Thinking about something other than the presidential race will probably be a healthy emotional break. Last week on my Current TV show, there were two separate segments about justice gone fundamentally awry and remedied in the end only by the perseverance of courageous lawyers, who time and again stood up against the long odds of overturning a conviction, sustained by the powerful sense that justice had been violated.

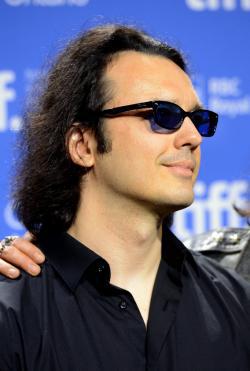

Damien Echols of the West Memphis Three told of the horrors of spending 18 years on death row, wrongly convicted because of a town’s anger and need for vengeance. And then Vanessa Potkin from the Innocence Project recounted how that organization’s efforts have now freed 300 inmates using the power of DNA evidence.

What can we learn from Echols and Potkin? First, our criminal justice system is fallible. We know it, even though we don’t like to admit it. It is fallible despite the best efforts of most within it to do justice. And this fallibility is, at the end of the day, the most compelling, persuasive, and winning argument against a death penalty.

Second, technology helps. Technology is neutral: It convicts and finds innocents. We must make it a regularized part of the system, giving defendants access to DNA testing and evidence whenever it might be relevant.

Third, as the Echols case makes so clear, coerced interrogations continue to be the bane of fair trials. Here too, technology has an answer. As one who was a prosecutor for many years, I can tell you that having a tape recording of interrogations would help everybody. It would make clear if there had been improper pressure exerted on a defendant or witness, and it would also protect the interrogating officer from false claims that such pressure had been brought to bear. The audio or video would record what had actually had been said, eliminating so many of the arguments on both sides about coercion.

The cost of recording interrogations is too insignificant to worry about. Every cell phone practically has the capacity to serve as a recorder. Jurisdictions as different as the state of Montana and the city of Los Angeles have in recent years moved to require recordings, and the results have been almost entirely positive, for prosecutors, for defendants, for the courts, for justice.