When Shane was in elementary school, he could go months without advancing a reading level. And even though his mom, Carrie Shepherd, considered herself an involved parent, she sometimes wouldn’t know that her son, who has dyslexia, had stalled until she saw Shane’s latest report card. “You wonder, ‘What could I as a parent have done had I known?’ ” she says.

Since Shane started middle school this fall, however, that hasn’t been a problem. Carrie doesn’t have to wait until the end of each quarter for Shane’s teachers to reduce his performance in each class to a letter grade. Instead, she simply logs on to an online grading system that’s updated on a daily basis by teachers at Brooklyn’s M.S. 442, known as Carroll Gardens School for Innovation. Online, Shepherd can see how Shane is progressing on dozens of different skills, from becoming a stronger reader and writer to learning to multiply and divide fractions. “If he doesn’t exceed or meet the standards, I say, ‘Well Shane, what can we do?’ ” Shepherd says.

Last year, M.S. 442 decided to throw out the old way of reporting student results, adopting an increasingly popular model known as standards-based grading. This approach looks a bit different in each place it’s used, but at M.S. 442 there’s a continuously updated online grade book where, over the course of a school year, students are rated on more than 70 different skills, such as the ability to write persuasively, determine the main idea of a passage, or multiply fractions. (All of them are tied to specific Common Core standards but translated into more straightforward language.) Progress is color-coded: Green means a student has mastered a skill, yellow means a student is on track, and red means a student is just getting started or still has a ways to go before grasping the material. Students need to demonstrate proficiency three separate times—through homework, on a quiz, or through some other means—to be considered proficient. A student who ends the year with all, or mostly all, reds likely won’t progress to the next grade.

Supporters hope standards-based grading will transform how schools help their weakest students by highlighting deficiencies on a more regular basis to parents and teachers alike. But that can only happen if the new systems are thoughtfully executed and carefully explained. And since an increasing number of schools and districts began using this method over the last few years, some have faced a steep hurdle in reaching out to low-income and disconnected parents who are less likely to have the computer savvy and time to scrutinize the sometimes complex online reports—to say nothing of even having reliable Internet access. But, if done well, standards-based grading has the potential to make education more equitable by helping teachers more fully identify and communicate individual students’ weaknesses and strengths.

In recent years, some form of standards-based grading has been adopted statewide in Oregon, Kansas, and Hawaii. California is becoming a major player—San Diego, Sacramento, and San Francisco all use the model—as are parts of Arizona and Connecticut. The shift is fueled partly by No Child Left Behind and Common Core, major policies that motivate teachers to more closely track students’ performance on individual skills—partly because their own fates (as well as their students’ and schools’) are increasingly tied to standardized test-score results.

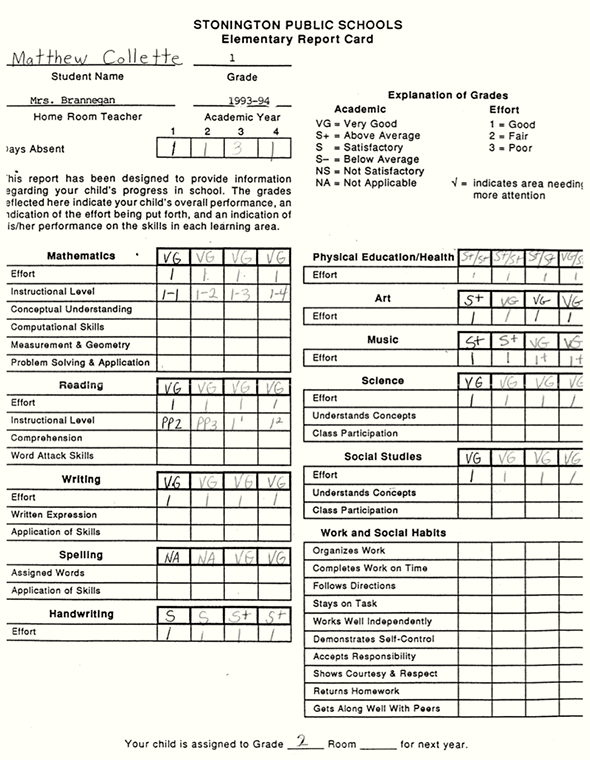

Courtesy Matt Collette

Though most us grew up with letter grades, standards-based grading isn’t an altogether new concept. Some schools have long rated students by various standards. (My own elementary school report cards, from the early 1990s, broke down performance on specific skills and included separate scores for effort.) The recent efforts take standards-based grading to a new extreme, however, by doing away with traditional letter grades altogether in some cases, and mandating the approach across entire states in others.

The model is more common in lower grades than in high schools, largely because districts are still rolling out the new systems. For colleges, this style of secondary school grading could eventually provide more information about potential students. A 2014 survey of colleges by the Illinois Board of Education found that all its public universities and four-fifths of private universities supported standards-based grades.

