This question originally appeared on Quora, the best answer to any question. Ask a question, get a great answer. Learn from experts and access insider knowledge. You can follow Quora on Twitter, Facebook, and Google Plus.

Answer by Stephen Tempest, qualified amateur historian:

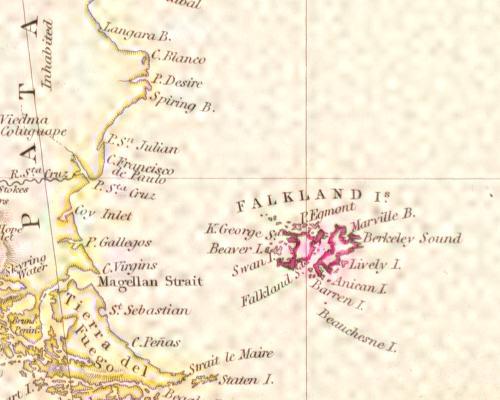

An English ship under Capt. John Strong in 1690 was the first to explore the Falkland Islands in detail, map them, and give them a name. However, that can’t be called an invasion, since nobody lived there at the time except for penguins.

In 1765, a naval expedition commanded by Commodore John Byron (grandfather of the famous poet) surveyed a landing site and established a settlement, called Port Egmont. The first British colonists arrived the following year. The primary purpose was to establish a naval base where ships could be repaired and take on supplies in the region. This might possibly count as an invasion, since a group of about 75 French colonists were living on the islands; they’d arrived the previous year. However, the British hadn’t known the French were there. The two settlements were 85 miles apart and didn’t even find out about each other’s existence for several months. There was no fighting between them.

A few years later, Spain pressured France to hand over its settlement on the Falklands to them. France agreed in return for gold as compensation. Spain demanded that Britain also hand over its settlement on the basis that the entire South Atlantic was a Spanish sphere of influence and nobody else was allowed to colonize it. Britain did not accept this.

Courtesy of Douglas/Flickr Creative Commons

Spain invaded the Falklands in 1770 and conquered the British settlement by force. Britain threatened war; Spain was intimidated and backed down. It returned the settlement on the Falklands to Britain and paid compensation for the damage they’d done. The British settlers returned to their homes peacefully.

In 1774, Britain evacuated its colony on the Falklands since, with rebellion brewing in North America, it couldn’t afford to maintain a naval garrison in such a remote place. It informed Spain that this didn’t mean it was surrendering its claim to the islands and reserved the right to return at a later date. Spain refused to acknowledge this claim. In 1810, Spain also evacuated the islands for similar reasons (war in Europe), leaving them uninhabited.

At some point after 1810, various British seal-hunters, whalers, and others in the region started using the islands as a temporary base—for sheltering from storms, repairing their ships, and taking on fresh water and provisions. Ships of other nationalities—American, French, etc.—used the islands for the same purpose. The sailors were a rough, lawless, and violent bunch, but their arrival wasn’t really an invasion, since there wasn’t anybody to invade.

In 1828, Louis Vernet, an Argentinian citizen, set up a cattle-ranching business on the islands to sell meat to the sailors. He employed a few dozen staff (of many different nationalities) plus their families. In 1829, the government in Buenos Aires appointed Vernet official governor of the islands in its name. Britain sent a diplomatic protest stating the islands were its territory and Argentina had no right to do this; Argentina ignored it.

Vernet started confiscating American ships and their cargoes in the region on the grounds that they were violating Argentine sovereignty by hunting without his permission. The United States government refused to recognize Argentine rights to the Falklands and accused Vernet of piracy. Eventually in 1831, a U.S. warship was sent and U.S. Marines occupied the Falklands. This was an invasion—though a bloodless one—but it was American, not British. About half of Vernet’s employees were either arrested for piracy or chose voluntarily to leave the Falklands. Two dozen of them remained on the islands.

In 1832, Argentina sent a new detachment of troops to reassert its claim to the Falklands. These troops promptly mutinied, murdered their commander, raped his wife, killed several of the other settlers, and escaped into the hills to live as bandits. After several months an alliance of the few remaining loyal Argentine troops, and various British and French sailors from the ships in the Falklands’ harbors, recaptured the mutineers.

The British government was disturbed by the reports of piracy and banditry in the region, which were a threat to trade and commerce. It still regarded the Falklands as British territory and were mildly alarmed at Argentine claims in the region. It was very alarmed at U.S. warships landing troops there. It decided to reassert sovereignty. In January 1833, a British warship arrived in the islands and ordered the Argentine flag to be hauled down and be replaced by a British one. (As the British phrased it, the Argentine flag was being flown illegally on British territory, so it very politely asked that it be taken down. The flag was then folded and given back to the Argentine commander.)

This is presumably what’s most often referred to as an “invasion,” but there was no fighting. The most senior Argentine commander left alive after the mutiny had almost no loyal troops left and had been relying on British mercenaries for support—and those British were not about to shoot at their own countrymen. Under protest, he sailed back to Argentina, taking with him the captured mutineers in chains. (They would be executed after returning to Buenos Aires.)

That left only a couple of dozen settlers left on the island, most of them Vernet’s employees, although they hadn’t been paid for two years. Contrary to the story often recounted in Argentina today, they weren’t expelled by the British. For example Antonina Roxa, a woman who arrived in the Falklands as one of Vernet’s employees in 1830 to work as a cattle herder, ended her life aged 62 as a naturalized British citizen owning 6,000 acres of land on the Falklands. The islands gradually became a more peaceful place; sheep farming was introduced in the 1850s, and by 1900, about 2,000 people were living there—some descendants of Vernet’s original settlement, some arrived from nearby Latin America, but most of them settlers from Scotland.

In 1850, Argentina quietly dropped its claim to sovereignty over the Falklands, at least on an official basis, in return for British concessions in other areas. However in 1941, as Nazi Germany seemed near to victory, the pro-fascist government of Argentina formally revived its claim to the islands. After World War II, this claim continued to be made, but now worded in the language of decolonization and anti-imperialism. (Rather ironic considering that the Falkland Islanders actually are the indigenous inhabitants of the islands, but Spanish-speaking Argentinians are not the indigenous inhabitants of Argentina.)

In 1982, Argentina invaded the islands by force and conquered them. Britain launched a successful counterattack and took them back. That could be classed as an invasion, but the term liberation would also apply.

More questions on Quora: