Fifty years ago this month, the Supreme Court of New Jersey recognized for the first time the right of “well behaved apparent homosexuals” to congregate in bars. This landmark but little-known decision, One Eleven Wines & Liquors, Inc., v. Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control, is worth revisiting on its semi-centennial for several reasons.

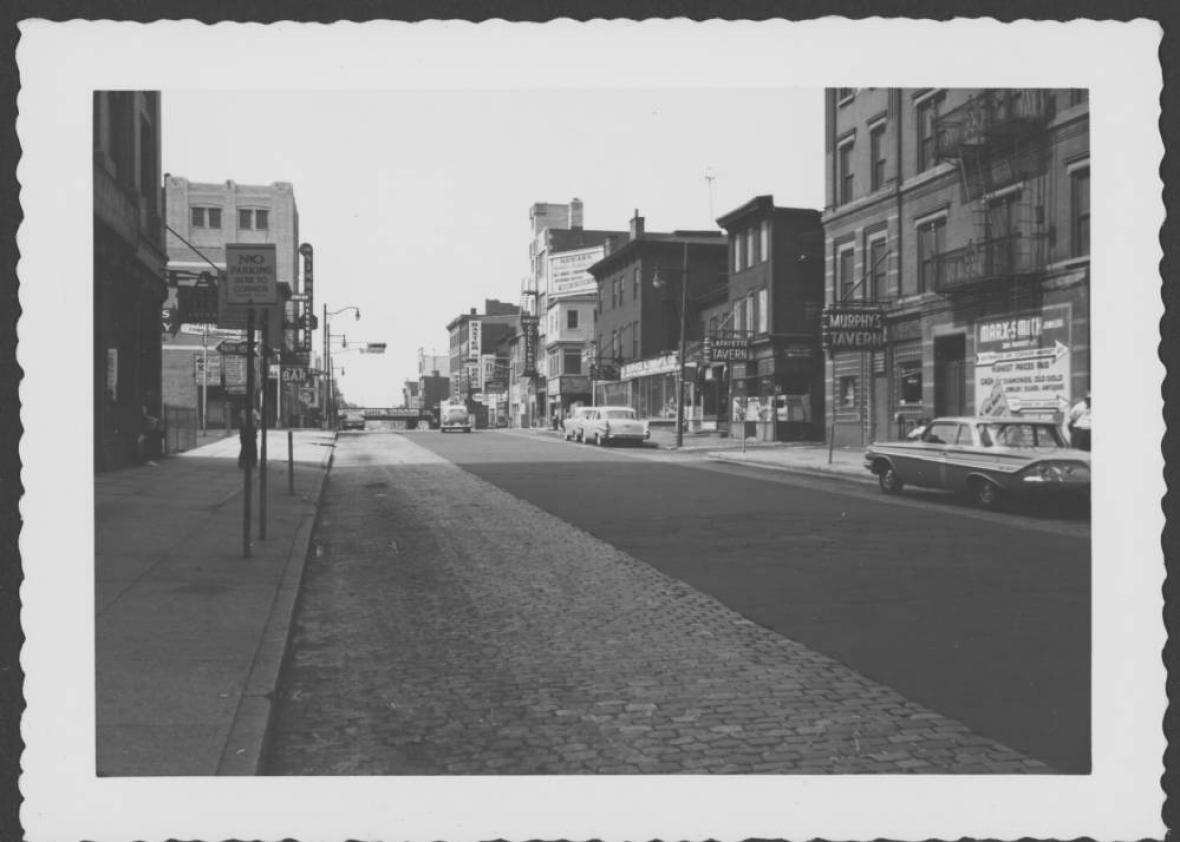

First, it reminds us that the iconic 1969 Stonewall rebellion was preceded by many smaller, incremental victories for LGBTQ people. Second, the key role of Murphy’s Tavern in downtown Newark helps recast our memory of urban history. Newark in the year 1967 is mostly recalled for the explosive violence between African American residents and white National Guardsmen that July, but the city also has a rich, multiracial queer history. (The state’s high court consolidated the Murphy’s lawsuit with two other pending cases by the owners of One Eleven Wines in New Brunswick and Val’s Bar in Atlantic City, generating the case name.) Finally, this anniversary reminds us of the sheer perversity of a legal regime in which undercover agents of the state tried to “decode” homosexuality by means that read as laughably clumsy to us now, but were quite harmful at the time.

As in most states, the liquor regulatory agency that emerged in the 1930s after the repeal of Prohibition became a crucial means for state suppression of LGBTQ New Jerseyans. Scrounging in the records of the New Jersey Alcoholic Beverage Control commission (known as “ABC”), one encounters reductive language and ideas about gay people that seem silly today. If a government spy saw a bartender serving drinks to a man who “wiggled his hips as he walked” while “bouncing on his toes,” or two men who “had eyebrow pencil on,” the agency used this information to harass the bar’s owners or even shut it down. Such tactics were part of an oppressive regime that needed ways of discerning homosexuals in the wild in order to excise them from the dominant straight world.