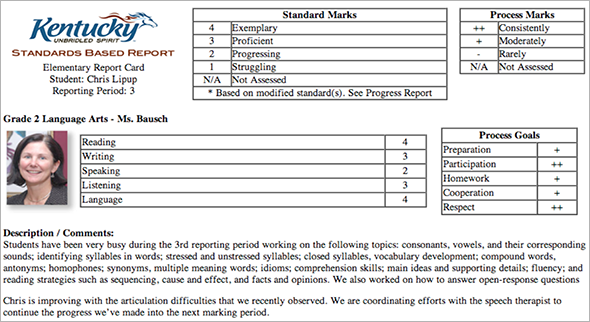

When Kentucky adopted standards-based grading statewide about three years ago, the first months were rocky. For the first two marking periods of that year, Kentucky schools sent home two report cards: one that used the old summary letter grades and another that showed how students performed on a number of standards. The new report card rated students on up to six different academic skills per class, provided a short written evaluation from the teacher, and included separate marks in areas like preparation, participation, and respect. But teachers, who were trained more on the mechanics of the new system than the idea that it’s not just extra work but can be used to better communicate with parents and help individualize instruction), didn’t immediately embrace this new idea.

Courtesy Thomas Guskey/University of Kentucky

“We didn’t teach the philosophy early on,” says Jamie Kellam, a teacher and the director of secondary education for the Grant County Board of Education in rural Williamstown, Kentucky. So in the face of resistance and confusion, administrators paused the rollout, regrouped, and built a task force that included teachers who understood the new system. That group wrote a “user manual” that better explained the thinking behind the change.

After two marking periods of sending home both report cards, school officials surveyed parents on which version they preferred; they overwhelmingly selected the new report cards. “They became our strongest supporters because it gave them more and better information,” says Thomas Guskey, a professor of educational psychology at the University of Kentucky and a leading advocate for standards-based grading. “When parents have the experience of this they can see the value of this.” Kentucky is among the first states to adopt this model for all schools; the rollout began at elementary and middle schools, with high schools are in the process of deploying the new system.

Indeed, the new report cards have the potential to help teachers and parents come together to help the most struggling students improve. At M.S. 442, standards-based grading has helped change how classes are taught, with an eye toward better reaching the lowest performers—and letting the strongest students forge on ahead. Rarely do teachers gather the whole class together for a single lesson anymore; instead they work one-on-one or in small groups.

Photo by Matt Collette

Eighth graders in Jared Sutton’s M.S. 442 math class spend most of the period on laptops. Sutton and his co-teacher, Ed Oliva, move around the room, working with individual or small clusters of kids. The day I visited the class, most students were working on basic elements of scientific notation, though some were still reviewing more foundational skills, like multiplying and dividing exponents, while others had already advanced to the next lesson. This kind of teaching is made easier, Sutton and Oliva say, in large part because of their day-to-day tracking of student performance, which they’re constantly discussing with each other and their students. “For us, it’s a great way to organize our thinking,” Sutton says.

The information can be used in a similar way by parents. When Shane Shepherd gets home from school each day, he and his mom log onto the online grading program, called Engrade, and scrutinize the skills he has and hasn’t mastered. Then they make a plan together: more practice after school, more reading before bed, more conversations with teachers. One recent week, they focused more on writing, an area where the daily check-ups showed Shane was struggling.

But not all parents have the time, or knowledge, to grasp the new report cards. And most only have experience with traditional letter grades, imperfect as they may be. Deanna Sinito, M.S. 442’s principal, says getting her Brooklyn parents to understand what the new grades mean has been the hardest part of the process. And, she acknowledges, that’s partly on the school: Right now parents either need to log onto the online system or pore over a printout that lists progress on every single standard, a massive document, issued three times a year, that can feel overwhelming to some parents. (Coming soon: a shorter, one-page progress report that summarizes the much more detailed information available online.)

Making this kind of grading more accessible is important because while standards-based grades can be incredibly informative, they’re not always intuitive. Take, for instance, a student deemed proficient on 50 percent of learning goals midway through the school year. “That’s not failing, but 50 percent on a typical zero to 100 scale would be failing,” Sinito says. “So there’s a learning curve there explaining that to families.” Sinito says she has staff on hand at every school event to provide one-on-one instruction in the new system. But, of course, not all parents come to the events.

In Kentucky, parents of the highest-performing students have also had gripes. Some are upset that students have the opportunity to retake tests and quizzes as many times as necessary to show they’re proficient, arguing the new policy gives students unfair advantages to get good grades. But advocates of this method say that’s exactly the point: Grades now have less to do with who’s on top and more to do with making sure students actually learn the skills and lessons they need before moving on to the next grade.

“We want students to learn—it doesn’t matter when they learn, as long as it happens in the school year,” says Rebecca Boden, the director of elementary education for the Grant County, Kentucky, Board of Education. “It might happen in November, it might not happen until April.”

In most places, standards-based grades remain a work in progress. And while that would likely net schools an “Incomplete” on a traditional report card, they’d likely fare better with the grade book M.S. 442 has adopted: a couple reds representing work still to do, a lot of yellow showing steady progress, and a few standout patches of green.