For shocking previous editions of What’s That Thing, click here, here and (maybe) here. To submit your own suggestions—electric and otherwise—see the email address below.

What’s the ugliest thing about America the Beautiful?

Utility poles. And the wires strung between them. Those who have grown up in the U.S. generally don’t notice them––or how unsightly they look. But visitors from abroad are often astonished. In much of the rest of the rich world, utility lines are hidden, underground and out of sight.

Complaining about the wires draped all Gulliver-like across America isn’t just a European pastime; 19th-century Americans did the same. Samuel Morse, credited with the first deployment of utility poles, decided to foul America’s streets and skies only when efforts to run telegraph lines underground failed. Concerns that lines were unsightly and would require the ongoing destruction of trees were one reason Thomas Edison developed underground electrical wiring (for Brockton, Massachusetts).

Still, in an America without utility poles, we wouldn’t have received the photograph above from a reader in York County, Pennsylvania (that would be the York County whose official seal features an idyllic country road unmarred by overhead wires). What’s the purpose of the yellow mesh wrapped around the pole?

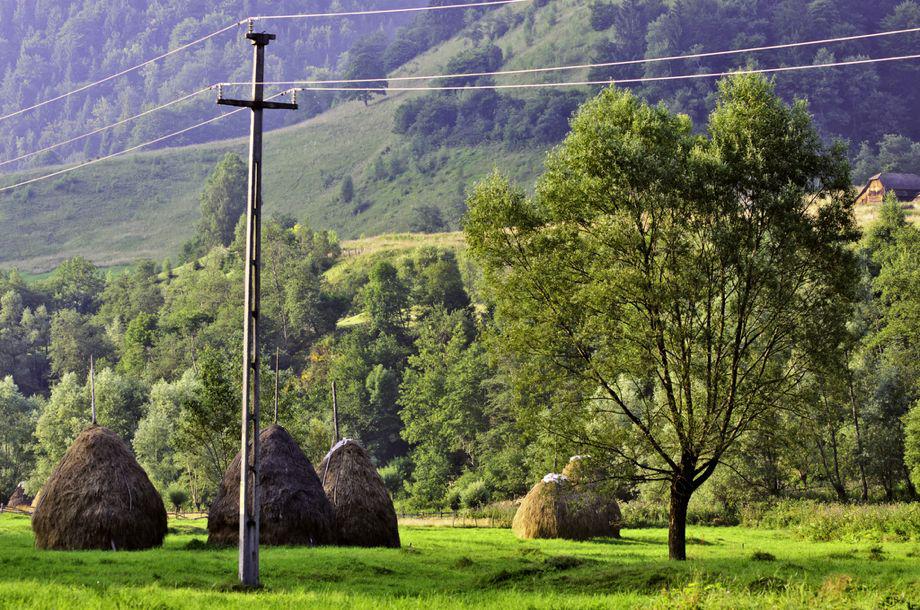

Image courtesy Horia Varlan via Flickr

Finding the answer took a bit of digging. Replies from various utilities companies included: “We do not use anything like that on [our] poles;” “It might be something someone placed there to hold a sign—just a guess from our folks in the field;” “I assume it was nailed there by a local consumer;” “I wish we could help you here;” “It could be marking a race course or a garage sale;” “Let us know if you find out” and “No one here has any idea.”

The answer eventually came from Greg Smore, a spokesman for PECO, a utility company in the Philadelphia area. The yellow meshes are called grid reflectors. Their purpose is to help motorists see and avoid utility poles. Since 2007, PECO has installed them on 77,000 of its 400,000 poles and plans to add more on poles located near roadways.

Why a wrap-around grid, instead of old-school circular reflectors?

The color and size of the bright yellow 12” x 8” grid reflectors were field tested for visibility and “proved to be the most effective and viewable at a wide range of angles,” Smore says.

It’s easy to wonder about the utility, as it were, of marking poles to prevent collisions. If you’re in a position where you’re about to hit one, then arguably you’re already out of control (you might be drunk, like this intoxicated but candid pole-smasher looking to crowdsource some legal advice).

On the other hand, collisions of cars and utility poles can be so serious that erring on the side of caution makes sense: Even those who survive a collision might be tempted to get out of the car—and risk electrocution. (Click here for a run-down on fallen power lines and cars, including pointers like “shuffling gives you the best chance to avoid being fatally electrocuted.”)

And collisions with utility poles create nightmarish risks for bystanders and first responders. Last summer in Los Angeles, a 19-year-old drove his SUV into a utility pole. Onlookers rushed to help, and stepped into pools of electrified water. Two were killed, and six were injured. The teenager was put on trial for manslaughter; his lawyer argued that Good Samaritans “should have known the inherent dangers associated with downed power lines and standing water.” (Underground lines can present dangers as well—that’s why you should dial 811 before you dig).

Image courtesy Channone Arif via Flickr

But apart from safety considerations, what about the aesthetic objections of those Americans who do take offense at all those poles and wires cluttering up the landscape?

Just as Vermont famously bans billboards and many American communities ban clothes lines (despite the “Right to Dry” backlash), many U.S. citizens are quite prepared to pay to keep utility poles and wires out of sight. The nonprofit Scenic America (slogan: “Change is Inevitable; Ugliness is Not”) notes that nine out of ten new American subdivisions feature underground utilities.

And there are other compelling reasons for American power to go underground. Compared to overhead wires, underground electrical supplies are much less vulnerable to interruption and damage from falling trees, wind and ice (not to mention intoxicated motorists). Underground lines don’t require the continual trimming back of nearby vegetation. And while composing “Bird on a Wire” may have helped ease Leonard Cohen’s depression, underground wires have never been implicated in the electrocution of bald eagles.

In fact, the only real advantage of above-ground wires is price. Underground utilities cost anything from a few to ten times as much to install. That’s a particularly important factor for America, a country that is larger and less densely populated than most. Maintenance on underground utilities, though generally required less often, is also a pain—think excavations and road closures.

But these cost calculations may be about to change, even for a continent-sized country like America. As David Frum wrote after the 2012 east coast blackouts, climate change and demographic trends (stronger storms, hotter heat waves, denser cities, and larger populations of those vulnerable to extreme heat) may make underground utilities much more cost-effective in coming years. In 2008, windstorm events in the U.S. caused 27 million customers to lose power. The UK, where underground utilities are more common, just experienced one of its worst windstorms in a decade. Despite 99 mph winds—and the fact that the storm was named for the patron saint of lost causes—only 270,000 homes lost power.

Something else you might notice on utility poles? Colored bands that wrap entirely around the pole. Positioned lower down, these too can serve as reflectors for motorists, according to Mike Hyland, an engineer and vice president of the American Public Power Association (they also occasionally serve as holders for “Yard Sale” signs, he laments). And higher up? They might be used to alert workers that “a double circuit on the pole is at different voltages,” says Hyland, or to mark poles for maintenance or removal.

A side benefit of such reflective bands is that they make it much harder for squirrels to climb the poles, according to P&R Technologies, a manufacturer. That’s good for electric companies, and for squirrels—though the news comes late for this little guy.

Image courtesy gb_packards via Flickr

If you see something out there you’re wondering about—above ground, or below—take a pic and send it to whatisthat@markvr.com.