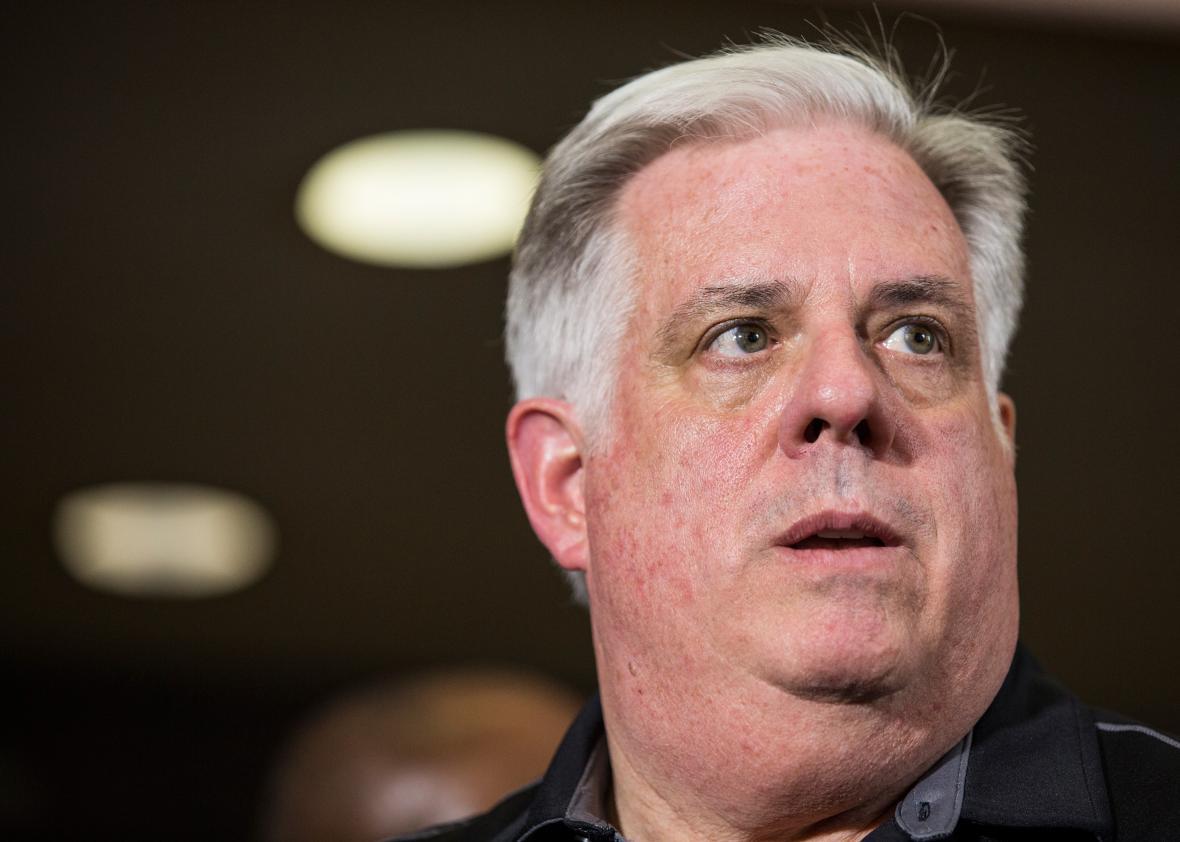

Even as Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan is joining many of his Republican colleagues in opposing additional refugee resettlements in his state, schools in Prince George’s County, Maryland—just over the Washington, D.C., line—are taking steps to do a better job of educating (and graduating) the immigrant and refugee kids who are already here. A Baltimore Sun story over the weekend looked at the recent opening of two innovative high schools designed to serve the county’s 20,000-students-and-counting population of English-language learners.

It’s common for schools to place immigrants—even those who arrived in the U.S. during adolescence—in regular classes, regardless of their previous educational level or competency in English. According to the Sun story:

Most schools put newcomers into high school science, math, history and English classes with their American peers within months of their arrival in the United States. That could mean a 15-year-old who reads at a second-grade level is enrolled in a high school biology class. Some learn quickly and catch up, but others have difficulty and drop out.

A great many fall into this latter category in Maryland, where “slightly more than half of the students who are learning English as a second language are graduating from high school in four years, compared to 87 percent for all students.”

The two new schools in Prince George’s County represent a formal attempt to adapt education to the unique needs of recently arrived students, some of whom have had very little formal schooling; some of whom have fled violence and trauma; many of whom are nothing close to fluent in English.

The Prince George’s schools, which in their inaugural year have enrolled students from more than 30 countries, are the work of the Internationals Network fo Public Schools, a nonprofit with the goal of ensuring that “all recent immigrant students have access to a quality high school education that prepares them for college, career and full participation in democratic society, thereby opening doors to the American Dream.”* With cash from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and a push from the CASA de Maryland, an immigrant advocacy group, the two schools opened on existing high-school campuses in the county.

The new Maryland schools are small, with coursework tailored to each student’s skill level, a version of what’s known as competency-based learning, or personalized learning, a type of pedagogy geared toward “enabling students to master skills at their own pace,” according to the U.S. Department of Education, that’s gaining traction in U.S. schools (and not just among immigrant populations). The Sun describes how these principles play out in the international schools:

So students are given content at whatever grade level they are able to understand it. If they can’t grasp the ideas in English, then they can learn some of the concepts in their native language. Teachers must meld learning the language with learning the class material.

The Internationals Network has 22 schools in New York City, the Bay Area, Northern Virginia, Washington, D.C., and now Maryland. These schoolroom initiatives are a particularly heartening contrast to all the ugly debates over immigration and refugees currently roiling the political sphere.

*Correction, Dec. 1, 2015: This post originally misidentified the Internationals Network for Public Schools as the Internationals Network of Public Schools.