In a rambling, 17-minute YouTube video called “Swing Fail,” the mom of young children Caleb, Annie, and Hayley Logan films and narrates as they make a casserole at home, then pile into their car to go to the park. Other than the ordinary family antics, nothing much happens—the titular “swing fail” involves Annie lightly skinning her knee—but the video has 9 million views. “Bratayley” is a top YouTube family.

YouTube families, or “family vloggers” as YouTube likes to call them, are huge business, with some 41 million subscribers together among the top channels, which earn millions of dollars. The families post cartoonish videos of everyday activities, from new purchases and sibling pranks to welcoming a new baby. Aside from some snappy editing and occasional soundtracking, the videos are numbingly mundane and unchanging from one family to the next. Two parents and their many kids take trips to Target, cuddle giant teddy bears, perform birthday pranks, build snow forts, bounce in bounce castles, and play around in in big, pastoral American homes. The families are overwhelmingly white but are willing to be “on fleek.”

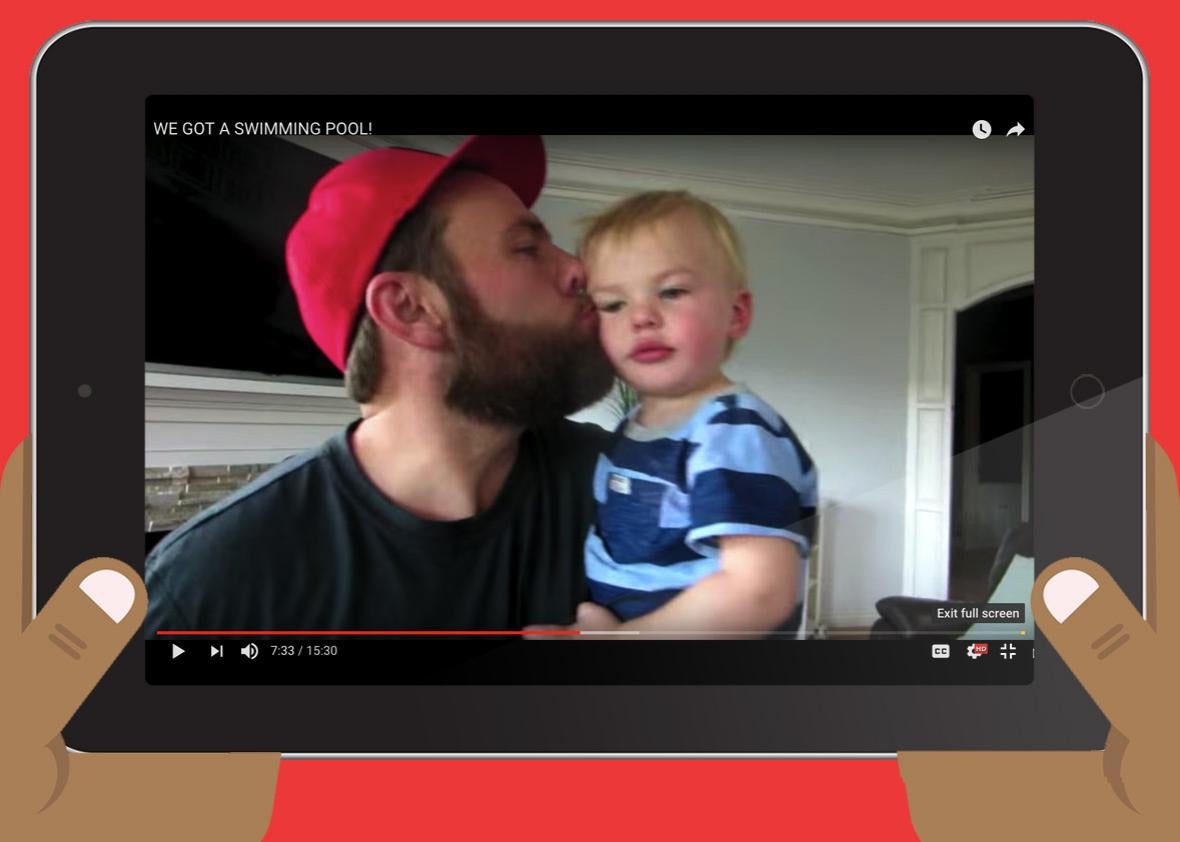

All these families and their content are similar enough that it’s hard for the untrained eye to discern why any particular one has been anointed over others. Parents and children mug for their audience of millions with the same ageless, frenetic gaze. A video of the “Shaytards” (the personalized slur is what dad Shay Carl Butler calls his family) getting a new swimming pool somehow has over 24 million views. Another family, Sam and Nia, made a video of themselves shopping for a pool too—with the same all-caps video title, even—but only got 1 million views. Nice try, Sam and Nia.

Watch enough of these family vloggers and you may find yourself wondering whether there was ever any genuine playfulness in the family’s videos or if they’ve always followed the shrewd choreography of “influencer marketing.” Parents will note that the reality of a house full of kids is not the nonstop funhouse the YouTube families present. A friend who’s a dad of five told me he thinks his kids’ fixation on the Funnel Vision family and their pumpkin-carving, giant gummy adventures suggests dreams of a world where parents don’t have to be so adult. “They’re living this fantasy through the kids on the show,” he said, “the fantasy being the license to be completely silly and have the parents not just support that but be a part of it.”

But fantasies rarely hold up. The swimming pool–loving Shaytards have been on hiatus for some months since Butler, the family patriarch, was caught sending explicit messages and videos of himself to an adult performer online. It’s a little jarring to go from “SASSY FASHION SHOW!” (3.1 million views) to “Letting a Dream Die,” made by Butler’s tearful wife, Colette (2.7 million views). In 2015 Caleb Logan of Bratayley fame died of a heart condition at 13, and a garish media circus followed—audiences were not accustomed to giving the family privacy.

The Bratayley online store now sells Bratayley-branded water bottles, leotards, and fidget spinners emblazoned with “Celebrate Life.” With millions in revenue on the table, it’s hard to imagine all parties keeping kids’ best interests in front. In a recent piece on the “dark side” of family YouTube, Rachel Dunphy tells the upsetting story of Allie, an entrepreneurial 13-year-old toy reviewer whose mother’s hunger for success wrung the child out. Perhaps as a result of James Bridle’s widely-shared article on the bizarre, violent algorithmic content found in the dank annals of kids YouTube, the company has been attempting to crack down on video content it thinks is exploitive of children or harmful to them. BuzzFeed’s damning reportage recently showed how extensive and weird the gray area has been until now—kids tied up, pretending to wet themselves, or playing with diapers.

Can kids even truly consent to this use of their image? For that matter, what does it mean when a parent is, essentially, a child’s employer? In the case of “DaddyofFive,” two parents played tricks on their children and lied to them in order to film and monetize their distress as comedy—and ultimately lost custody of those children, facing charges of child neglect. But even in cases where children in happy homes seem to be willing participants, you wonder how kids like Chase, Mike, and Lexi of the Funnel Vision family might feel one day about this obsessive documentation of their childhoods or the inarguable fact that in the influencer economy, mom and dad are bosses and their kids are the stunt cast. In a video bemoaning the effect YouTube’s kid-friendly content changes may have on the family’s livelihood, “Sky Dad” of the Funnel Vision family commands his son to laugh. The child does so instantly.

It feels worse, somehow, than reality TV, where the premises follow familiar rules and it’s mostly only eager adults being humiliated on cue. These families enact warmth and spontaneity while serving up their children in response to analytics and demand. Meanwhile, most of the kids (and probably many adults) that watch lack the circumspection to see these family performances for what they are—calculated grabs for advertising revenue, dipped in the crunchy candy shell of white suburban ideals.

Even as YouTube has become a major entertainment network in its own right, the organic fiction promised by the “you” in its name still lingers, helped along by the purposeful shaky-cams and staged “oops” moments families craft to make their videos feel raw and homemade. This kind of thing is, of course, happening all over the web—a malleable veracity around everything we access and consume. Fake YouTube families are the perfect entertainment fiction for an era in which young people think collectively edited Wikipedia is untrustworthy but tweets or Facebook posts are plausible because they’re individual accounts.

When anything can be “fake news,” it’s tempting to assume that the solution is “media literacy”—teaching young people to look into the provenance of the content they encounter online. But what if the content appears to come from a kid just like them or a loving parent just like theirs—but who seems to be having so much more fun? It’s hard enough to impress upon literate adults that the reality selected for us by internet algorithms is incomplete. The kids are going to have it rough, whether or not their parents make them jump in ball pits on the internet for money.