In One Eleven Wines, the New Jersey Supreme Court ultimately ruled that although perhaps in the 1930s it had been unclear whether effective “control” of bars and clubs necessarily entailed keeping out gay men and lesbians, society had matured since then. “Now, in the 1960s,” the justices wrote, the assumption that the state must kick gay people out of bars “is long past,” having yielded instead to what it called “current understandings and concepts.” The court ordered the ABC to “deal effectively with the matter through lesser regulations which do not impair the rights of well-behaved apparent homosexuals to patronize and meet in licensed premises.”

This historic ruling emerged out of a struggle, under the surface of the post-World War II Ozzie-and-Harriet era, when America’s gay establishments were constantly under surveillance by employees of the state dressed up as patrons. Because what historian Margot Canaday calls the “straight state” depended on note-taking by these faux customers, we have a remarkable record of gay nightlife in cities including Newark.

Straight Spies in Gay Newark

Murphy’s was already a thriving queer scene by the time the ABC launched an “extensive investigation” between May and July of 1950. Undercover agents posing as patrons took notes on the regulars, reporting back that they “were openly conducting themselves in a most peculiar and effeminate manner.” According to these spies, homosexuals in 1950 were men who “talked and laughed in high pitched voice; walked in a manner most effeminate (sometimes on tip-toes, sometimes with a ‘wiggle’).” Their conversation around the bar occurred “in the jargon of sexual perverts,” the men addressed one another in feminine nicknames, and “one even used mascara and powder.” They joked about sexual assignations and about male pregnancy. In fact, “patrons were seen to use their hands freely on each other,” with some even going “so far as to fondle the buttocks and privates of other males.” For allowing all this, Murphy’s Tavern had its liquor license temporarily revoked.

Murphy’s location in the heart of downtown Newark, almost around the corner from ABC headquarters, may have put it under special scrutiny. The bartenders at Murphy’s claimed ignorance of the purported perversion in their midst, but the Newark police had warned them three times that summer about the homosexual presence, so their feigned ignorance fell flat. Murphy’s Tavern was clearly, unambiguously serving a thriving scene of gay men.

A decade later in 1961, ABC agents were still spying on gay men in another Newark bar, the Hub, just down the block from Murphy’s. This time, they had to grasp a bit more to articulate the essence of homosexuality, reporting, “males appeared to be homosexuals, as evidenced by their high-pitched voices, their effeminate walk, attire, and mannerisms, which sexual deviation they further displayed by addressing each other as ‘honey,’ ‘sweety,’ and ‘baby.’” While these agents documented none of the expressions of physical desire and affection from the earlier report, they did write up the presence of Francie, “a ‘male’ known as the Belle of Mulberry Street,” who invited unspecified “perverted acts.” For that, the Hub’s license was suspended for 95 days.

Queeny gay men weren’t the only deviates the ABC was worried about. At the Latin Quarter, a bar just south of downtown, ABC agents noted the presence of women who “wore dungarees and male-type shirts and had no facial make-up,” and occasionally “placed their arms around each other’s waist or shoulder.” Again, inspectors tried to prove their case by showing bartender awareness of serving lesbians. As if anticipating Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous inability to define pornography, and as if to call into question the state agents’ own predilections, a server named Louis Anderson quipped back, “Do you know one when you see it?” Yet, the ABC believed it did, and the Latin Quarter’s license was suspended for 45 days in February 1962.

What Makes a Bar Gay?

This same spree of surveillance at the turn of the 1960s—which coincided with antigay crackdowns in other U.S. cities, including New York and Chicago—eventually led to the 1967 victory in One Eleven Wines. The ABC had again suspended Murphy’s’ license for sixty days after more surveillance. In June 1961, the tavern challenged the order in a New Jersey court.

The ABC had two separate charges in the case: first, that Murphy’s had “allowed, permitted and suffered thereon persons, males impersonating females, who appeared to be homosexuals,” which in and of itself constituted a public nuisance; and second, that some of these homosexuals had engaged in “foul, filthy and obscene conduct” while making arrangements for “acts of perverted sexual relations.” Murphy’s countered that the inspectors had merely demonstrated that “persons with effeminate characteristics may have frequented the premises.” The stage was set for an interpretive showdown: How does the state identify a homosexual?

Yet again, ABC agents offered a litany of unmasculine behavior and demeanor: “feminine actions and mannerisms,” eye-rolling and simulated kisses, and, as unnamed Investigator R. insisted, “We could definitely smell the odor of perfume on the premises.” Ever subtle, a somewhat shaken agent R., after witnessing some grabbing of buttocks and private parts in the line to restroom, sighed to a bartender, “The kids must have really been dressed up for Halloween.” After a group of apparent homosexuals kissed the bartender on the cheek and grabbed at his genital area on their way out the door, R., accompanied by fellow agent S., confronted him, asking if that behavior was normal. The bartender shrugged, “That’s nothing … you could see that in any straight bar too.” Taking their commitment to hetero norms one step further, the agents asked if he would kiss them, too. “Sure, if you were my cousin,” he responded.

