Is reproductive choice—the freedom to have sex without the full natural risk of pregnancy—dangerous? Should it be legally curtailed? Should it be culturally discouraged? Are we competent, as individuals, to manage it?

Ross Douthat raises these questions—some explicitly, some implicitly—in his latest New York Times column. He suggests that banning second-trimester abortions, among other things, might help to restore a culture of marriage. My colleague Jessica Grose rebuts him in Slate. So does Michelle Goldberg in the Nation. But let’s take this debate one step further. Douthat isn’t just challenging abortion. He’s challenging the whole idea of letting women decide whether sex leads to parenthood.

Douthat argues that “the power Roe v. Wade gave women over reproduction sometimes came at the expense of power in relationships.” As evidence, he cites a 1996 Brookings Institution monograph by George Akerlof and Janet Yellen. (Douthat puts Yellen’s name first, but Akerlof is the first author on the paper, so it isn’t clear what Yellen’s role was.) Here’s the part of the paper Douthat quotes, in truncated form, to support his thesis:

What links liberalized contraception and abortion with the declining shotgun marriage rate? Before 1970, the stigma of unwed motherhood was so great that few women were willing to bear children outside of marriage. The only circumstance that would cause women to engage in sexual activity was a promise of marriage in the event of pregnancy. Men were willing to make (and keep) that promise for they knew that in leaving one woman they would be unlikely to find another who would not make the same demand. …

The increased availability of contraception and abortion made shotgun weddings a thing of the past. Women who were willing to get an abortion or who reliably used contraception no longer found it necessary to condition sexual relations on a promise of marriage in the event of pregnancy. But women who wanted children, who did not want an abortion for moral or religious reasons, or who were unreliable in their use of contraception found themselves pressured to participate in premarital sexual relations without being able to exact a promise of marriage in case of pregnancy. These women feared, correctly, that if they refused sexual relations, they would risk losing their partners.

Let’s notice a few significant things about this argument. First, the paper explicitly cites contraception as part of the problem. Second, what made the pre-contraceptive-liberalization era effective, in terms of enforcing a culture of marriage, was the suffering a woman faced if she got pregnant. The basic reasoning here is that what made the good old days salutary was the absence of protection from severe, painful consequences.

Third, these consequences, in the form of stigma, applied only if the woman had the baby. If she aborted it before her pregnancy showed—and if she suffered no complications anyone else knew about—she could avoid the stigma. In other words, the stigma encouraged abortion once the woman discovered she was pregnant. So the argument doesn’t apply equally to contraception and abortion. It applies much more clearly to contraception.

Fourth, the argument puts the weight of enforcement on the woman. She’s the one who has to exact the man’s promise to marry her if he impregnates her. If she fails—that is, if he fails—she’s the one who faces the consequences. And fifth, all she’s getting is a promise. As women throughout history have learned, that promise is often worthless.

The Brookings paper continues:

Advances in reproductive technology eroded the custom of shotgun marriage in another way. Before the sexual revolution, women had less freedom, but men were expected to assume responsibility for their welfare. Today women are more free to choose, but men have afforded themselves the comparable option. “If she is not willing to have an abortion or use contraception,” the man can reason, “why should I sacrifice myself to get married?” By making the birth of the child the physical choice of the mother, the sexual revolution has made marriage and child support a social choice of the father.

Many men have changed their attitudes regarding the responsibility for unplanned pregnancies. As one contributor to the Internet wrote recently to the Dads’ Rights Newsgroup, “Since the decision to have the child is solely up to the mother, I don’t see how both parents have responsibility to that child.” That attitude, of course, makes it far less likely that the man will offer marriage as a solution to a couple’s pregnancy quandary, leaving the mother either to raise the child or to give it up for adoption.

Here, the argument shifts from economic rationality (how men and women behave under the threat of painful consequences) to moral beliefs about the division of responsibilities within a relationship. The first of these two paragraphs focuses on the woman’s responsibility. If she has the freedom to prevent the pregnancy—but fails to do so—the consequences are on her, and the man should be free to walk away. The authors don’t endorse this conclusion, and neither does Douthat. They simply observe that this is how many men reacted to the rise of liberalized contraception and abortion.

The second paragraph focuses on distributional justice within relationships. The argument here is that if the woman gets to decide unilaterally whether to use contraception, have an abortion, or carry a pregnancy to term, then the man, reciprocally, should get to decide whether to help raise the child. Again, this isn’t Douthat’s view. But it’s part of the cultural change he attributes to the rise of reproductive freedom.

When you look at the totality of the argument, what stands out most strikingly is that none of it is about protecting unborn life. All of it is, in Douthat’s words, about “the power Roe v. Wade gave women over reproduction.” It’s not an argument against killing babies. It’s an argument against empowering women to separate sex from parenthood.

Some people despise Douthat for entertaining such ideas. I’m not one of them. We need socially conservative intellectuals to point out socially conservative truths—which, yes, do exist—and that’s what Douthat does. In this case, he has swept himself toward a position I don’t think he has the stomach to defend. The rest of us—those who support reproductive freedom—have a different problem to sort out. If we don’t want to go back to the bad old days, how do we address the decline of marriage? How do we build and preserve stable families in an era of sexual liberty?

Many liberals think money is the sole problem. They believe that if we bolster employment and incomes, our cultural woes will be solved. I disagree. I think Douthat is right that we need cultural corrections, too. One of those corrections, in my view, is an ethic of sexual responsibility. My version would be almost as strict as Douthat’s. But it wouldn’t reject contraception. It would incorporate it.

Here’s the short version. First, for men: If you put your sperm anywhere near a woman’s reproductive tract, you had better be prepared to raise a child with her. Your ejaculation is your signature on a contract authorizing her to carry any resulting pregnancy to term and to enlist you as the father. If you aren’t prepared to sign that contract, ejaculate somewhere else. Don’t complain later that you weren’t consulted about subsequent decisions. The only decision you get is the one at the outset.

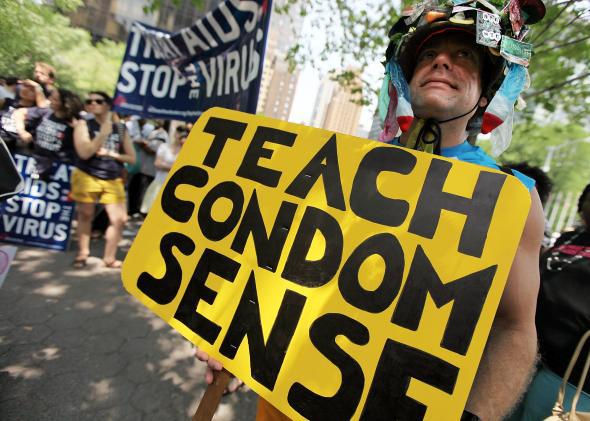

For women: Protect yourself. Unless you’re prepared to be a mother, never have any kind of sex that can lead to pregnancy without using effective birth control. (The same goes for men—even more so, since they have no right to intervene once they’ve deposited sperm.) Do this for yourself, for your partner, and for the child you might conceive. Contraception is awesome. It empowers you to postpone maternity till you’re properly situated. Using that power isn’t just a right. It’s a responsibility.

Some of you might view this advice as too austere or prudish. If so, let’s hear your alternative. If we don’t want to go back to restricting reproductive freedom, we’d better learn how to manage it wisely.