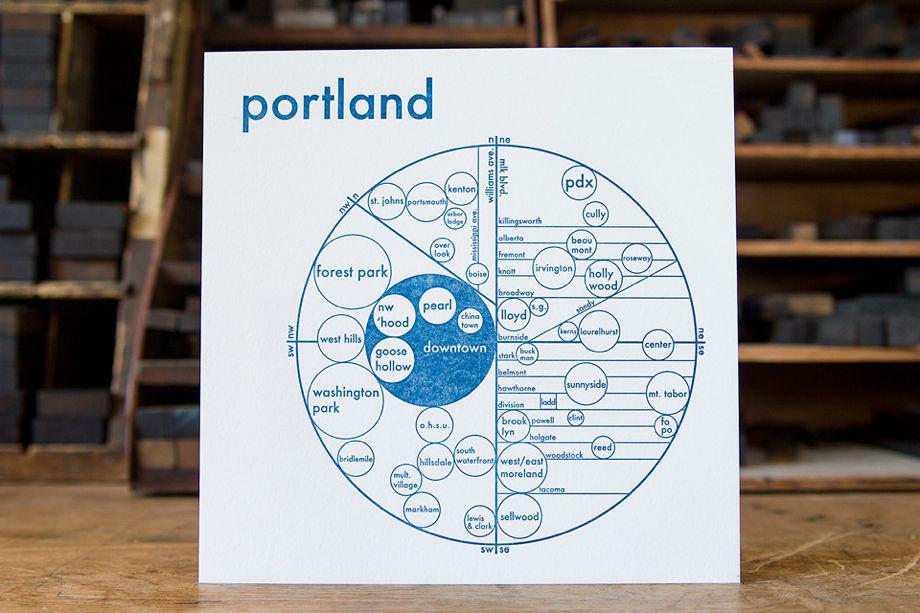

Archie Archambault was a philosophy major who moved to Portland, Ore., in 2009 after college and found himself getting lost. For all their practical uses, Google maps didn’t seem to really give him a local’s sense of neighborhoods, or how to navigate the city as a whole, or reflect his perceptions of how long it took to get from point A to point B. “I was super absorbed in the GPS,” he told me. “But a Google map has a scientific feel. I wanted to communicate the idea of a city on paper.”

So he drew a circle with a cross hair in it, dividing it into quadrants. Then he started exploring streets and neighborhoods by all means of transportation possible, getting an on-the-ground feel for the urban landscape. That first sketch led him to create his first map of Portland (above) and became the genesis of a quirky map-making process that he still uses today.

Courtesy of Archie’s Press

“I build a map in my head and then I talk with locals to see if my perception matches up with their experience of a city,” Archambault said, adding that he tries to informally poll the widest range of people possible, including his favorite insider resource: real estate agents. “They are the ones who end up naming emerging neighborhoods,” he says, “and who really know the whole layout of a city.”

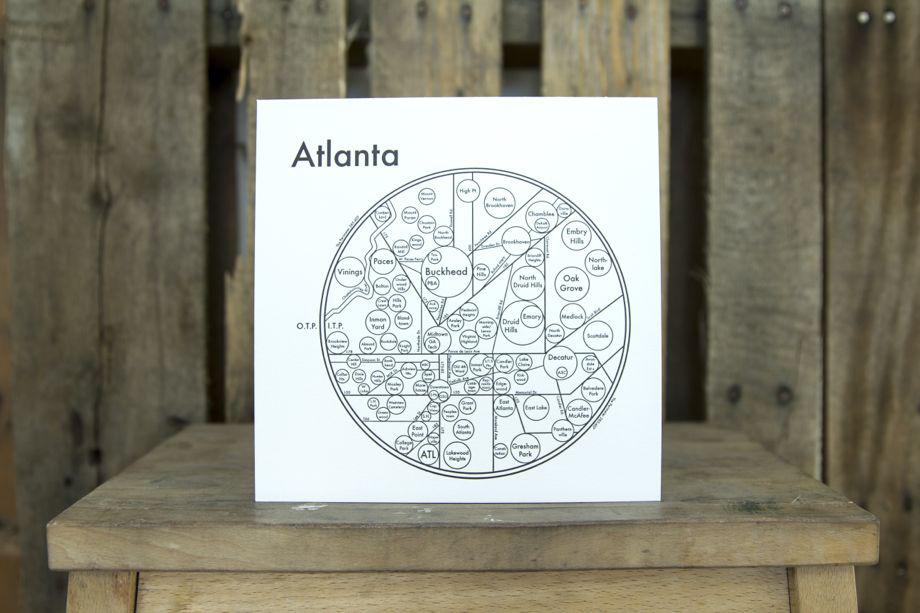

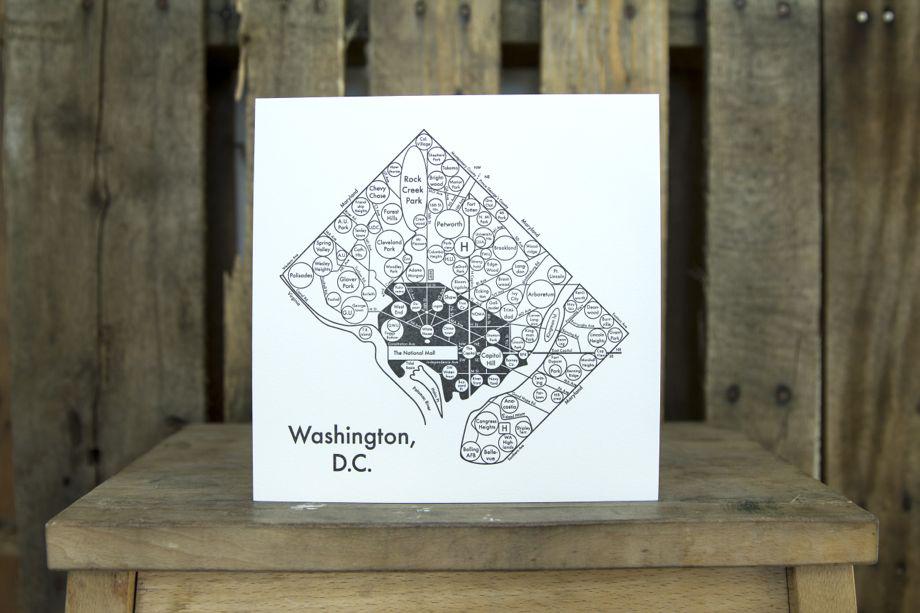

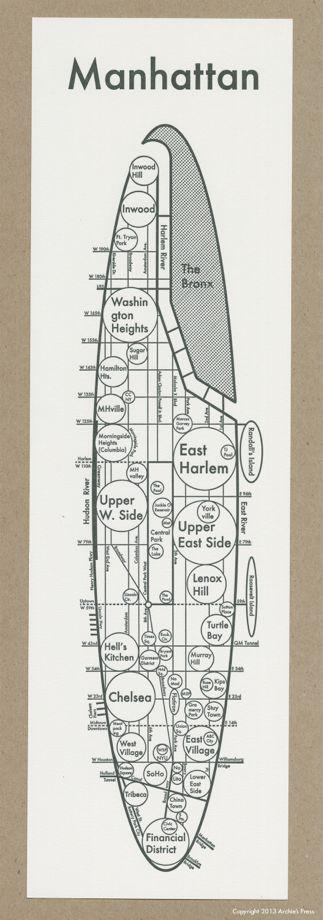

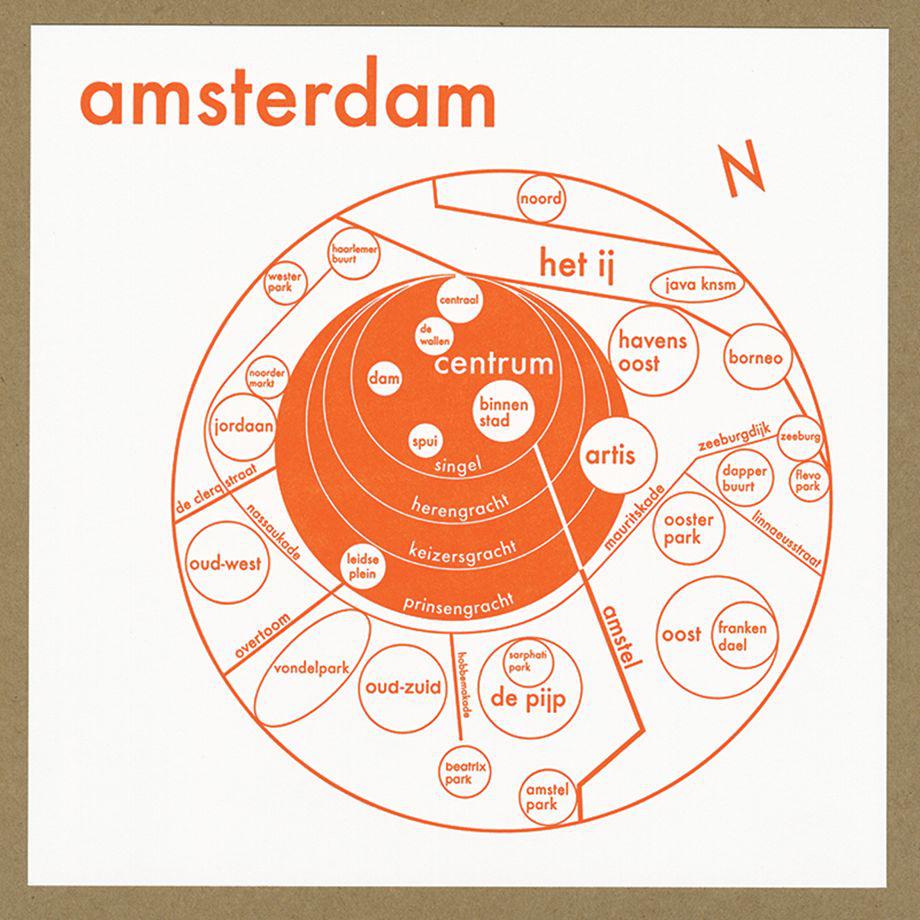

Archambault started printing maps on a 19th-century letterpress machine in 2011. Earlier this fall he launched a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund a four-city road trip and recently added maps of D.C., Atlanta, New Orleans, and Austin, Texas, to the roster of cities that includes Manhattan, Brooklyn, San Francisco, Boston, Seattle, and Amsterdam.

Courtesy of Archie’s Press

To do what he calls the “mental and cultural groundwork” to make each map, Archambault said he experiments with different modes of transport according to the culture and landscape of each city. In Atlanta, he drove everywhere, as locals do. In D.C. and New Orleans, he said, he spent all day on his bike. He said it was the easiest way to get around autonomously and at his own quick pace, to know which direction he was heading and create a mental road map.

Courtesy of Archie’s Press

The defining design aesthetic of Archambault’s minimalist maps is the use of typography and circles (though he adapts the design according to the city; D.C. is shaped like an imperfect diamond and the island of Manhattan is smoothed into a long oval). This makes his work part of a tradition of circular maps dating back centuries. And aligns them with circular transit maps designed to make sense of the transportation labyrinth in world capitals like Berlin or New York.

Courtesy of Archie’s Press

The use of text gives them something in common with more purely decorative, minimalist word-based maps that eschew terrain for typeface, or illustrated maps like The New Yorker’s legendary New Yorkistan cover, which offer social commentary by renaming or redrawing physical boundaries.