Out of this awkward encounter, legal history was made. Murphy’s presented witnesses in its defense, such as local man William R. Peters, a regular patron who testified that while some of the customers “have fairly high voices,” he remained unperturbed by them and “did not perceive any homosexuals.” A bartender “conceded that some of the patrons had feminine characteristics but denied that any of them, to his knowledge, were homosexuals,” explaining their “possible touching” through the crowdedness of the bar. He denied knowing what “fag” or “fairy” meant. They even brought in an athletic director from the Newark Athletic Club, who told the court it was “not possible to tell from a person’s mannerisms whether he is a homosexual.”

But in the end, none of it mattered. While the court assured that it was not “callous to the problem of the homosexual,” it found abundant evidence that “an inordinate number of the patrons habitually congregating at the tavern displayed the dress, mannerisms, speech, and gestures commonly associated with homosexuals.” And since its primary concern was “maintenance of accepted standards of public decency and morality,” the ABC prevailed—for a time.

Toward a Queer Legal Milestone

In the end, however, Murphy’s Tavern fought back, and won. The bar continued in business while appealing its case, which sat in the legal system until being combined with similar cases from New Brunswick and Atlantic City. In this next round, the key issue had to do with the meaning of the word “apparent.” An ABC spokesman explained that the agency employed this term “because they behave as homosexuals and act as homosexuals. But it is not because they are homosexuals (that the licenses were suspended). If they were just sitting there, there would be no disciplinary procedures.” He emphasized that “in every case there was activity — males dancing together, kissing, embracing. These are overt acts.” The ABC had lewdness and immorality charges at its disposal, but the legal question had shifted to the more general nuisance category; the convoluted effort to construct the “apparent homosexuals,” a group defined through both action and affect, attempted to blur that legal distinction.

When the New Jersey Supreme Court finally issued a decision in Nov. 1967, it was a stinging rebuke to the ABC. The pioneering homophile group the Mattachine Society had filed a brief in support of the bars, and Dr. Wardell Pomeroy from the Kinsey Institute also testified, but ultimately the decision was a referendum on ABC tactics. Regarding the state’s claim that “the presence of apparent homosexuals in so-called ‘gay’ bars may serve to harm the occasional non-homosexual patrons who happen to stray there,” the court simply scoffed. The ABC also argued that “offensive conduct” by gay patrons might lead to violence against them, and even asserted the need to “increase public respect and confidence in the liquor industry” through its policing, but to no avail. While insistently repeating the phrase “apparent homosexuals” in its opinion, the court even jabbed at the misapprehensions of the ABC investigators, noting that they repeatedly conflated these figures with female impersonators, “although that term relates more properly to transvestites who are, for the most part said to be non-homosexuals.” In other words, the court did not accept that the ABC spies could tell, just by looking and listening, whether a bar patron was gay. Not only couldn’t the state get its apparent homosexuals straight, perhaps some of them were in fact straight!

The One Eleven case was a major breakthrough in New Jersey, even though the court hinted that, had the ABC been cleverer in pursuing specific lewdness or immorality charges against Murphy’s rather than the more general nuisance, it might have won. The head of the Newark police department, Dominick Spina, bemoaned the decision, suggesting that only police repression had “saved” Newark from devolving into a “Greenwich Village or hippie land.”

Thus, a key right—to gather unmolested by the state—was won for the gay people of Newark, and New Jersey, even though the court left open the possibility of moving backward in the future, should “apparent” homosexuality slide too far into actual physical contact in a bar. This was not the explosive eruption of the Stonewall rebellion, which signaled a more militant phase in the history of LGBTQ activism. Instead, this was a hard-won toehold, a tenuous gain, waged by bar owners, and an insecure new right—which is, indeed, primarily how queer freedoms have expanded both before and after Stonewall.

Murphy’s itself, it’s important to note, was not always a utopia for LGBTQ people. Interviews by the Queer Newark Oral History Project at Rutgers University-Newark reveal that its patrons in the 1950s were mostly white, but grew increasingly multiracial by the 1970s, when Newark had become a majority-black city. Yet Murphy’s still sometimes clung to its own exclusionary vision of apparent homosexuality. Miss Pucci Revlon, a Newark transgender pioneer, recently recalled being turned away at the door of Murphy’s, she believed because the proprietors didn’t want trans folks inside—although in time, the bar grew more hospitable. For decades, it served a central role in local LGBTQ communities; as Puerto Rican lesbian Yvonne Hernandez puts it, “I felt safe there.” As late as 2003, Out magazine called it a “laid-back neighborhood gay pub.”

For many decades, Murphy’s was a haven for LGBTQ people in the heart of Newark. Like so many historic LGBTQ establishments across the country that survived decades of police harassment, ultimately the place was demolished by developers, to make way for the Prudential Center sports arena that opened in 2007. Today, the block where it once stood is a barren slab of concrete. Instead of any historical marker to the landmark of gay history, like the Stonewall Inn just across the Hudson river, it is graced instead with a gigantic statue of a hockey player. Not all physical sites of LGBTQ history can be National Monuments, of course; but as the landscapes of our cities change, it’s worth remembering the many dives, cafeterias, and other unlikely spaces where the gradual, hard-won early steps towards equality took place.