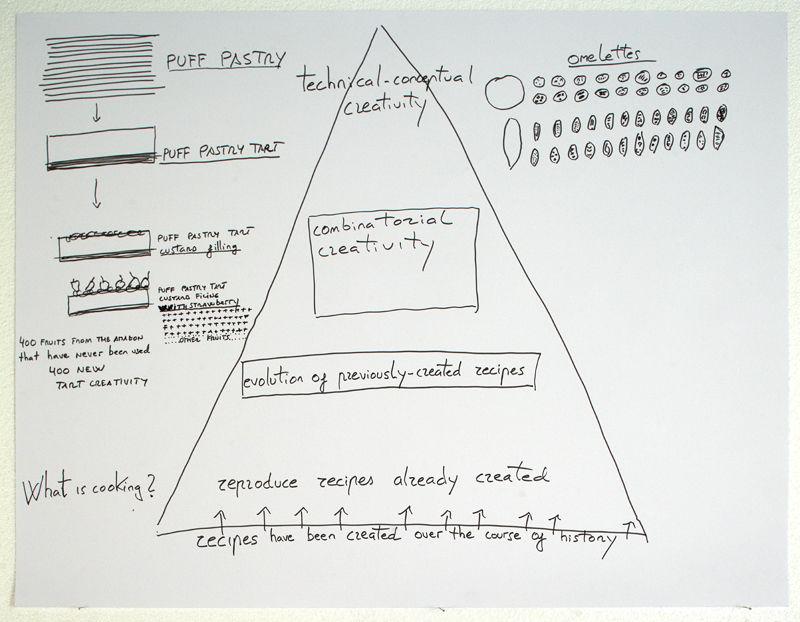

The exhibition includes plating diagrams like the one seen above that Adrià used to help create new dishes. “He started by drawing shapes, focusing on color and texture and placement without a specific recipe plan,” Littman said, adding that the chef would then reverse-engineer dishes based on this exercise in form rather than content.

Courtesy of elBullifoundation

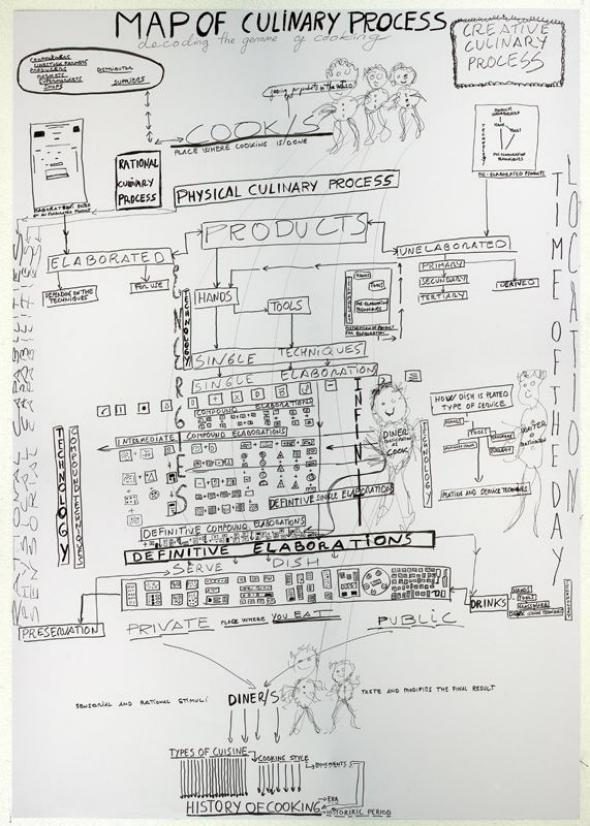

“There’s a long history related to art and food,” Littman said. “His drawings aren’t necessarily great representations of food, they are used more like mental maps or flowcharts to visualize the way that he thinks.”

Unlike many kitchens which have more in common with military operations than innovation hubs, Adrià created a creative lab that encouraged participation from staff, who Adrià trained to communicate in images, making attribution difficult for a majority of the visual materials in the show.”Drawing is an analog for thinking,” Littman said. “Visualization was the lingua franca of that kitchen.”

Courtesy of elBullifoundation

The exhibition will also include architectural drawings and a model of the new elBulli Foundation headquarters, 3-D plasticine models that are used as a visual aid for chefs to faithfully reproduce individual dishes, 60 framed color drawings by the chef that explore his “theory of culinary evolution,” and drawings and prototypes from collaborations with graphic and industrial designers who helped to develop elBulli’s dishware, utensils, menus, and graphic identity and to codify the restaurant’s working methods.

These include pictograms created by graphic designer Marta Mendez designed to help classify groups of ingredients, culinary cartography diagrams developed with graphic designers Bestiario to trace the evolution of food throughout history, and specialized tools developed to execute elBulli dishes with the help of Swiss industrial designer Luki Huber, who created everything from serving dishes to “aroma balloons” and hard candy curlers.

As part of the exhibition, the Drawing Center is producing 1846, a 90-minute film that is essentially a photo montage of all 1846 dishes that Adrià served at elBulli, set to a soundtrack that includes ambient sounds of the elBulli dining room. This six-minute video preview will whet your appetite.