This question originally appeared on Quora, the best answer to any question. Ask a question, get a great answer. Learn from experts and access insider knowledge. You can follow Quora on Twitter, Facebook, and Google Plus.

Answer by David Bliss, former graduate student at the University of New Mexico:

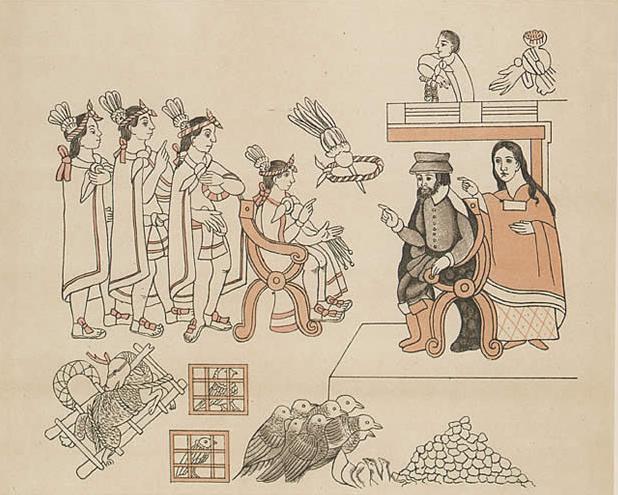

First, Hernán Cortés in particular did not conquer the Mexica Empire (commonly known as the Aztecs, though this isn’t really correct) with just his Spanish soldiers. He had a tremendous number of indigenous allies who didn’t like being subjugated by Tenochtitlan and likely thought they could deal with the Spaniards afterward.

In both Mexico and the Andes, disease played a huge role in facilitating the conquests and subsequent colonization. In Mexico, diseases ravaged Tenochtitlan before Cortés captured the city, and in the Andes European diseases had actually arrived prior to Francisco Pizarro and killed the previous Inca ruler, Huayna Capac, leading to a succession crisis and civil war that seriously reduced the empire’s ability to resist. Waves of epidemics also hurt subsequent efforts at resistance against the Spanish regimes in their early stages.

Second, common assumptions about Spanish conquest and colonization are wrong as a result of how we tend to assume colonialism operates in general. The conquests of Mexico and the Andes were not state-sponsored enterprises. In landing in Mexico and seizing Tenochtitlan, Cortés defied the order of the governor of Cuba and at one point had to turn back to the coast to fight other Spaniards and prevent his own arrest for doing so. Likewise, the Spanish crown reacted with quite a bit of horror when it learned that Pizarro had executed Atahualpa, emperor of the Inca.

Nor was the colonial system put in place by the Spanish centralized in any real way. Both in Mexico and the Andes, conquering Spaniards were able to absorb huge areas and populations because they largely kept in place the power structures that had existed prior to their arrival, even if they renamed them. Traditional local authorities were kept on as local officials, and for many people life under the Spanish was hardly any harder than it had been under the Mexica or Inca, who were also both very oppressive. That said, the effects of subsequent waves of epidemics were obviously horrible, and after years of depopulation the Spanish did break from traditional local imperial practices, often dislocating entire populations and settling them forcibly where they hadn’t lived before and had no ties to the area or their new neighbors. This was exacerbated with the discovery of lucrative mines, which the Mexica and Inca hadn’t always exploited.

In general, it’s important to understand just how decentralized Spanish colonialism was. This followed similarly decentralized rule of Spain itself by Castile, and it meant that colonial officials fought with each other constantly and prevented the establishment of an entrenched New World aristocracy, which was the crown’s greatest fear really.

Third and finally, people in the English-speaking world are influenced by the so-called Black Legend. Protestant polemic writers in the 16th and 17th centuries, hoping to convince people that the Spanish Catholics (and by extension, other Catholics) were brutal and violent, spread a lot of half-truths and exaggerations about the brutality of Spanish exploitation in the New World.

Of course, the conquests and colonization were undeniably brutal, but not on the scale or in the way that English writers characterized them. The most brutal and violent periods were the early colonization of the Caribbean, which led to the total depopulation of most islands, the violence of the conquests of Mexico and the Andes themselves, and the work regime in mines. English writers exaggerated the scale of these atrocities and spread stories about Spaniards opening markets selling human flesh as food, for example, for which there is no historical basis.

Again, none of this is to excuse or minimize the horrors of colonization. But while the English were spreading these stories about the Spanish, they were committing pretty much identical atrocities in North America. In fact, the Spanish actually went to greater lengths in many real ways to treat the indigenous people in their colonies better than the English did: Because the Spanish firmly and sincerely saw it as their responsibility to convert the indigenous people to Catholicism, it was official policy that indigenous people were not to be enslaved, and they had most of the same rights and privileges as other Spanish subjects. Colonial legal records are full of cases where indigenous people use the courts to their advantage and protect themselves within the colonial justice system. We tend to assume that any system like that could only ever exist to systematize oppression, and while indigenous people of course had a harder time than white Spaniards at using this system to their advantage, there were no formal laws keeping them from doing so, and they intelligently navigated their way through the courts regularly.

The decentralization of the Spanish colonies also meant that there was plenty of room for people to advocate on behalf of indigenous rights and curtail abuses. Bartolomé de Las Casas was the most famous of these people, but he was far from the only one, nor was he the first. Las Casas and others went so far as to call for land to be returned to indigenous people wholesale. And these were not fringe voices—Las Casas appeared in court in Spain arguing that the indigenous people of the Americas should enjoy full rights as Spanish citizens, and he won. The brutal encomienda system of labor exploitation was put to a stop thanks in large part to Las Casas and his supporters, who correctly argued that the system effectively enslaved indigenous people, despite the Crown’s ban on it.

So misunderstandings about Spanish colonialism are due generally to false assumptions about how colonialism in general operates, as though 19th-century colonialism in India is necessarily the same as 16th-century colonialism in the Americas, and due to lies and lack of perspective on the part of English writers who conveniently overlooked English colonialism’s own, arguably more brutal, violence.

More questions on Quora: