National Review, a magazine founded by the late William F. Buckley, is the intellectual leader of the conservative movement. It speaks for the agenda of deregulation and pure free-market theory that overtook and then destroyed our economy.

Back in 2004, National Review put a caricature of me on its cover and called me the most destructive politician in America. Why? Because, as the magazine pointed out in the accompanying article, I was the attorney general of New York at that time, and I and my office were pursuing wrongdoing in a multitude of areas. We were suing coal-burning power plants that were violating the Clean Air Act, we were suing the tobacco companies because of their illegal marketing and deceptive practices, and we were suing virtually all the major Wall Street investment banks for committing fraud and violating their duty of honesty to the public. The feds were doing nothing about these problems before we did. We sued the largest mutual fund companies—which were gaming the market—leading to billions of dollars in refunds to customers and lower fees totaling billions of dollars. Again, this was something the feds were unwilling to do. And, as the article pointed out, we were suing predatory lending companies, long before 2004, and I was warning that subprime debt could be both harmful to the borrower and toxic to the economy. The federal government tried to shut down our effort.

It was these actions that led the National Review to deem me the most destructive politician in America. Frankly, I wish that the financial world had paid attention to what we were saying at a deeper level. At the time, evidence of the brewing crisis of 2008 was visible, and even though we tried to be heard, especially about predatory lending and subprime debt, the voices of the dangerous ideology of deregulation won out. Clearly, we have all paid an enormous price.

There was a core logic to our cases. As someone with a deep faith in competition and the market, I also know that markets only work with tough enforcement of the rules that guarantee competition and fair play—and that the pressure to break those rules only gets stronger as the amount of money involved gets larger. There is also the more purely theoretical principle that I feel most of us believe in—that it is important for our society that the most powerful always be subject to the rule of law, and the least powerful be entitled to the protection of the law. Our cases tried to vindicate those two core principles.

Unfortunately, those most responsible for creating the financial crisis have escaped paying any price—we have a Justice Department that seems incapable of framing important cases. It would rather focus on steroids in baseball than structural malfeasance on Wall Street or torture by the government.

One consequence of this failure to hold accountable the malefactors who helped cause the crisis is that they are now trying desperately to rewrite history, disclaiming any responsibility and pretending that events simply did not occur as they did.

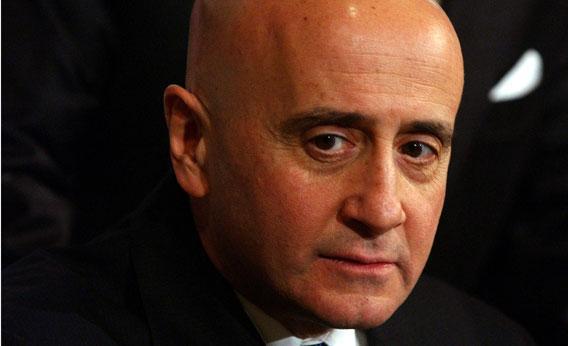

A small group of individuals whom I prosecuted has been using multiple platforms and venues to attack me personally and distort the record of these cases I prosecuted. Most recently, Ken Langone—who was the chair of the Compensation Committee of the New York Stock Exchange for several years—went on CNBC to level another round of attacks: “Look, this guy is a master at deception. … He is like a spoiled kid, ‘I’m here, pay attention to me.’ ”

Langone should feel free to speak up. It is his right, and I bear him no ill will for stating what he views to be his case. Yet I also feel it incumbent upon me to set the record straight—not because the individual cases are so important, but because the larger principles we were trying to vindicate surely are, and because so much of what has been said is simply outrageous.

So let’s talk for a moment about the case against Ken Langone and his role on the NYSE Compensation Committee. The New York Stock Exchange, at the time a not-for-profit, paid its CEO Dick Grasso more than $200 million over a series of years. A report done for the board of the Exchange by Dan Webb, one of the most respected prosecutors in the nation, found that Grasso was overpaid by at least $144 million, and that Langone and the compensation committee handled the matter improperly!

This position was supported by multiple judicial decisions. In the end, an appellate court found that because the New York Stock Exchange had converted to a for-profit, the attorney general’s office lost jurisdiction over the case. This was a ridiculous decision, and the dissenting opinion said it was “meritless on its face.” As it was. The judge who wrote the opinion is one of the most political judicial actors I have ever encountered. More important, the failure of Langone to act properly is established in excruciating detail in the Webb report and subsequent judicial opinions.

That Grasso was paid in excess of $200 million by a board composed of the CEOs of the very companies he was supposed to regulate is overwhelming evidence of just how corrupted our corporate governance system had become, and remains. The behavior of the New York Stock Exchange board during this era is a perfect demonstration of the interlocking conflicts of interest and corruption that permeated our corporate leadership.

During his appearance on CNBC Wednesday, Langone and the host also recalled my last appearance on their network and spoke disparagingly and dismissively of the case against AIG and Hank Greenberg, the former CEO of AIG, that my office also prosecuted. Langone said: “He kept pointing to a report with no relevance to the Hank Greenberg case. It had relevance to the case in Connecticut.”

The record here is crystal clear: AIG and Hank Greenberg were charged by the New York Attorney General’s Office—while I was attorney general—with fraud and deceptive accounting practices. The company settled for $1.64 billion, at the time the largest payment in history. Let me quote from the New York Times’ reporting of the settlement: “Under the settlement reached with the Justice Department, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the New York Attorney General’s office, and the New York State Insurance Department, AIG acknowledged it had deceived the investing public and regulators.” Further from the New York Times: “Mr. Greenberg, who was removed by AIG’s board last march, remains under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Justice department and faces a lawsuit by the New York Attorney General, Eliot Spitzer.”

After invoking his Fifth Amendment right to avoid testifying, Greenberg settled with the SEC for $15 million. And a federal judge, in a written opinion, found evidence that the conspiracy to deceive investors originated with Greenberg. Even CNBC covered Greenberg’s settlement by saying “Ex-AIG CEO Greenberg settles fraud charges with SEC.”

So Mr. Langone, despite your effort to talk about everything other than the facts of these cases, facts matter. These cases were absolutely correct, important, and went to the heart of the type of corporate fraud and defalcation that very nearly destroyed our economy.

On CNBC, Langone also made some noise about fabrication of evidence: “There was a case recently heard, a court of appeals in New York state, where the judge is allowing the case of a doctor to go forward because the judge says there’s indications that Spitzer and his staff fabricated evidence.”

Baloney, Ken. And I am editing that for a family audience. Best as I can tell, he is referring to a case relating to the prosecution of a dentist for Medicaid fraud—really. What that has to do with Langone, Greenberg or their buddies, or me, is hard to see.

Perhaps most surprising, Langone and his host complained about my past use of language, and claimed that I am a bully. Believe me, I’ve heard this one before. Let me say this. Most folks thought I was tilting at windmills, that I was David vs. their Goliath. And I think the power is much more on their side of the field than it ever was on mine. I guess CNBC and its television personalities have forsaken any effort to seek the truth. They are happy to simply be apologists for Wall Street and corporate corruption—a massive self-perpetuating conflict of interest.

Finally, let’s put the specifics of these cases and Langone, Grasso, and Greenberg aside for a moment. The larger point is that the apologists and deniers are trying to blind us to the massive problem we still have in the arena of corporate fraud. A plutocracy that almost destroyed our economy cannot admit its sins, cannot own up to its own grievous failures.