Courtesy of Archie’s Press

But Archambault isn’t trying to reinterpret reality; he wants to reflect it in a subjective way. He uses local names for neighborhoods. And while the maps have an abstract quality at first glance, he claims that they are meant to be used; while he strives to make them “beautiful and decorative-looking, the goal of each map is always the same: to understand and explain the city in the clearest, most concise, clear, simple way possible.”

Courtesy of Archie’s Press

Why circles?

“Mostly it’s an aesthetic decision,” he says. “The theory behind it is that a circle is the softest shape for the eye, so it’s easier to absorb information.” Most neighborhoods don’t have hard corners, he says. “The circle is the most important shape, it’s the simplest shape, the most beautiful.”

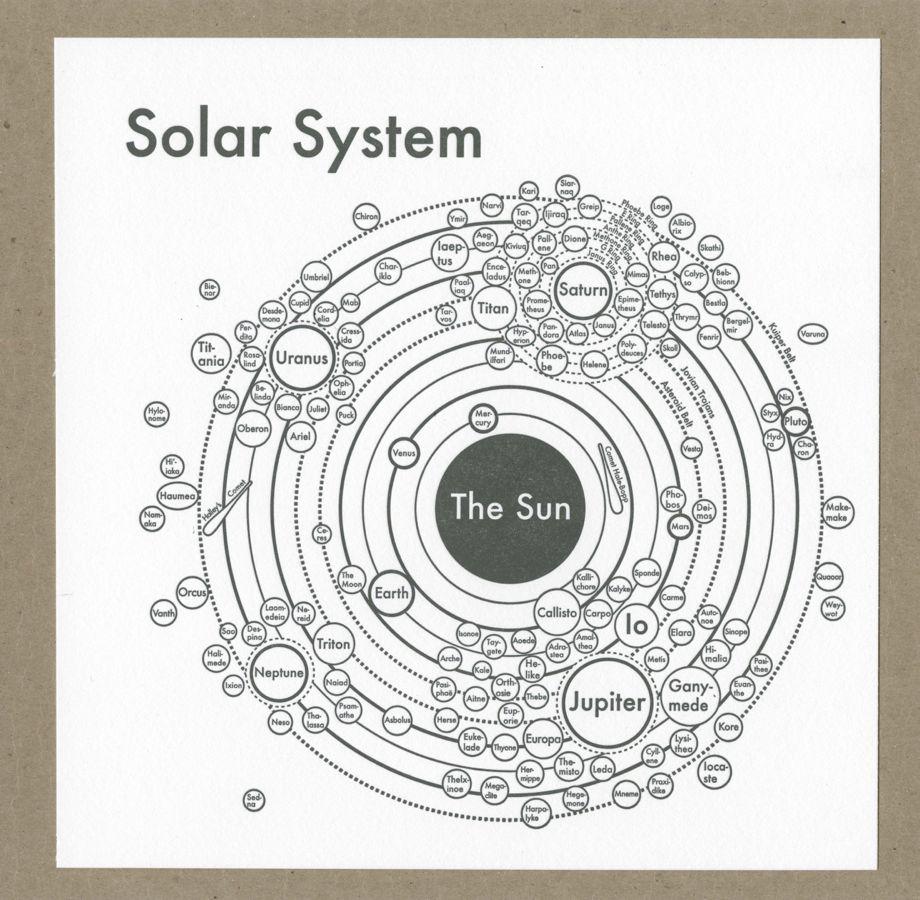

Archambault says he hopes to go on a longer version of his four-city road trip and map more cities. And a recent departure includes a map of the solar system. “That’s a direction I would like to move in,” he says, adding that finding this vocabulary of expressing space and the relationships between objects using circles has helped him to imagine a series of maps that help explain how other systems function, like branches of government or family trees.

Courtesy of Archie’s Press