This question originally appeared on Quora.

Answer by Cristina Hartmann:

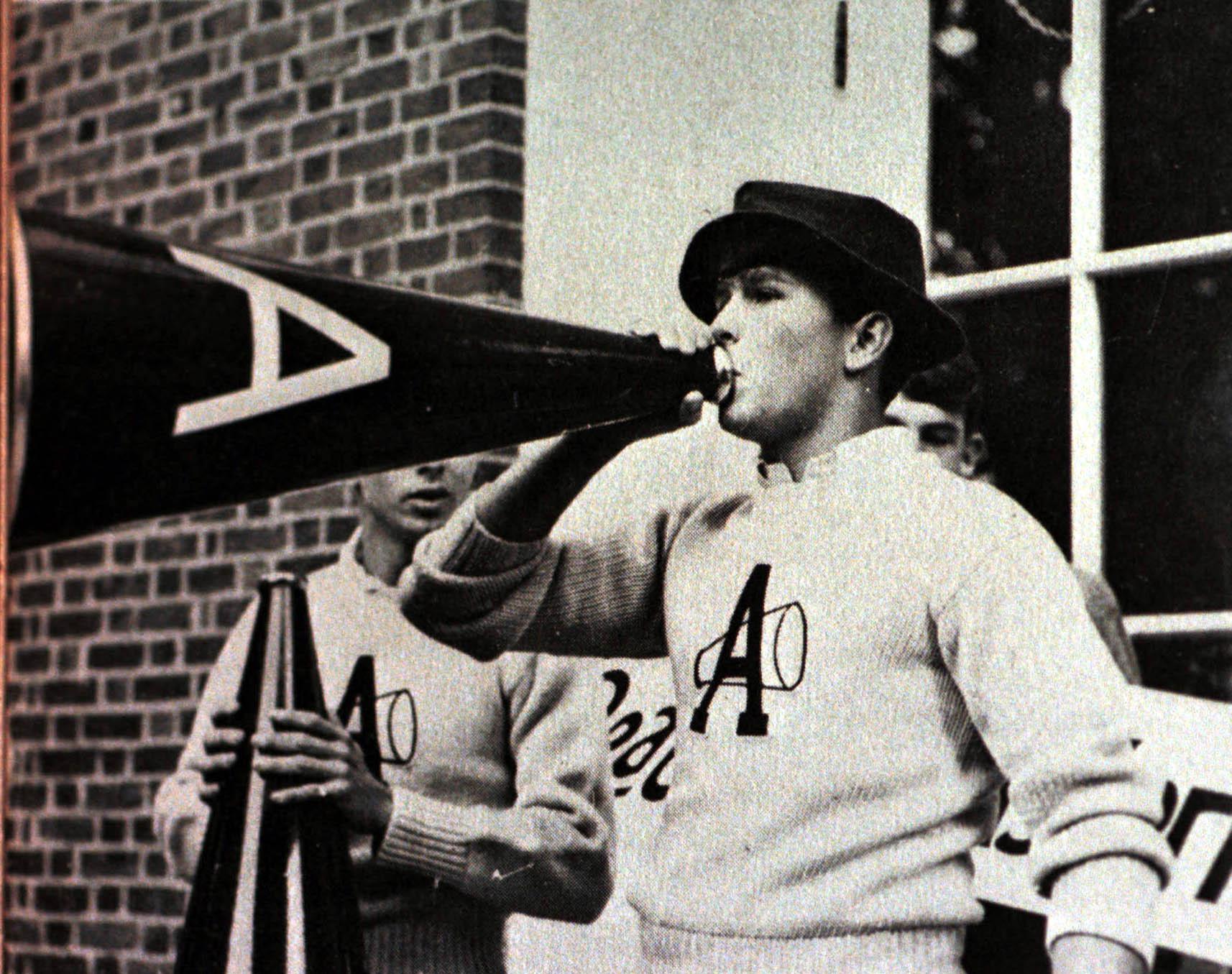

I attended Phillips Academy from 2001 to 2003 for my last two years of high school. It was at Andover where I learned that luck isn’t evenly distributed.

I’m not what you’d imagine a typical boarding school student to be. I didn’t even know that schools like Andover, Milton, and Exeter existed until the year before. My parents are teachers, and I ended up using scholarship money to go. I come from immigrant stock, nary a drop of blue blood to be seen. A number of my childhood friends barely finished college (if at all) and hover above the poverty line.

Not only was I a hick from semi-rural upstate New York, but I was a lazy one. I was a good student, but I wasn’t at the top of my class. My winning studying technique was to watch TV with a book open on my lap, deigning to study during commerical breaks. At my previous high school, transcripts only showed the average of the quarters’ grades and finals. My strategy was to slack off for the first two or three quarters, getting B’s and the ocassional C, then working hard to get A-pluses on the final and the final quarter. The result was a pretty decent honors transcript with mostly A’s and A-minuses.

I’m still surprised Andover even let me stand on the Knoll, let alone allowed me to attend.

Moreover, as far as I know, I am the first (and only) deaf student to attend Phillips Academy. Legally, Andover wasn’t required to provide me with any services, being a private institution. Andover, however, provided the best services that I’ve ever gotten anywhere. I got two sign langauge interperters. Two. At most schools, I had to fight for a single mediocre interpreter. At Andover, they handed over two excellent interpreters without a blink. Money wasn’t an issue.

After an inauspicious first day (September 11th, 2001), I encountered an entirely new world at Phillips Academy. It wasn’t a bad world, but it was certainly different than my old world of ordinary folks.

During my first month there, I was walking along a hallway in the gym, peering into the window that oversaw the pool. I saw some girls in the pool flinging a ball to each other, wearing funny swim caps that went over their ears and had straps under their chins. I pointed at the girls and asked, “What is this?” One of my dormmates responded, “That’s water polo.” I answered, “Wait, there aren’t any horses in water polo?” Yes, I thought that water polo was an aquatic version of polo that Prince Charles plays. Over the next two years, I also learned about crew, $100 umbrellas, and the skiing in the Swiss Alps (not from personal experience).

Don’t get me wrong, not everyone at Andover came from money. One of my friends was on a full scholarship (Andover admissions is need-blind) and had to go to a state school because she couldn’t afford to go to a private university without a full ride. Andover is a lot more diverse (racially, socioeconomically, and geographically speaking) than you’d expect, but there are certainly people from old money as well as no money. At Andover, it was oftentimes hard to tell the difference between the two.

Cultural shocks aside, Andover expected far more of me than any of my previous schools had. For the first time in my life, I had to study and study hard. It’s not just that the material is harder (it is), but that you’re measured by a bigger and fancier yardstick. Your peers are smart and driven, high performers since the age of 5. You swim with them or you don’t. (I, however, recommend that you don’t try to swim with the student who went to the Olympics at 13.) For someone like me, it was a wonderful and much-needed kick in the seat of the pants.

Not only did Andover have dedicated buildings for subject areas (plus its own indoor track and pool), but it also had a course offering rivaling a small college’s. If you were a math genius (I wasn’t), you could take college-level linear algebra classes. If you were an English whiz, you could take a class dedicated entirely to Jane Austen novels. The classes and teachers were incredibly flexible in how they taught. Andover was the first place that rewarded me for my “creative” way of expressing myself in writing. You had to attend Saturday classes once a month as payment, or as revenge, depending on how you looked at it.

Despite the fact that blue-blood money matters less and less in today’s world, there’s something empowering about knowing that great men and women once sat where you’re sitting. It fills you with confidence that the world is yours for the taking. That confidence brings you luck and opportunities.

Plus, I knew at least a few of my classmates would make it to high places. It’s a surreal feeling to know that you could be rubbing elbows with future CEOs and United States presidents. It’s not just future potential; you also get to meet some pretty high-up folks at Andover. In my two short years there, I met George H.W. Bush, Desmond Tutu, and Peter Jennings, among others. Being surrounded by great men and women makes you want to be great too.

For many, Andover was just the start of a string of prestigious insitutions. When the college admissons season rolled by, everyone knew where people got in (and didn’t). You see, the mailroom is a social centerpoint, one of the few places where students could just hang out. Everyone could see a fat (or skinny) envelope you took out of your mailbox. I even got a few comments about why I went to Cornell over my other options (some of which were more highly ranked and respected).

At our graduation, we didn’t wear a cap and gown. Instead, the girls wore white dresses and boys wore blue blazers with khakis with bagpipes blasting as we walked. How delightfully preppy is that? It was pretty damn picturesque, which is more than I can say of most high school graduations.

After Andover, I’ve gotten mixed reactions, ranging from “Uh? What’s a boarding school?” to “Poor you, your parents must’ve hated you” to “Wow, fancy-pants!”

It’s the Harvard Syndrome to a lesser extent. People who know what Andover is will reassess you upon finding out your pedigree. You either rise or fall in their estimation. Some will assume that you’re a terrible snob; others will assume that you’re a rich genius. People, including yourself, also expect more of you. People who attend top boarding schools aren’t supposed to fail. They’re supposed to become presidents or something.

Ten years after graduating, I look back on my time at Andover with great fondness. It was at Andover where I discovered that I could run with the big boys. I grew more confident about my own abilities, enabling me to take calculated risks and to follow my own dreams. For that, I owe the admissions committee at Andover an eternal thanks.

…

Answer by Eva Glasrud:

I attended Phillips Exeter Academy from 2001-2005.

I did not know when I applied—nor, indeed, until I was on the bus from the Boston Airport to PEA—about the 8 a.m.-6 p.m. class schedule. I don’t think I even really understood about Saturday classes, either. So that was a bit of a surprise.

But once classes started, I didn’t really mind either of those things. Classes were awesome. We weren’t lectured at. We weren’t expected to spend hours memorizing facts and completing busywork. Classes were about thinking and communicating—and what could be more important than that? Everything was discussion-based, and we were expected to learn as much from our classmates as from our teacher.

And I think this is one of the major ways in which elite schools differ from honors programs in public schools. A lot of “honors programs” are the same as the normal program … you just read the books twice as fast. This is not an engaging way to learn. This doesn’t teach you how to think—just speed read and memorize.

Part of the problem is that most teachers aren’t trained to work with gifted youth. And most public schools don’t have the resources to provide the richest possible experience to them.

But top boarding schools tend to have experienced teachers, large endowments, and generous alumni. The year I started at Exeter, a brand new, $40 million science building opened. In it, we had an aquarium, touch pools, a humpback whale skeleton, and all kinds of lasers and electronics and chemicals and gadgets to make learning awesome.

Our campus also featured the world’s largest secondary school library, with over 100,000 volumes. If, somehow, the book/movie/journal you needed wasn’t there, you’d just tell the librarians, and they’d order it for you. We had a nutritionist, free and confidential mental health services, a wonderful music program, and about a billion languages to choose from. These are opportunities that are hard to come by elsewhere.

In spite of all that, one of the best and most beloved resources is the classmates. Think of it this way. There are a ton of really bright 13-year-olds in the world. And a lot of them end up going to college and doing great things.

But how many of those kids are so driven and so excited about learning that they can’t wait until they’re 18 to begin their journey? That they take the SSATs, get 4-5 teacher recommendations, fill out a very comprehensive application, submit their transcripts, and attend either an on-campus or alumni interview? Because they want a bigger challenge? When they’re 13?

They are some of the most intriguing and least complacent people I’ve ever met—and that’s awesome. It’s wonderful to be around peers who want everything. Especially in a world where so many people are passive recipients of life.

Your classmates inspire you, and you form really special bonds with them. You all start out in the same boat—you’re there, at this school, 14 years old and (semi) on your own. You live together, study together, play sports together, and eat every meal together. You get up at 7:30 a.m. on Saturday to eat breakfast and go to Latin class together. You get really close, really fast.

It’s a special kind of relationship I haven’t really witnessed anywhere else. And yet, some of your favorite friendships are with your teachers—many of whom are qualified to teach at a college or university, but who chose, instead, to work closely with a special group of kids at a truly magical place.

In the old days, they used to say, “Exeter is not a warm nest.” But things have changed—Exeter is a very warm nest. If you ever need help on an assignment, your dorm is full of older students who have taken the class and can point you in the right direction. If you do badly on a test, the teacher will invite you to breakfast in her home to bring you up to speed and talk about what you can do differently next time.

As recently as 20 years ago, many boarding schools didn’t have as much Internet as they do now. They had one phone per dorm, and students would call home once a week. But today, there is Internet in every building. There is one phone line per person per dorm room (in addition to the cell phones almost every student carries). It’s very cheap and easy to stay in touch with your family—and even if it weren’t, you’d probably be too busy to miss them, anyway.

Finally, there is a common misconception that people who go to boarding school are rich snobs. This is not so. Apparently money used to be big, and need-based scholarships used to be stigmatizing. But today, most of the top schools are either need blind, or offer generous financial aid packages to their middle- and low-income students. When I went to Exeter, something like 35 percent of us were on some form of financial aid. Today, that number is closer to 50 percent.

In fact, Phillips Exeter Academy is free to those with need. As of 2007, any student whose family makes $75,000 or less attends the academy for FREE. (Normal tuition, room, board and mandatory fees total about $46,900/year.) Moreover, the admissions office spends a lot of time and money recruiting students from rural and inner city areas. This all makes Exeter a more diverse experience.

I can’t speak highly enough of my experience at Exeter. If you have any further questions, feel free to ask.

Note: Although they had Saturday classes when I was a student, Saturday classes are no mas. I was sad to hear it: I think they really added to the Exeter experience.

More questions on boarding schools: