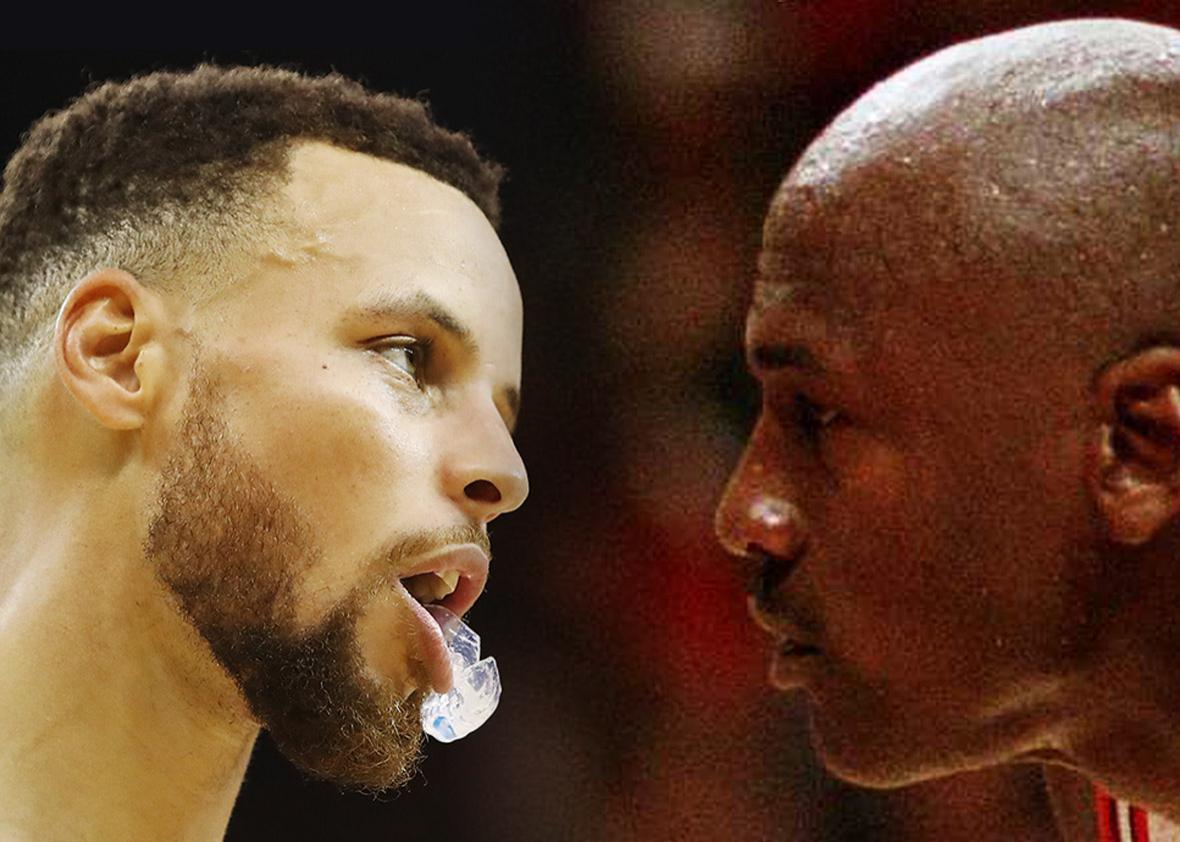

Photo illustration by Slate. Images via Ezra Shaw/Getty Images; Getty Images.

When the Golden State Warriors went 73–9 during last year’s regular season, it prompted an obvious (but fun) debate: Could they beat Michael Jordan’s 1995–96 Chicago Bulls, a team that went 72–10 and has been widely considered the greatest NBA team of all time?

No one was more qualified to chime in on this subject than Steve Kerr, the Warriors head coach who also played on that legendary Bulls squad. In November 2015, after the Warriors had started the season 15–0, Kerr mused about this hypothetical matchup with Ethan Sherwood Strauss. Kerr certainly put some thought into it, and he seemed most excited for the “epic [Dennis] Rodman versus Draymond Green matchup,” one that would feature “a few technicals … maybe a fight or two.”

The transgenerational Warriors-Bulls showdown was a neat thought experiment, but then the 2016 NBA Finals happened. Without getting bogged down in the details—little-known fact: Golden State held a 3–1 lead in that series—the 73–9 Warriors couldn’t stick the landing, and the “greatest ever” debate was put to bed. Then Golden State added Kevin Durant and began the 2017 playoffs 14–0. Rise and shine!

These Warriors may have won six fewer regular season games than last year’s iteration, but Vegas oddsmakers tell us they likely would be consensus favorites against the 1996 Bulls. (The Westgate sportsbook manager set the line for a hypothetical game as Golden State -6.5.) Long story short, a wise-cracking bookie wearing the fashions of centuries past and future appeared before me in the woods and asked if I wanted to place a bet on this nonexistent series. I did, and now I’m sweating the Bulls to pull this off.

The key issue in this fourth dimension–bending matchup is physicality. If it were refereed with the ’90s rulebook, Golden State’s guards would have a miserable time getting open. If the game were played by today’s rules, things would proceed much differently. “They would put their hands all over [Stephen] Curry, and the refs would call a foul,” Kerr said. If the refs were plucked from an entirely separate era, say pre–Reformation France, then they would be too distracted by the electric lights and aromatic and plentiful arena food to call any fouls at all.

For now, let’s focus on the mid-1990s, a time when ice-cold Zimas were flying off the shelves, Weird Al’s relentless lampooning of the Amish topped the charts, and professional basketball players were allowed to “hand-check” with impunity. The NBA’s hand-checking rules are pretty confusing and cover a broad array of on-court sins. Certain hand-checking prohibitions have been around since the 1970s, but the most significant ban was enacted before the 2004–05 season, and it has been enforced strictly ever since. Before then, a perimeter defender could bump his opponent, impede his movement off the ball, pin his forearm against another player to slow him down, or jab at his arms and hands while he drove to the hoop. (Watch this quick video from the Washington Post for a good, concise explanation.) When the NBA made those types of behaviors illegal, the perimeter became a much more peaceful place to be and small ball began to flourish. These Golden State Warriors have essentially mastered basketball in this post–hand-check era. If they teleported to 2017, Jordan and the Bulls would likely have no chance of keeping up.

Another factor to consider is the 3-point line. While the Warriors have better 3-point shooters than that Bulls team, the 3-point line could actually level the playing field between Chicago and Golden State. That’s because the ’95–’96 season was one of three bizarre years in which the NBA played with a shortened 3-point line.

Before the start of the 1994 season, the NBA transformed the three-point arc into a uniform 22-foot parabola. (The standard NBA 3-point line is 22 feet at the corners but extends to 23 feet, 9 inches at the top of the key.) The league was in the midst of a nearly decadelong scoring decline, and this adjustment was one of many the NBA made to crank up the game’s offensive output.

It seems crazy, but that 3-point-line alteration wasn’t seen as that big a deal when it was first announced. In this lengthy New York Times write-up about the 1994 rule changes, the 3-point line gets only a single mention. In 1997, when the line was re-extended to its normal dimensions, the fanfare was similarly subdued.

The shortened line made a huge difference, but teams either didn’t realize it or didn’t care. In 1992–93, before the line alteration, the leaguewide average from long range was 33 percent. By 1995–96, it had jumped to 37 percent, which is better than the NBA’s average accuracy this season (36 percent). Still, teams shot just 16 3s per game in 1995–1996, far fewer than today’s average of 27 per game. It’s as if the league gave offenses rocket-powered Segways, but everyone said, “No thanks, we’ll walk.”

The 1996 Bulls are an excellent case study here. Chicago shot lights out from the shorter 3-point line—40 percent, which would have been good enough to lead the league this year. Each of team’s top three 3-point shooters (Kerr, 52 percent; Jud Buechler, 44 percent; Jordan, 43 percent) shot better than Curry and Klay Thompson did this season (41 percent each).

For the Bulls to keep up with the modern Warriors, they’d need to play with that friendly 3-point line, and they’d need to chuck up a lot more longballs than they did two decades ago. Would the Bulls be willing to conform to the Warriors’ style? In ’95–’96, the Dallas Mavericks led the league in 3-point attempts, shooting around 25 per game. (The Warriors shot 31 a game this season.) In their first game against the Mavericks, the Bulls attempted just 12 3s in an overtime win. They shot six 3s in the second matchup (one of which was taken by Dennis Rodman), and the Bulls won that game, too.

So, who would win? I’ll answer that question with two questions of my own: 1. Do I look like a fortuneteller or some sort of clairvoyant? 2. Are there any major differences between fortunetellers and clairvoyants, distinctions of which I am not aware? I don’t want to make any sweeping generalizations here.

Anyhow, in the future the runaway artificial-intelligence networks that crackle and fizz from pole to pole will get bored and finally provide an accurate simulation of this hypothetical series. Sadly, robots will have rid the earth of humans by then, and no one will get to see the result. Like Ozymandias, all that remains will be the trunkless legs of the Jordan statue that stands outside Chicago’s United Center.