In the days since Brendan Eich quit Mozilla, supporters of same-sex marriage have debated the wisdom of using pressure to punish their opponents. Eich, an executive with no known record of antigay bias in the workplace, was forced out for having donated $1,000 to the 2008 campaign for Proposition 8, a ballot measure that said California would recognize marriage only between a man and a woman.

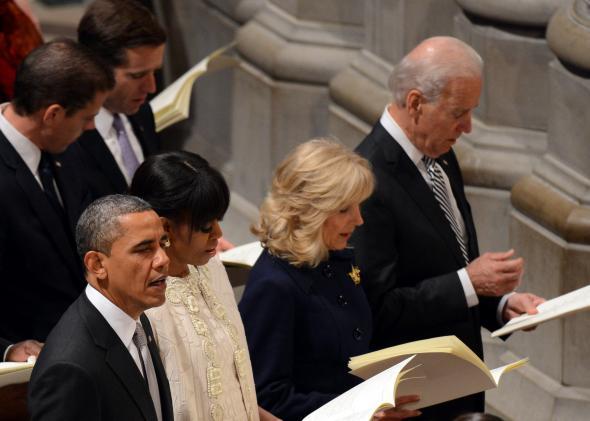

One way to cut through debates like this one is to set aside the rhetoric and look at a real-life case in which progress toward same-sex marriage was achieved. In today’s New York Times Magazine, Jo Becker, the author of Forcing the Spring: Inside the Fight for Marriage Equality, tells such a story. It’s about President Obama and Vice President Biden. The story suggests that pressure is important but that partial acceptance is natural, persuasion is central, and progress is incremental.

Becker’s article, excerpted from her book, ties together several narrative threads. Here are four of them.

1. Biden’s evolution. In an interview, Biden tells Becker several stories about his family’s encounters with homosexuality. The first story, Becker writes, involved

a summer afternoon when he [Biden] was in his 20s. He was sitting on the beach in Delaware with his father and some friends when an older gay couple walked over to say hello. His father, a Realtor, had sold them their apartment in a building nearby. The elder Biden hugged both men and said, “Let me introduce you to my family.” One of the younger Biden’s buddies made a derogatory remark about the couple, and his father’s reaction to it stayed with him all these years. “He says: ‘As soon as they get in the apartment, you go up to the ninth floor. You walk up and knock on the door, and you apologize to them.’ ” When his friend refused, his father said, “Well, goddamn it, you’re not welcome in my house anymore.”

So Biden learned as a young man that it was unacceptable to make derogatory remarks about same-sex couples. Here’s his next story:

Biden then described another day, years later, when his own young son looked up at him quizzically after seeing two men headed off to work kiss each other goodbye on a busy street corner. “I said, ‘They love each other, honey,’ and that was it. So it was never anything that was a struggle in my mind.” The truth was, Biden said, other than being concerned as a Catholic that churches not be forced to perform ceremonies for gay couples, “I didn’t see a problem with it,” and he never had.

So Biden didn’t just believe it was wrong to insult gay people. He affirmed same-sex partnerships, to his own kids, as simple love. At the same time, he favored a religious freedom exception. In 1996, he voted for the Defense of Marriage Act. And when he ran for president in 2008, he endorsed civil unions, not marriage, for same-sex couples.

That’s a complex set of beliefs: Antigay slurs are unacceptable; same-sex love should be affirmed to children; churches shouldn’t have to perform same-sex weddings; states shouldn’t have to recognize other states’ gay marriages; same-sex relationships can be acknowledged as civil unions. Was Biden, at any point along this trajectory, a bigot? It’s hard to see how that’s a fair use of the word.

2. How Biden crossed the marriage line. Becker describes an April 2012 fund-raising event at the home of a same-sex couple. There, Chad Griffin, a gay-rights political operative, “watched the hosts’ two children, ages 5 and 7, press flowers and a note into Biden’s hand.” Griffin decided to ask Biden this question:

When you came in tonight, you met Michael and Sonny and their two beautiful kids. And I wonder if you can just sort of talk in a frank, honest way about your own personal views as it relates to equality, but specifically as it relates to marriage equality.

Biden replied:

I look at those two beautiful kids. I wish everybody could see this. All you got to do is look in the eyes of those kids. And no one can wonder, no one can wonder whether or not they are cared for and nurtured and loved and reinforced. And folks, what’s happening is, everybody is beginning to see it. Things are changing so rapidly, it’s going to become a political liability in the near term for an individual to say, ‘I oppose gay marriage.’ … And my job—our job—is to keep this momentum rolling to the inevitable.

An aide who was in the room tells Becker that “being in that house, seeing that couple with their kids, the switch flipped” for Biden.

That’s how Biden crossed the line. It’s the same way millions of other Americans have crossed it. You accept change a little bit at a time. Eventually, you have too much reassuring experience with gay people to refuse them the last thing you were holding back: the word marriage. What changes your heart isn’t condemnation or intimidation. It’s sympathy, and often love.

3. How Obama approached the public. Like Biden, Obama held a mix of positions. He repealed the military’s antigay employment policy and withdrew the federal government’s defense of DOMA, yet he continued to withhold his endorsement of same-sex marriage. In Becker’s account, however, Obama didn’t really need persuasion on the merits. What he needed was a political path, a way to persuade uneasy voters that same-sex marriage should be legal.

The answer came from Ken Mehlman, the former campaign manager for President George W. Bush and ex-chairman of the Republican National Committee:

He told [Obama adviser David] Plouffe that voters were far more likely to be supportive once they understood that gay couples wanted to marry for the same reason straight people did: It was a matter of love and commitment. Polling indicated that voters would best respond if the issue was framed around shared American values: the country’s fundamental promise of equality; voters’ antipathy toward government intrusion into their private lives; and the religious principle of treating others the way one would like to be treated. Mehlman surveyed 5,000 Republicans and Republican-leaning independents and found that a majority supported some form of legal recognition of gay relationships.

Love, commitment, shared values, religious principles. That’s how you move people. If you condemn anything short of marriage as bigotry, you disrupt this process. In Mehlman’s data, a majority of Republicans and Republican leaners didn’t agree on same-sex marriage. What they agreed on, as a baseline, was “some form of legal recognition of gay relationships.” And that, Mehlman wisely recognized, was a good start.

When Obama came out as a gay-marriage supporter in a May 2012 interview with ABC’s Robin Roberts, he used many of Mehlman’s themes. He added:

Different communities are arriving at different conclusions at different times. And I think that’s a healthy process and a healthy debate. … One of the things that I’d like to see is that a conversation continue in a respectful way. I think it’s important to recognize that folks who feel very strongly that marriage should be defined narrowly as between a man and a woman—many of them are not coming at it from a mean-spirited perspective. They’re coming at it because they care about families. And they have a different understanding, in terms of, you know, what the word “marriage” should mean.

Healthy debate. Respectful conversation. Not mean-spirited.

This message—that a fair-minded, non-bigoted person could oppose same-sex marriage—was what Griffin and David Boies, an attorney fighting Proposition 8, sought to destroy. In January 2013, Becker writes,

Charles J. Cooper, the Washington-based lawyer charged with defending the constitutionality of Proposition 8, filed an opening brief with the Supreme Court, citing the president’s interview with Robin Roberts to argue that bans like Proposition 8 were not motivated by impermissible prejudice. Cooper’s brief quoted Obama as saying that those who opposed same-sex marriage were not coming at it “from a meanspirited perspective,” and it used Obama’s “healthy debate” language to argue that this was a matter for voters and legislatures to decide, not the courts.

According to Becker, at a subsequent White House meeting, Boies warned Obama’s advisers that the president’s failure to insist on a constitutionally guaranteed right to same-sex marriage would “be deeply harmful, signaling that even someone as friendly to gay voters as Obama considered their argument [for such a right] a bridge too far.” Obama had to abandon the middle, lest anyone conclude that one could respect gay people without insisting on federally mandated same-sex marriage.

4. How Obama pitched Kennedy. Becker describes how the administration dealt with the Supreme Court:

[I]f Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, whom everyone presumed would cast the deciding vote in the DOMA case, became convinced that the only way he could strike down DOMA was to adopt a rule of law that would force every state in the nation to allow gay couples to wed, he might get cold feet. “We potentially run the risk of losing him,” Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. told me, reflecting on his concerns at the time. …

Obama wanted to offer Kennedy and the rest of the justices an incremental way to decide the Proposition 8 case that would not force them to overturn bans across the country, a position that he worried the court would find untenable. They arrived at what they referred to as the “eight-state solution.” … The plan was to file a brief with the Supreme Court arguing that in states that recognized same-sex domestic partnerships, it was particularly irrational to ban marriage because doing so could not be said to further any governmental interest.

In the end, the Court confined its decision to California alone. But the eight-state offer illustrated how Supreme Court cases, like other debates, are often won. You don’t demand all or nothing. You try to move your audience a step at a time.

The headline on Becker’s article—“How the President Got to ‘I Do’ on Same-Sex Marriage”—is apt. Our progress toward gay marriage is a courtship, not a war. It takes understanding, respect, persuasion, and patience. Don’t screw it up.