In the final days of debates over the Senate’s bill to replace No Child Left Behind, which passed with unusual bipartisan support on Thursday, various amendments got offered up and obliterated at lightning speed. Among the more unfortunate casualties was Sen. Al Franken’s Student Non-Discrimination Act, which proposed extending federal protections against bullying to LGBT students. Other amendments were adopted in extremely watered-down form.

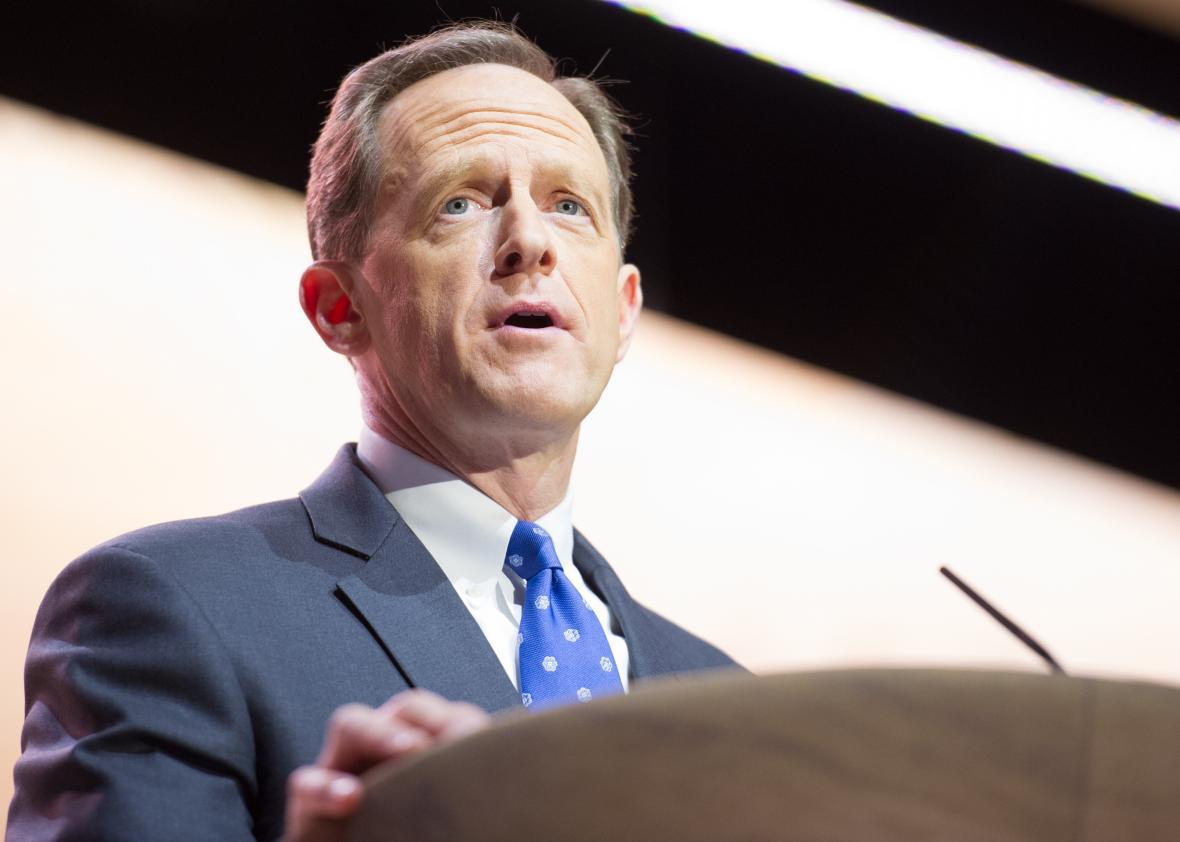

One of the weakened amendments was Sen. Pat Toomey’s Protecting Students From Sexual and Violent Predators Act, which, as originally written, would have required any school that receives federal funding to submit its employees and contractors, regardless of tenure, to periodic background checks through four major state and federal registries. Sounds good, right? But the proposal, co-sponsored by Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, met with only slightly more success than the two senators’ 2013 push to tighten the system of background checks for gun buyers in the aftermath of Sandy Hook.

I glommed onto the background-check provision for the simple reason that I myself have just barely survived the onerous process of getting approved to volunteer in my daughter’s preschool class for three hours a month next year. It was, to put it mildly, a huge pain in the ass. I had to fill out a Child Protection Registry request, on which I listed all my addresses for the past 18 years. After getting that form notarized, I had to schlep downtown to the police headquarters and fill out more paperwork for a criminal background check, and after that I had to get fingerprinted by an FBI mobile unit—all this, just to provide a monthly snack to a handful of 3-year-olds.

I was loudly annoyed by the hassle, but I understood its underlying purpose; I suppose anyone with unsupervised access to my children should submit to the same. But Toomey’s proposal—and the widespread resistance that it met—shows how complex background checks are.

Obviously, no one want wants child predators in the classroom, and all 50 states currently have teacher background check laws on the books. Forty-three states require background checks for nonteaching employees like bus drivers and cafeteria workers. But big loopholes exist. Not all background checks are nearly as thorough as the insane, multiday ceremony I had to navigate here in the District of Columbia. Many only apply to new hires and are never updated, which Toomey says helps to explain why “459 teachers and other school employees nationwide were arrested for sexual misconduct with children” last year.

In his unsuccessful efforts to wedge this bill into other legislation in the past, Toomey has met with opposition from across the political spectrum. Many Republicans thought it represented an untoward federal intrusion into the hiring process; when debating it in March, Sen. Lamar Alexander called it the “most extensive federal takeover of local school personnel decisions in our country’s history.” Alexander proposed a measure that would let the states choose which registries to use for the checks—so pretty much sticking to the status quo.

Teachers unions opposed Toomey’s federally mandated background checks (one of Campbell Brown’s all-time favorite anti-union talking points, incidentally) because they could interfere with district contracts with teachers and set a bad precedent for collective bargaining. Progressive politicians like Rep. Keith Ellison have just as forcefully come out against Toomey’s amendment, since the background check registries he wants to mandate that schools use, particularly the FBI’s fingerprinting system, are often incomplete or inaccurate. Ditto for civil rights groups that believe Toomey’s bill—which bars people who’ve been convicted of certain crimes (some having nothing to do with sex) from getting jobs in schools—would prevent people from overcoming their criminal pasts; a long-ago conviction for, say, marijuana possession should not be a deal-breaker. As a corrective to these concerns, in an earlier bill Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse proposed a more limited background-check system, supported by the unions, that goes into more detail about which crimes should bar employment.

In the end, background checks got chucked altogether, and the only part of Toomey’s bill that survived would ban federal money going to schools that engage in the repulsive practice known as “passing the trash”—i.e., knowingly recommending an employee dismissed for sexual misconduct with a minor to another district or state. Well, yes, I suppose we can all get behind that one.