The defining quality of the fashion designer Azedine Alaïa, now the subject of a major retrospective that just opened at the newly renovated Palais Galliera at the Musée de la Mode in Paris, is that his work has always been more about the design than the fashion.

“I make clothes, women make fashion,” he likes to say.

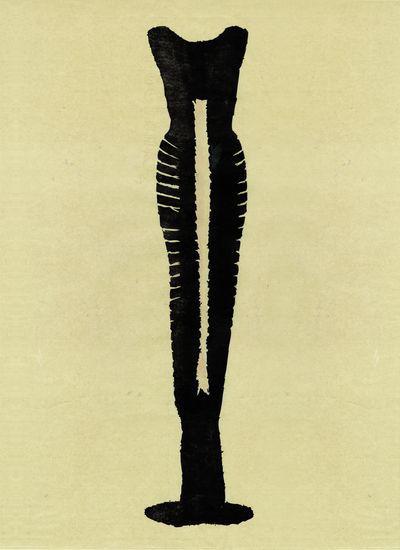

© Aurore de la Morinerie

Alaïa studied sculpture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Tunis before becoming a fashion designer, making clothes for private clients for many years before presenting his first collection in 1979. Often referred to as the father of the bodycon dress, and crowned in the ‘80s the King of Cling for his form-fitting pieces, Alaïa is known by critics, observers and the clients he has dressed—from Greta Garbo to Grace Jones and Naomi Campbell—for engineering garments that focus the conversation on a woman’s form. A woman wears an Alaïa dress; it never wears her.

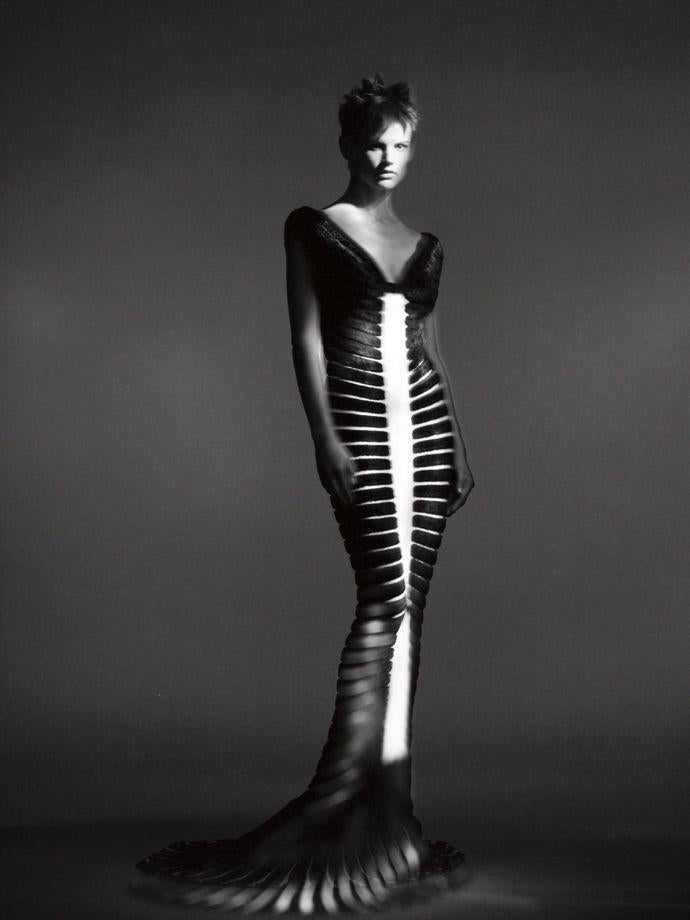

© Paolo Roversi

In the exhibition catalogue, curator Olivier Saillard says that Alaïa believes the success of a dress lies in its ability to make itself forgotten in favor of the woman it’s on. The designer’s creations have always been more about structure than ornament, Saillard writes.

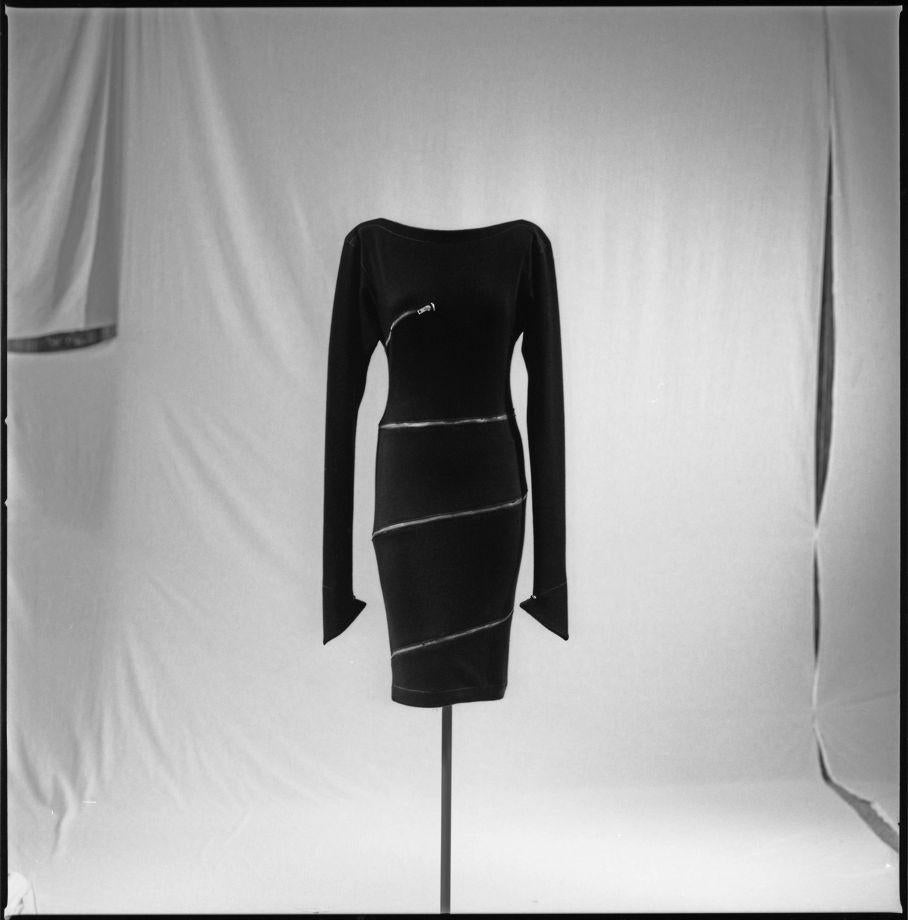

How does Alaïa achieve this effect? His dresses enhance the body using tricks such as complex stitching, exposed zippers, eyelet studs, mesh and stretch jersey to sculpt and accentuate his flattering silhouettes. Saillard calls the zipper Alaïa’s “ultimate jewel.” The use of zippers or bands of stretch jersey that extend around the silhouette of a dress is one of the sleights of hand that allows garments to compress a body’s flaws without restricting movement. It’s a trick the designer picked up in the ‘70s while designing costumes for the legendary Paris cabaret club Le Crazy Horse.

© Ilvio Gallo

The designer’s penchant for building timeless clothes that were meant to last rather than fleeting fashion makes makes it hard to date many of his signature looks. He stopped showing his collections during fashion week starting in 1988, preferring to stick to his own schedule and rhythm. And he isn’t afraid to openly criticize fashion heavyweights like Vogue’s Anna Wintour, with whom he has had a standing feud for years.

“I never followed fashion,” he says. “It’s women who have dictated my conduct. I’ve never thought of anyone but them because I am convinced that they have more talent than any stylist. You must understand the academy of their bodies in order to anticipate their desires. Over the years, I have followed the lessons of their silhouette. The shoulder is essential, the waist primordial. The small of the back and the derrière are crucial.”

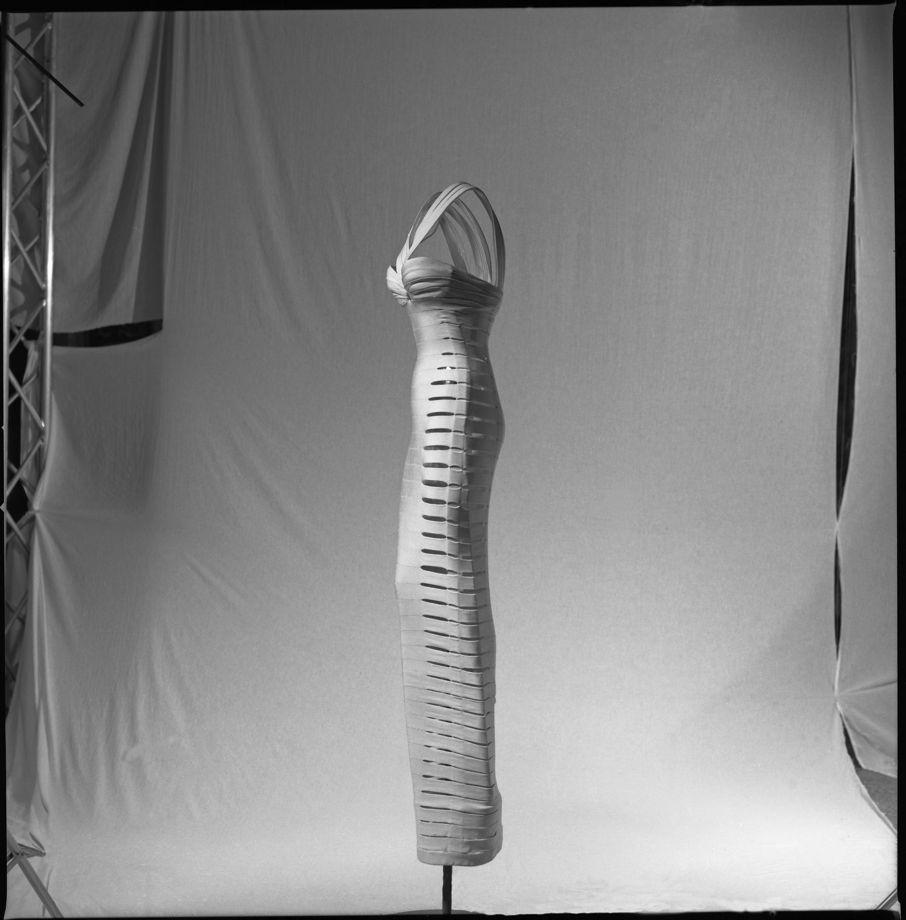

A long Alaïa dress from 1990 made with stretch rayon strips.

© Ilvio Gallo

Unlike many fashion designers who come up with ideas that they then try to project onto the human form, Alaïa begins from the ground up, following the architecture of a woman’s body.

“If I don’t have a model in front of me,” he says, “I don’t have an idea.”