This question originally appeared on Quora.

Answer by Cristina Hartmann, author:

As someone who’s losing her sight to retinitis pigmentosa (RP), I face this question every day. I, however, have Usher syndrome, which couples deafness and gradual vision loss, so I’m not representative of the average blind and low-vision individual.

That being said, as someone who has moved from sighted into legal blindness, I’ve noticed certain interesting changes in my lifestyle and how people treat me. This isn’t a subject that can be explained briefly, so please forgive me in advance for my lengthiness.

People seem to think blindness as binary: You’re either completely sighted or completely blind. The truth is that there are infinite ways to be legally blind.1

Not just is there a large range of sightedness between fully sighted and completely blind, but there are a lot of variations within that range. Some blind people have acuity issues; others have blind spots but otherwise clear vision. Many are somewhere in between. Few are completely blind.

So, what I see is unique to me and my condition. No other blind person will see as I do.

My condition causes night blindness, gradual peripheral vision loss, and in its advanced stages macular issues. Even though it’s a progressive condition, it progresses differently for everyone.

My lower and upper fields of vision have been gone since my early to midteens. I have blind spots in the sides of my vision, but I can detect light and movement in my far peripheries. The funny thing is that I don’t actually see the blind spots. My brain has reconfigured my visual perception to skip over the blind spots, so things actually seem as if I have 180-degree vision. Based on my last field test, I have somewhere between 25 and 35 degrees of vision, so my brain is constantly tricking me.

Two years ago, my RP began affecting my macula (the central part of the eye), which is a somewhat unusual development this early. The macula affects color discrimination and visual acuity. As of right now, I have about 20/150 in the left eye and 20/300 in the right, both uncorrectable by glasses.

Everything seems out of focus. If a person is standing more than 2 feet away from me, his or her face is as blurry as in a Monet painting. Typically, I identify a familiar person by his silhouette and the way he walks (since I can’t recognize voices with much precision). Even up close, I can’t see fine detail like smaller scars and roughness, so people all look like they have amazing skin.

Bright light makes my vision worse. It seem like a thin white film is covering everything, making light-colored things almost glow. Oftentimes, harsh direct light will create shadows that confuse me, since the world becomes too visually complicated. Certain shadows might look like steps to me since my distance perception is basically zero.

The situation is similar for dim places. Everything goes gray (or black if it’s quite dark). I can’t see depth or shadows in the night; it’s just one big wall of black dotted by streetlights.

I see quite well under the perfect conditions: evenly distributed light of medium intensity with simple and high-contrast items plus relatively stationary people and things. But … life rarely provides perfect conditions.

Navigating the World With Blurry Restricted Vision

There are three main navigation techniques that blind and low-vision folks use: a white cane, seeing-eye animal, or nothing. There are some political and personal preferences involved in one’s choice.

Many people who don’t have vision loss push me to get a dog. They seem to feel more comfortable with the idea of a seeing-eye dog. Some of them even think that it’s a cool way to get a very well-trained pet. It’s not that simple.

A white cane can be put away at any time. A white cane doesn’t shed, poop, require vet visits, or develop a mind of its own. Nobody wants to pet a cane, either. Seeing-eye dogs are wonderful but have a lot of overhead. It’s a personal choice dependent on one’s lifestyle and needs.

As simple as the white cane may be, it still requires training.2 There are different holds, arcs, and contacts. You hold and move it different ways, depending on how many people are around you and your familiarity of the area, among other factors. The white cane gives you a lot of information, but there are a few things that get me: chairs and tables (my cane simply slips underneath), overhanging brush (again, my cane isn’t high enough), and cracks (sometimes my cane will bounce back, which is annoying).

You learn how to map out the world differently. Instead of reading the street signs, you count the number of intersections. You stop using the pedestrian signals to know when to cross the street, but look (or listen for) the traffic flow. (Many blind and low vision folks also use GPS systems, but it’s usually too noisy for me to hear the instructions, so I don’t use GPS very often.) Landmarks, such as a distinctive building or a fire hydrant orient you to the world around you. Memory becomes crucial.

Sometimes I use a human guide. I hate to do this, not just because it limits my independence, but because most people … are terrible at it. They’ll grab you and proceed to drag you, making you stumble and become disoriented. They’ll forget to stop before a step, so you fall. Even with instruction, guiding someone else is an intuitive exercise that not a lot of people have a talent for.

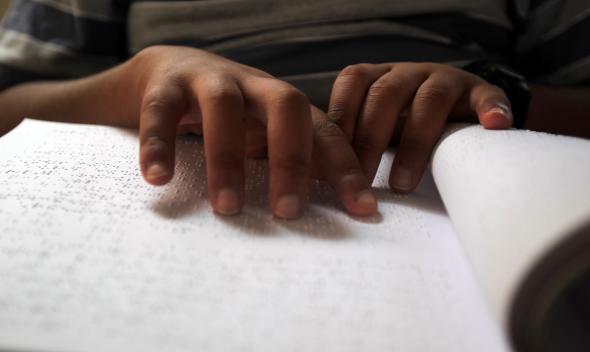

How the Blind Read

Since I’m deaf-blind, this is a different endeavor for me than it is for the average blind or low-vision individual.

I remember when I was sitting with a low-vision specialist. She kept telling me that I should use the text-to-speech software on my computer. “But I’m deaf, so … wouldn’t Braille be better?” I asked her. “You can hear me, so you can hear the computer.” (I have a cochlear implant, so I can hold a conversation reasonably well, but it’s not perfect.) I explained to her that it wouldn’t be easy for me, and I’d probably end up missing words and get tired, but she still insisted that it was the best course.

I ignored her and learned Braille. Right now I’m about 60 to 70 percent of my old reading speed, and I’m pretty goshdarned proud of myself.

My point is that people can be dogmatic when it comes to alternative reading techniques. Some people will advocate that a person with low vision read visually, regardless of how slow or difficult it is. Others will advocate auditory-only training, since it provides most blind and low-vision folks the fastest transitions. So there are some politics involved. Each blind and low-vision individual should choose whichever reading technique fits his or her needs the best: visual, auditory, or Braille.

For more information about assistive technologies:

- How long does it take to learn Braille, and does it get harder as you get older?

- What is it like to use a refreshable Braille device with a laptop or tablet?

How People Treat You

The biggest change after I started to use my white cane was the loss of my anonymity. With a cane or a seeing-eye animal, people notice you because you’re different. This is good and bad.

I usually get excellent customer service at restaurants, stores, and offices with employees going out of their way to make sure my needs are met. I’m very grateful for these employees. Most people are willing to give me directions. I get on first on flights and sometimes get placed in the first row. Crowds part like the Red Sea when I approach. Kindness has been the general rule.

As with any rule, there are exceptions. Some people stare or back away from me as if I’m infectious. (They think I don’t see them, but I do.) There are also people who overcompensate in their kindness. Once, I asked this woman for directions, and she proceeded to lead me, step by step, to the front desk of where I was going. When she tried to take over, I had to tell her firmly that I was fine and that she should go on with what she was doing. Her intentions were good, but overweening kindness is almost as insulting as people who flinch.

Since I’m no longer anonymous, people watch me. I feel constant pressure not to stumble or fall, which is tough since I’m a generally clumsy person and relatively new to using a cane. It’s a dispiriting feeling—the sense that you can’t make a mistake, that you can’t trip.

I often find myself missing my anonymity the most. (But it is nice to get in front of the line in amusement parks!)

The Emotional Side of Losing One’s Vision

It’s the change that’s the hard part, not the vision loss itself. People born blind don’t need to struggle with this aspect; people like me who lose their sight later in life do.

The most destructive part of losing one’s sight is the feeling of incompetence. As someone who’s not naturally organized and orderly, the new way of interacting with the world can get rough. I’ve broken or cracked more than half of my set of drinking glasses by dropping or knocking them over. I vacuum up electrical cords because I forgot to check for stray cords. I’ve walked into people by accident. I’ve stepped on my cats too many times to mention, and I’m afraid that one of them holds a grudge.

I’m the kind of person who hates feeling inept. I like doing things well; to a certain degree, I’ve done many things well. At times, I feel like a failure at adapting. When I misplace something for the umpteenth time, I find myself berating myself for not being better at being blind.

I’m getting better, though. I haven’t cracked a glass in months. The electrical cords haven’t been ruined by the vacuum in almost a year. My cats now know to avoid me when I’m moving quickly. Adapting is a much slower process than I ever expected, but it’s moving in the right direction.

One of the more discerning aspects of vision loss was how my conception of myself has changed. Even though I’ve known that I had RP since childhood, I’ve never thought of myself as blind. I’m starting to think of myself that way now. I’ve stopped squinting, thinking that I would see better, only if I tried harder. My self-consciousness about the white cane is waning. I’ve even started dreaming of myself as I am: an awkward, clumsy blind person.

The path to acceptance is a slow one, full of cracked glasses and disgruntled cats, but I’m getting there.

__________

1Legal blindness qualifies one for certain services from the U.S. state and federal governments, including the right to use a white cane or a seeing-eye animal. Moreover, legal blindness applies to people who are blind and have low vision. (Return.)

2 Trained professionals called Orientation and Mobility (O&M) Instructors are typically ones who provides this training. Depending on the state that one lives in, this service is provided by non-profit organizations or contractors, among others. Competence really varies. I’ve had good and bad O&M instructors and the difference is amazing. (Return.)

* * *

Answer by Janice Strange, blind for 13 years and workw with the blind:

This question really depends on if you are born blind or go blind later.

If you are born blind, it does not feel like anything. People do not see black. They see nothing. To them it is completely normal, as they do not know any other way of life. It is like asking what does it feel like to be white, black, or any other race. It just is who you are. People describing things in terms of color gives you an idea, but it is still based on your thoughts and not what color really is. For example, you know an apple is red. So when they say she is wearing a red shirt, you think apple. However, whether that image is the same red as everyone else sees is irrelevant and inconsequential.

Going blind is different, though. It depends on when you go blind. The younger you are when you go blind, the easier and more normal it feels.

If you go blind as an adult, like I did, it is very weird in the beginning. You do see black, and you know you are missing things. At first, when you dream, you can see, but over time, you start dreaming as you are blind. This is because your brain starts accepting the blindness, and it is your reality. Given enough time, it becomes normal, and you stop thinking about it.

However, there are things you miss because you once knew them, like looking at your new baby. People can describe things to you, and it helps because you do have a solid reference to it.

More questions on Blindness: