Screen Time is Slate’s pop-up blog about children’s TV, everywhere kids see it.

This season’s most-acclaimed film, Lady Bird, checks off all the standard entries on a high school movie to-do list. As the title character, Saoirse Ronan shops for prom dresses, applies to college, falls for an arrogant loner, and clashes with her mom—like any other teen movie heroine. But she has at least one thing nearly every other protagonist in the genre lacks: pimples.

Ronan told Vanity Fair that her skin “wasn’t great” during production. When the Lady Bird makeup artist asked Ronan, then 22, if she’d be OK letting her acne show, she agreed. “I thought it was a really good opportunity to let a teenager’s face in a movie actually look like a teenager’s face in real life,” Ronan said. Writer-director Greta Gerwig claims she was tired of seeing teenage girls in movies with “perfect skin and perfect hair, even if they’re supposed to be awkward,” when the average teenage experience is beset by zits and French braids.

The impossible beauty of teen characters in film and TV is partially attributable to Hollywood’s aspirational human palette, which represents a limited range of acceptable physical characteristics. But it’s also an inevitable upshot of an industry that routinely casts actors in their mid-20s or even their 30s as bumbling pubescents. In a culture as shaped by media imagery as ours, the systemic misrepresentation of an entire age group has real consequences for how adults conceive of typical adolescence, and how teens measure themselves against it.

With a few exceptions like Saved by the Bell and Skins, which were deliberately cast with actors around the same ages as their characters, the best-known on-screen teenagers have been brought to life by far older bodies. Carrie starred 26-year-old Sissy Spacek as a high-schooler a decade younger. Ingrid Bergman was well into her 30s when she played the teenage lead in 1948’s Joan of Arc. In Grease, a timeless archetype of high school dramedy released in 1978, the lead roles were played by a 24-year-old John Travolta, a 29-year-old Olivia Newton-John, and a 34-year-old Stockard Channing. With the exception of then-17-year-old Mischa Barton, the chief clique of The O.C. was populated by actors in their early and mid-20s. Mean Girls featured a 25-year-old Rachel McAdams as a high school bully; Amy Poehler, who played her mother, is just seven years older.

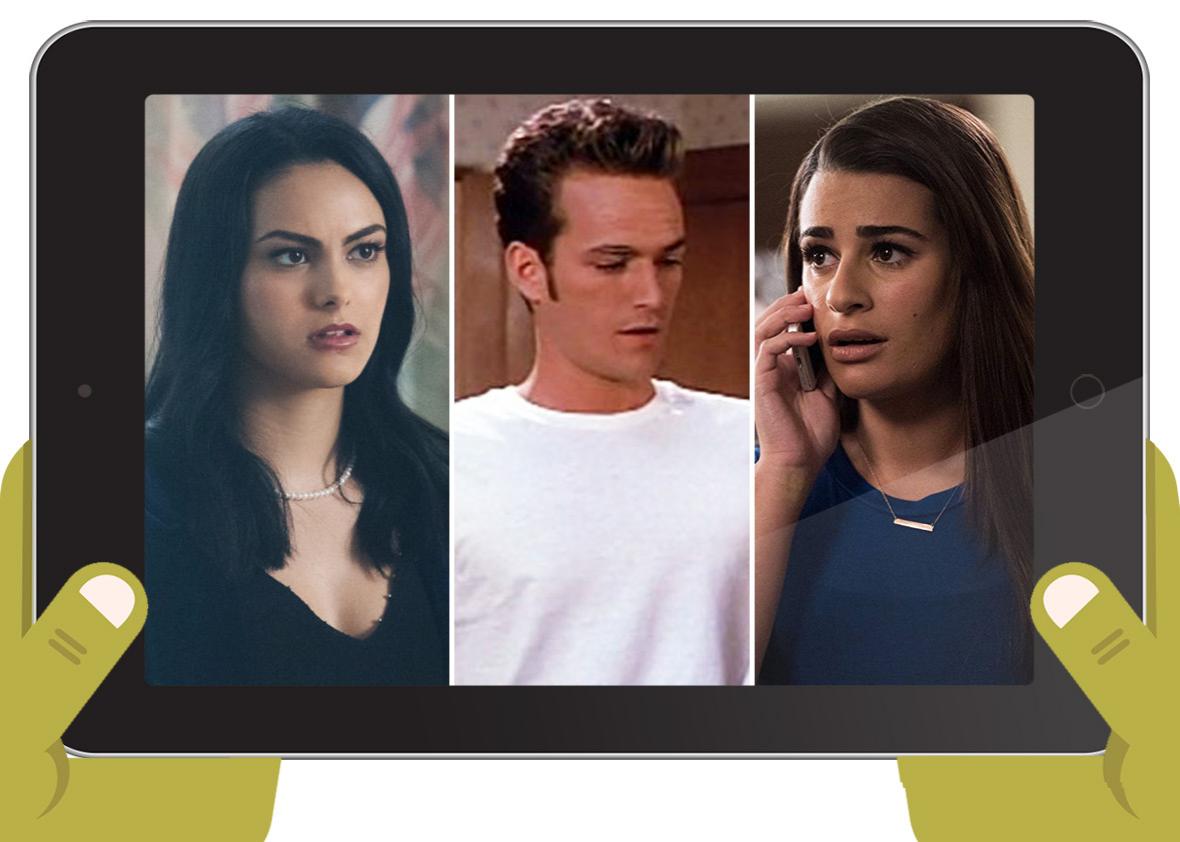

These aren’t isolated examples. This spring, Broadly calculated the respective age differences between the characters and actors in 11 popular films and TV shows set during high school, including The Breakfast Club, Clueless, and this year’s Riverdale. Teens playing teens make up a tiny minority of those in the study, for whom the average age gap ranged from 3.7 years (Gossip Girl) to 8.25 years (Buffy the Vampire Slayer). The cast members of Glee (average age gap: 8 years) were almost all past college age when they started as high school sophomores on the show, prompting creator Ryan Murphy to graduate the characters in real time, after the third season. “There’s nothing more depressing than a high schooler with a bald spot,” he said when he announced the plan.

Bald spots are not the issue for teenaged viewers, though. It’s the more conventionally sexualized parts of adult bodies—breasts, hips, upper body musculature—that can give teenagers unrealistic points of reference for their own development. Beth Daniels, a developmental psychology professor at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, remembers that some teen shows used to feature actors who, while still older than the characters they were playing, could actually pass for high schoolers—like baby-faced Alexis Bledel, who was 19 when Gilmore Girls premiered. “In contemporary teen shows today, they have actors who don’t even physically resemble teenagers,” Daniels said in a phone interview. Their faces are framed by high-relief Adam’s apples and square, stubbly jaws; their smooth-skinned, un-stretchmarked bodies have no trouble filling out adult-size lingerie. “So now the expectation, or the standard, is way out of line with actual teen bodies, and the possibility for body dissatisfaction jumps up.”

There are several reasons why casting directors tend to choose legal adults to play teenagers on screen. First on the list is labor law. Minors can only work limited hours and require additional accommodations for schooling and break time, while adult actors can spend longer, more efficient days on set. Adolescence itself, characterized by unpredictable changes, is itself an obstacle. “The lived reality of puberty does not play well on screen,” said Rebecca Feasey, who teaches gender, media, and film studies at Bath Spa University in the U.K. “This is not about aesthetics, but rather about continuity—continuity which would be challenged by developing bodies and deepening voices.”

Older actors can also perform the kinds of sexual situations that provide much of the drama of contemporary teen narratives without raising ethical concerns. Pacey Witter was only 15 when he started sleeping with his high school teacher on Dawson’s Creek, but Joshua Jackson, at 19, was above the age of consent. In other cases, age gaps buttress a show’s believability. On Gossip Girl, the very adult sex life of 16-year-old Chuck Bass seems more plausible when portrayed by Ed Westwick, who was a very self-possessed 20 when the show debuted.

Panic over child exploitation has often accompanied films that cast young actors as sexualized characters their own age. When a 12-year-old Brooke Shields played a sex-trafficked child in 1978’s Pretty Baby, child welfare organizations “threatened to take the child actress out of her mother’s custody,” writes Kristen Hatch, a University of California, Irvine, film and media studies professor, in her essay “Fille Fatale: Regulating Images of Adolescent Girls, 1962-1996.” It would make sense, then, for producers to cast adults in productions that depict young teens engaging in sexual activity, rather than navigate the complex moral and PR dilemmas that arise around child performers. But the upshot is a pop culture canon in which most teenagers—those youths with squeaky voices, underdeveloped prefrontal cortices, and still-growing bodies—are played by people who look and sound far older.

Early this year, BuzzFeed’s Erin Chack pointed out the ludicrousness wrought by this discrepancy, comically juxtaposing stills from TV shows and movies about teenagers with photos of her and her friends as actual teenagers. Chack’s exercise takes on new meaning when viewed through the lens of the recent #MeAt14 hashtag, under which people tweeted photos of themselves at the age of one of Roy Moore’s accusers when the GOP Senate candidate allegedly molested her. (Moore claims that the several women who’ve said he sexually assaulted or dated them when they were teenagers and he was an adult are all lying.) If you don’t spend a lot of time around young teenagers, you may not have an easily recallable image of what a 14-year-old looks like to remind you of how unadult ninth-graders are—and thus how unfathomable it would be for a man in his 30s to have anything approaching a consensual sexual relationship with one. The #MeAt14 hashtag also encouraged survivors of sexual violence to tweet photos of themselves at the age their abuse began, reminding observers that the defenses Moore’s supporters offered—that his alleged relationships with teen girls were consensual, innocent, and appropriate—were absurd. Romantic affairs between high school girls and assistant district attorneys old enough be their fathers are not, and should not, be the norm.

The immature realities of adolescence can be hard to remember, especially when the high school stories we watch on TV involve 25-year-olds acting out sex dramas foreign to the average teenager. Daniels says today’s teen shows, most of which include sexually active characters, misrepresent the reality that in the U.S., only 41.2 percent of high school students report having ever had sex, and just 11.5 percent have had sex with four or more partners. “It’s really different than even in the ‘90s,” Daniels told me. “If you think back to the first run of 90210, the majority of the characters, while they were in high school, were not having sex. … It was still a really big, long, drawn-out process as to whether Brenda was going to sleep with Dylan. And yet, today, we see shows where it seems like the characters are not only sexually active, but having multiple partners, and that’s incredibly uncommon for teenagers.” Shannen Doherty was 19 when she played Brenda, a 16-year-old, in the first season of Beverly Hills 90210 in 1990. As fellow high schooler Dylan, Luke Perry was 23.

While sex as a standard backdrop rather than a scandalous plot point is a relatively new feature of on-screen narratives, Hollywood has fetishized young girls as sexually ready adults, and made adult women into innocent girls, since nearly the birth of cinema. In 1919’s Broken Blossoms, Lillian Gish, then in her mid-20s, played a 12-year-old girl who must decide how she will escape her physically abusive father: either by engaging in sex work or by attracting another man to protect her. Later decades found films such as 1940’s It’s a Date, 1945’s Mildred Pierce, and 1964’s Where Has Love Gone—the last of which featured 19-year-old Joey Heatherton as a 14-year-old girl—trading on the trope of a daughter competing with her mother for the same adult man, in line with then-popular Freudian ideas of sexual development.

Casting adults as sexy, grown-up “teenagers” comes naturally in a culture with dual fixations on youth and the objectification of women. So does the reverse-but-related practice of using the looks of girls deemed unusually mature against them when they’re sexually abused. When Roman Polanski pleaded guilty to unlawful sex with a 13-year-old girl in 1977, his probation officer submitted a report that said the survivor “was not only physically mature, but willing.” The judge in the case, Laurence J. Rittenband, qualified his admonishment of Polanski with the assertion that the girl “looks older than her years,” as if her body shape or proclivity for makeup made her a likelier target, as if poor Polanski simply could never have known she was way underage. Thirteen-year-olds that look 20 are still 13, and women shouldn’t need to tweet a photo of themselves in braces to prove that abuse they suffered as teenagers was wrong.

Notably, Kristen Hatch casts doubt on the idea that consuming portrayals of high-schoolers by adult actors could warp viewers’ understanding of teenage immaturity. “Puberty is a time when things are not stable, so everything’s amorphous and it’s kind of hard to say what, precisely, it looks like,” she told me. All on-screen fiction demands some suspension of disbelief—maybe there’s not such a big difference between making teenagers look old enough to run for Congress and making college quads look like nonstop ultimate Frisbee and flip-cup tournaments. Or, for that matter, casting young actresses as middle-aged moms. “There is routinely a very small age gap between on-screen parents and their children which is biologically unrealistic and potentially implausible,” Rebecca Feasey said. “The irony, of course, is that while we are happy to accept twentysomething performers playing teenagers, we are keen for thirtysomething actors to take on the role of fortysomething parents.” For women in Hollywood, once adolescence is over, menopause is just spitting distance away.