This question originally appeared on Quora.

Answer by Andrew Warinner, code monkey, expat, utility infielder:

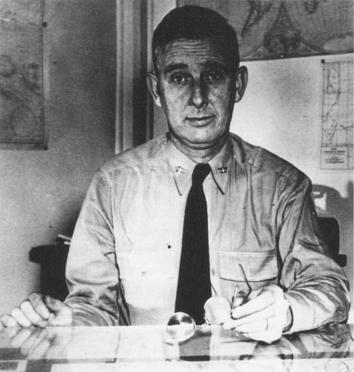

Courtesy of U.S. Naval Historical Center/Wikimedia/Creative Commons

The U.S. had an excellent track record against Japanese codes and ciphers before World War II, and this experience, combined with a variety of other sources of intelligence, helped the U.S.—primarily the radio interception station and decryption center Station HYPO run by Capt. Joseph Rochefort at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii—deduce that an attack on Midway was in the offing.

Japanese naval codes were unlike German codes in World War II. They were primarily “book” ciphers, while German codes used mechanical encipherment—the famous Enigma and Lorenz machines.

Book ciphers work like this: The sender composes his message and then consults the code book. Common words and phrases are replaced with a group of numbers and letters, and any remaining text is encoded character by character. The result is transmitted. The receiver then looks up each group in the corresponding code book and reassembles the message. An additional level of security can be added by enciphering the code groups themselves; this is called superenciphering.

High-grade Japanese naval codes since the 1920s had relied on code books and superencipherment to protect their communications, and the U.S., Great Britain, Australia, and Holland all had had considerable success against them. The Imperial Japanese navy did regularly change their code books and the superencipherment technique, but the supherencipherment was generally weak and easily broken (Japanese characters were encoded as romaji for transmission, and this made them vulnerable to standard cryptological attacks such as frequency analysis). The code books themselves were also not radically changed (words and messages were organized alphabetically, and sections of code groups were incremented consecutively).

The main Japanese naval code, the Navy General Operational Code, dubbed JN25 by the U.S., had a code book of 90,000 words and phrases. Even when the superencipherment was stripped to reveal the code groups (nine character combinations in the case of JN25), the meaning of each code group had to be inferred.

Deducing the contents of the JN25 code book was essentially an exercise in puzzle-solving. The meaning of particular code group could be inference by context or by cross-referencing its use in other messages. Codebreakers at Station HYPO were known for their prodigious memories, but they also made extensive use of IBM punch-card sorting machines to find messages using specific code groups. The end result was a huge card catalog representing the inferences and deductions of code groups of the JN25 code book.

So in early 1942 when the U.S. began detecting signs of an impending attack, the target was encoded as “AF.” Locations in the JN25 code book were represented by a code group, and AF was not definitively known by the U.S. Other intelligence methods such as traffic analysis pointed to a target in the Central Pacific, but other U.S. naval intelligence organizations, particularly OP-20-G in Washington, D.C., disagreed about the location and timing of the impending attack.

So the codebreakers at Station HYPO devised an ingenious experiment to confirm the identity of AF. Pearl Harbor and Midway Island were connected by an underwater cable that was invulnerable to Japanese interception. Station HYPO sent orders to Midway by cable to broadcast a radio message that the island’s desalinization plant had broken down. The radio message was broadcast without encryption to ensure that Japan could read it if it was intercepted.

The radio message was duly intercepted by Japan and reported by a message encoded in JN25 stating that AF’s desalinization plant was out of order. That message was intercepted by Station HYPO. AF was thus confirmed as Midway.

There remained the question of the timing of the attack. Station HYPO concluded that the attack would come in late May to early June 1942, while OP-20-G said late June. Station HYPO won out again because they had succeeded in cracking JN25’s date encryption and OP-20-G had not.

Station HYPO’s intelligence persuaded Chester Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, to risk the three remaining U.S. carriers in the Pacific in an attempt to ambush the Japanese attack on Midway. While Midway was a stunning victory for the U.S.—sinking four Japanese carriers for the loss of one U.S. carrier—that was enabled by intelligence and broke the uninterrupted string of defeats and draws the Imperial Japanese navy had inflicted on the U.S. Navy, much hard fighting remained and more stinging defeats awaited the U.S. in the Pacific.

The bureaucratic feuding between Station HYPO and OP-20-G continued for the remainder of the war. Rochefort became a victim of the infighting; he was never promoted beyond captain, never received the sea command he wanted, and received no decoration or award for his invaluable work at Station HYPO during his lifetime.

More questions on Military History and Wars: