It’s our Christmas edition of What’s That Thing, Slate’s column examining mysterious or overlooked objects in our visual landscape. To submit suggestions and pics for future columns, email us.

At this festive time of year, you might take note of the undecorated Christmas trees that are habitually perched atop buildings under construction. What’s up with those?

The tree is an ancient construction tradition. There are many such rites associated with a new edifice including the laying of foundation stones, the signing of beams, and ribbon-cuttings. But what’s particularly charming about the construction tree is that it isn’t associated with the beginning or the end of construction. Rather, the tree is associated with the raising of a building’s highest beam or structural element. Hence the name of the rite: the topping-out ceremony. It’s a sign that a construction project has reached its literal apogee, its most auspicious point.

Courtesy of Kate Ulman/Daylesford Organics

Given what our shelters do for us, it’s easy to see the raising of an edifice in ancient, almost primal terms. So when a new building reaches its final height, it’s not surprising we’d mark the occasion with a ceremony. But why celebrate with a tree?

In fact, the first topping-out ceremonies didn’t use trees. In 8th-century Scandinavia sheathes of grain were the plant material of choice. But as topping-out ceremonies spread throughout northern Europe, trees were a natural evolution. In cultures closely tuned to the natural environment, there may have been a pleasing visual analogy between the growth of a tree and the raising of a building. Perhaps a prayerful humility was conjured by the (temporary) elevation of a tree above the top of a man-made structure.

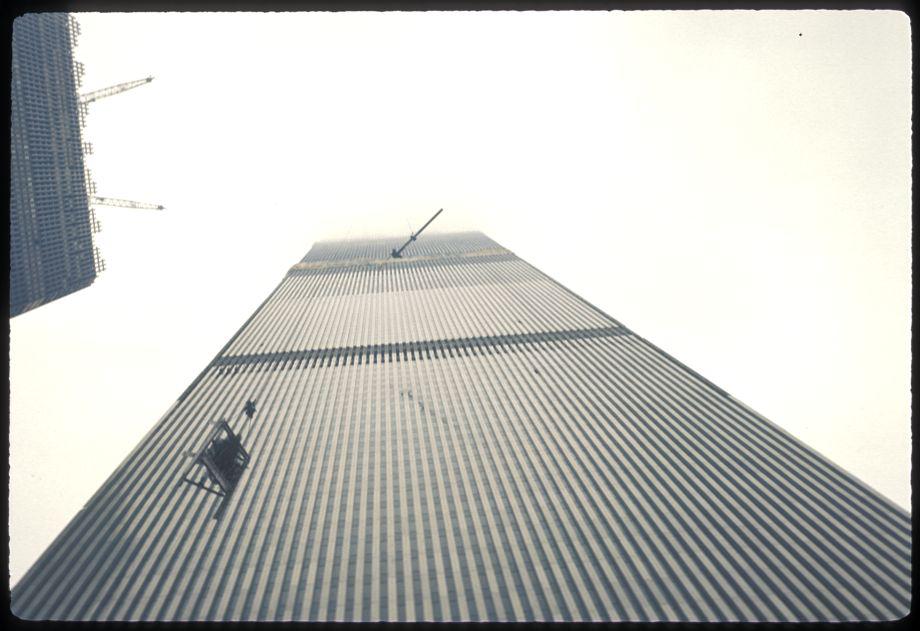

The ancient topping-out ceremony has survived mostly intact in this era of high-tech, high-altitude edifices. In the U.S., particularly on large projects, the final beam is often signed, and an American flag may accompany the tree skyward. The purpose of the ceremony—at least for shining skyscrapers—is usually couched in comfortably post-pagan terms: a celebration of a so-far safe construction site, an expression of hope for the secure completion of the structure, and a kind of secular blessing for the building and its future inhabitants.

Courtesy of the Skyscraper Museum and VIVA2

But superstition remains a part of the ceremony, especially on smaller projects. Elizabeth Morgan, an architect at Kuhn Riddle in Amherst, Mass., (and a childhood friend) told me that the general understanding among her colleagues is that the greenery may “symbolize the hope that the building will be everlasting.” She also reports a vague sense among construction teams that “if you don’t do it, bad things will happen.”

Her colleague Brad Hutchison noted that ceremonies often involve a pine bough, not a whole tree. He remembers a wintry Friday afternoon ceremony when a pine bough was mounted on the ridge beam of a recently framed roof, an occasion celebrated with hot cocoa and beer.* “This is New England, so a lot of carpenters are/were sort of New Agey and took the tradition somewhat seriously,” he said. “New-Agey superstition and carpentry/building go well together, I think, and I’m sure most architects like to think of their buildings as having a ‘soul.’ There is something special about the moment when the ‘bones’ of a building are finished and exposed (before the sheathing and cladding go on).”

Liv Wyatt, another colleague, described a seemingly more makeshift version of the ceremony in which a broom, bristle side up, was lashed to the topmost beam. The beam and broom were raised together, and the broom remained in place until the roof decking went on a few weeks later.

Courtesy of the Skyscraper Museum and VIVA2

What about outside of America? The tree tradition reputedly remains strong in much of northern Europe (though a spokesman for the Shard, London’s glitzy new pyramid, told me that no evergreen topping-out ceremony took place). In Victoria, Australia, Kate Ulman, a farmer and blogger, recently attended a topping-out ceremony at her parents’ house. Their construction team had never been to a topping out but were familiar with the custom. This being Australia, in addition to a fir branch, they added—what else?—some eucalyptus. And there was cake.

What about in Hong Kong, where skyscrapers are a revered form of public art, and the resulting skyline dwarfs even that of New York? I contacted Julia Lau, a Hong Kong architect and the project manager for the construction of the extraordinary ICC Tower, the tallest building in this very tall city (and the seventh-tallest building in the world).

Lau told me that despite Hong Kong’s British heritage, Western topping-out ceremonies are rare. The main celebration is Chinese-influenced and takes place at the start of construction, with a roast suckling pig. On the (auspiciously numbered) date of the ceremony, a stakeholder in the building will bow three times while holding three pieces of burning incense—a pleading for a “safe and smooth-sailing project,” says Lau. Then the suckling pig is cut and shared with all the workers present.

Courtesy of the Skyscraper Museum and VIVA2

So what did Lau think of the Western topping-out tradition, with its evergreen tree or branches, and distressing lack of roasted pigs? She pointed out that tree-raising, which to many Westerners may first suggest some ancient hangover of humility or reverence for nature, also showcases the power and skill of the construction workers—to not only build this thing, but to casually lift a tree to the top of it.

But for her, the sight of greenery rising echoed the “birth of life” symbolized by the new building itself.

In this season of celebration—of a birth, and an evergreen tree, and even a resurgence of seasonal roasted pork products—it’s hard not to think she’s onto something.

See something from atop your sleigh (or broom, or new skyscraper) and wondering what it is? Email us a description or a pic.

*Correction, Dec. 19, 2013: A previous version of this blog post misspelled the last name of architect Brad Hutchison.