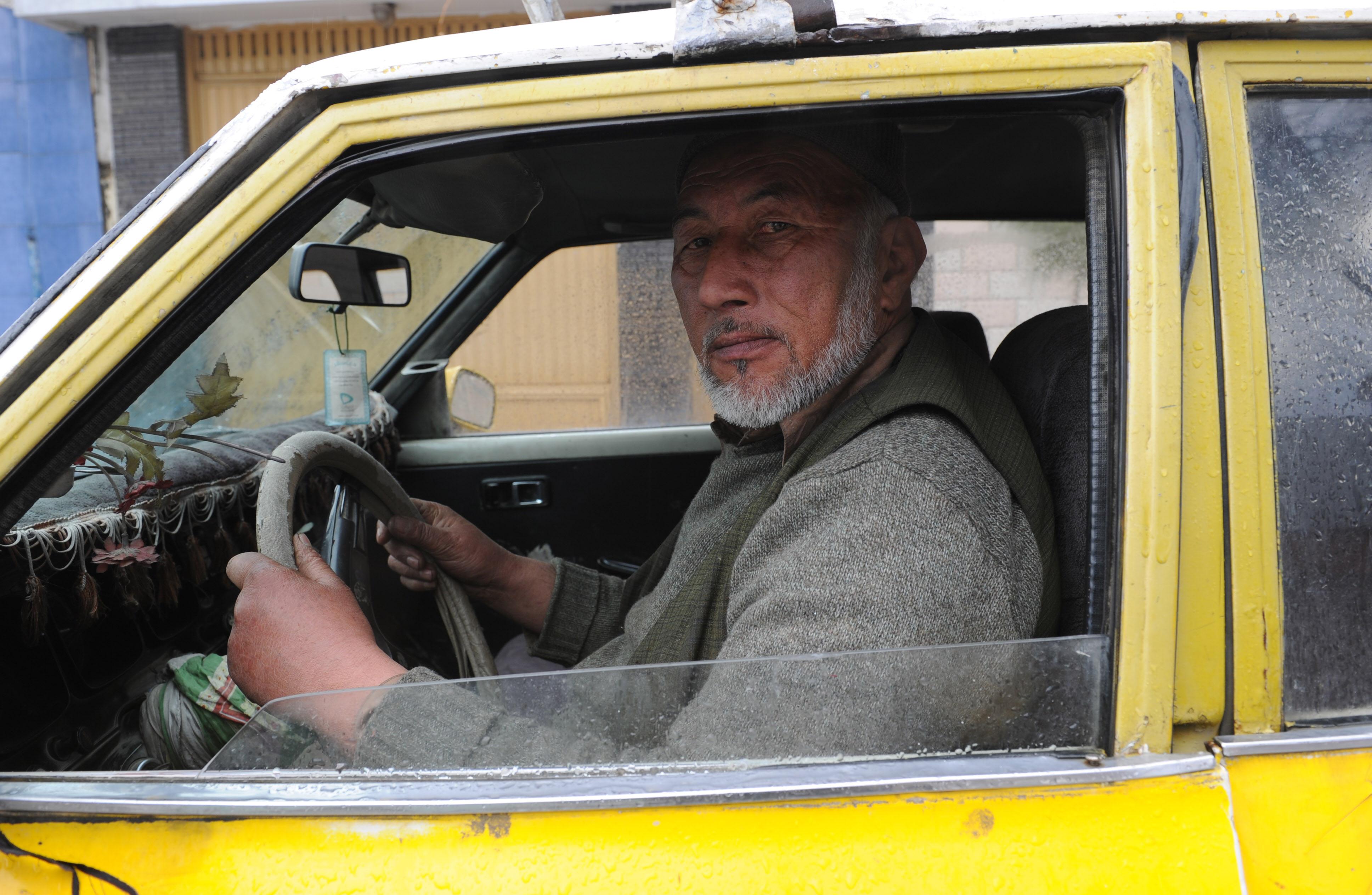

Last week, I wrote about the use of Muslims as bogeymen in the campaign against Arizona’s religious freedom bill. The bill would have shielded businesses from discrimination suits, as long as they were acting on religious beliefs. Everyone understood that the bill would have allowed conservative Christians to refuse services for a gay wedding. But politically, that wasn’t a strong enough argument against it. So opponents raised a different scenario: A Muslim proprietor—typically, a taxi driver—might refuse services to a woman or to a person of a different religion.

Chronologically, the first reference I could find to Muslims in the Arizona fight came from the Anti-Defamation League. I linked to the ADL’s press release about its Jan. 16 letter to state senators, as well as to a committee hearing in which Tracey Stewart, the ADL’s assistant regional director, read from the letter. I quoted Stewart’s testimony (taken verbatim from the letter) that if the bill were to pass, “A Muslim-owned cab company might refuse to drive passengers to a Hindu temple.”

The day after my article appeared, the Arizona chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations demanded an apology from the ADL. A CAIR official alleged: “The introduction of this stereotypical scenario gave way to the narrative that Muslims are in some way serial abusers of ‘religious freedom based denials of service,’ which is completely baseless.”

Technically, the elements of this charge are correct. The scenario was stereotypical. It did give way to an anti-Muslim narrative. And, as far as I can tell, the scenario was introduced by the ADL’s letter and testimony. But the demand for an apology is unwarranted, in my view, because the ADL didn’t put these three elements together. They came together over the course of the Arizona fight, through the intercession of other players.

Many of the innovative messages that change politics—the idea that gay marriage is pro-family, for instance, or that mass surveillance by the National Security Agency represents liberal big government—aren’t the work of a single strategist. They’re the product of multiple actors sequentially modifying an idea. In the case of abortion, I wrote a whole book about how this happens. The idea of personal freedom, which liberals loved, was gradually transformed by strategists and politicians into a message that resonated with conservative voters: the idea that the government should stay out of the family. That transformation came with policy concessions: parental notice and consent laws for minors, and severe restrictions on public funding of abortions.

Something like that seems to have happened in Arizona. The initial reference to Muslims, in the ADL’s Jan. 16 letter, was relatively benign. The ADL listed several scenarios that could arise under the bill:

An employer could raise SB 1062 as defense to an employee’s equal pay claim … arguing that his or her religious beliefs require that men be paid more than women.

The legislation could be used as defense to paying statutorily accrued interest on liens or other amount owed to individuals or private entities based on a religious objection to paying interest.

A secular corporation with religious owners could refuse to hire someone from a different religion, so as to avoid paying a salary that might be used for a purpose that is offensive to the owners’ religious views.

A Christian-owned hotel chain might refuse to rent rooms to those who would use the space to study the Koran or Talmud.

A Muslim-owned cab company might refuse to drive passengers to a Hindu temple.

That’s a pretty long list. The Muslim scenario came last. The hypothetical target of discrimination was Hindu, not Christian. And that scenario was preceded by one in which a Christian discriminated against Muslims. For these reasons, I think it’s unfair to accuse the ADL of pushing a Muslim stereotype. I wish I had quoted more of the letter to make this clear. I linked to the hearing video in which the letter was read aloud (skip to minute 46), but in retrospect, that wasn’t enough. I’m posting the whole letter here as a PDF, so you can read the full context for yourself.

What happened in Arizona, evidently, is that as other players picked up the Muslim scenario, they removed these mitigating factors. They sharpened it for political effect. The Arizona Republic, in its Feb. 20 editorial against the bill, made the Muslim taxi driver its opening example and changed the driver’s hypothetical victims from Hindus to women. Phoenix news station KTAR did the same in its Feb. 23 report on criticisms of the bill. CBS News changed the victims in the scenario to Jews. Other media outlets changed them to Christians.

Even after the governor vetoed the bill, the scenario continued to spread and morph. Opinion writers condemned the bill as “Sharia Law” and “Muslim Theocracy.” They claimed, as a blanket statement, that in Islam, religious law trumps civil law. Letters to the editor fretted about “a Muslim refusing to do business with a woman who drives.” In some accounts, the taxi driver was replaced by a Muslim barber who “follows Shariah law, so he thinks women have cooties.” These warnings gave conservatives pause. One right-wing website lamented: “Unfortunately, Christian religious rights must suffer in order to stop Muslims from imposing theirs.”

You might find this exploitation of Islamophobia disgusting. You might find it clever. You might conclude that it’s both. Was the political payoff worth the social damage? I’ll leave that question to you. Either way, it’s important to understand that the dissemination and transformation of the taxi driver scenario, like other tropes and characters, is a collective, incremental process. The blame, like the credit, must be shared.