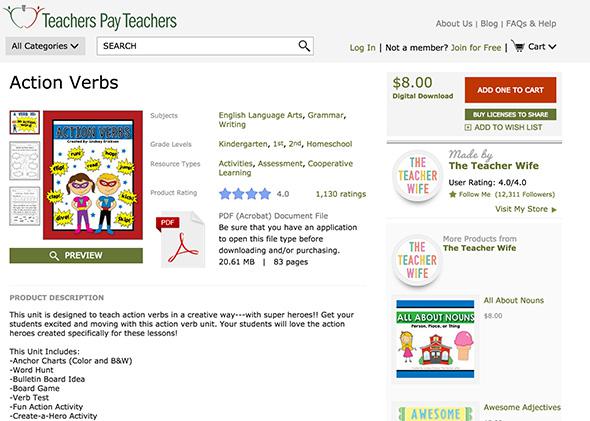

Seven years ago, when Erica Bohrer, a first-grade teacher from Long Island, New York, started selling her lesson plans on the website Teachers Pay Teachers, she just wanted to make a few extra bucks here and there. Items on the site, a kind of Etsy for educators, go for an average of $3.50.

Good decision. To date, Bohrer’s sample classroom decorations, reading comprehension cards, and lesson plans have earned her nearly $450,000—and she now makes more money each year on the site than as a full-time classroom teacher.

The exploding popularity of Teachers Pay Teachers, which has paid out $150 million to its sellers since 2006, is at least partially attributable to the desperation scores of teachers feel as they try to devise lesson plans and teaching strategies that are aligned with the Common Core, the educational-standards initiative that’s been adopted by most states since 2010.

The popularity of the Teachers Pay Teachers speaks to something else, too: When it comes to their craft, teachers trust each other most. More than experts. And far more than textbook publishers, who have been slow to produce enough materials that are in sync with the standards. In a national survey by the Education Week Research Center, 87 percent of teachers polled said they trusted other teachers’ claims about whether curriculum materials are aligned with the Common Core. By contrast, slightly less than two-thirds said they trusted independent panels of experts. And only 38 percent said they trusted curriculum providers and publishers. For teachers, the main kind of expertise that matters is hands-on. And one of the most widespread yet understated benefits of the Common Core may be the way it has motivated and empowered teachers across the country to, well, talk to each other more.

Teachers Pay Teachers has been around since 2006, but its active users and sellers have both doubled in the past two years to approximately 3 million and 50,000, respectively. Over the same timespan, the number of products for sale jumped from 750,000 to 1.5 million. There are similar sites out there, including Teacher’s Notebook, BetterLesson.com, and ShareMyLesson.com (which was developed by the American Federation of Teachers union). They vary in terms of whether they charge for content or focus exclusively on the Common Core.

On Teachers Pay Teachers, a guide that explains how to accommodate a classroom for kids with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder goes for $2.50. A packet on how to teach parents about guided reading sells for $3.50. Not surprisingly, Common Core workbooks and ready-to-use lesson plans are consistently strong sellers. When the United Federation of Teachers surveyed New York City public school teachers in late 2013, about half of them said they did not have the curricula and materials needed to teach to the Common Core standards.

One of Bohrer’s most popular items is a 125-page packet that shows teachers how to use picture books to teach letter-writing. Each lesson or activity includes the relevant Common Core standards. For example, asking children to write letters to the tooth fairy can help teachers work toward the kindergarten writing standard that students be able to use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to compose “explanatory texts.” The packet costs $10. Another popular item is a sample “evidence binder” teachers can use to compile examples of their “effectiveness” (something many teacher evaluation systems now require). “I just put a little disclosure in there that says ‘I am not responsible for your score,’” Bohrer says.

Karen Jones, an elementary school teacher from Buffalo, New York, also earns more from the site than her teaching job. She puts her children to bed each night at 8 p.m. and then spends the next few hours creating new products, responding to her customers, and promoting her work on social media. Jones discovered some of her peers were struggling to track student progress with the Common Core English standards over the course of a year, so she created a 300-page document that helps teachers do just that. The work took her more than six months, and the packet sells for $27 (currently marked down from $31.50). Five teacher reviewers on the site called Jones a “lifesaver.”

Bohrer says in an email that Teachers Pay Teachers is thriving because buyers know “they are getting something that has been tested out on real kids.” The textbook industry has indeed struggled to respond quickly to the standards. Several states and organizations have been monitoring the alignment of curriculum materials from major textbook publishers with the Common Core. They’ve reported some dismal results: One recent report, for instance, concluded that 17 of 20 math curricula were out of sync with the standards despite claims to the contrary.

But some experts point out that many teachers are not trained or experienced curriculum developers. And they worry about educators relying too heavily on already overburdened teacher-freelancers to create thousands of new curriculum materials aligned with the Common Core.

The nonprofit Center on Education Policy has reported that in about two-thirds of districts using Common Core, teachers are developing their own materials aligned with the standards. That’s not only because they trust each other more than textbook publishers, says Diane Rentner, the center’s deputy director. Particularly in the standards’ early days, “there was nothing else out there.”

When teachers play lead roles in developing these materials, it helps them more deeply engage with the standards, Rentner said. “But if they don’t know how to develop curriculum, it’s a bit of a problem.”

And most everyone agrees: Some teachers know how to develop curriculum materials or can learn quickly. And many, many others don’t—or can’t. Though Bohrer has years of experience creating her own curriculum materials and leading professional development workshops in her district, others may be accustomed to following a comparatively scripted curriculum laid out for them in considerable detail. And there’s nothing stopping nonteachers—with no classroom experience or even teaching certifications—from selling items on the sites.

It can be hard for even the best teachers to juggle creating curriculum materials with their day jobs. Bohrer has considered leaving teaching to focus on her Teachers Pay Teachers store. But she’s not quite ready to give up the profession just yet. Still, she spends so much of her free time online that she has trouble finding time to cook, work out, or date.

Bohrer admits the site has consumed her life. But it’s also brought her more financial security and brought her into contact with colleagues from all over the world. Six-year-olds don’t thank her for her effort after class every day, but many of the educators who download her products do.

“I feel like I have a purpose,” she says.

Madeleine Cummings is a fellow for the Teacher Project, an education reporting initiative at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism dedicated to covering the issues facing America’s teachers.