When I started college at Tufts University 30 years ago this fall, my active sex life was a mere two months old and included just two partners. Early in my first semester, in the tiny library in our campus gay group’s cramped office on the third floor of an unmarked clapboard house, I found The Joy of Gay Sex, which Edmund White co-authored with Dr. Charles Silverstein a decade earlier, in 1977. Too nervous to take it back to my dorm, I sat on a rump-sprung sofa behind the office’s closed doors and nervously flipped through the pages. Although the book was only 10 years old, it already seemed like a document from a distant age.

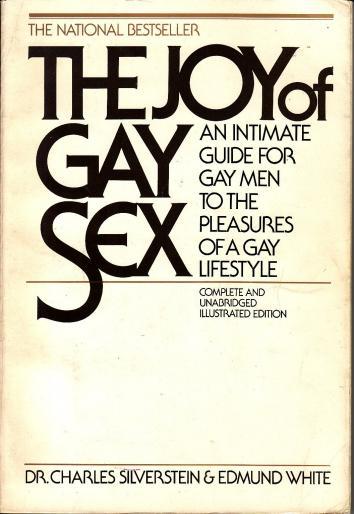

Harper Collins/Amazon

AIDS had hit the headlines several years earlier, when I was starting junior high, so I’d never thought or even fantasized about sex in a way that didn’t involve risk—constantly looming, often unknowable, potentially fatal. But because The Joy of Gay Sex was published before the epidemic began, it didn’t contain any of the specific information about HIV or condoms or safe sex I urgently needed to overcome my ignorance and anxiety in such a toxic time.

Despite such unavoidable omissions, the book nonetheless communicated a simple message that made an enormous impact on me as a horny but terrified teenager: that sex, including (or perhaps especially) gay sex, was about joy. This theme—daring in the seventies, downright revolutionary in the eighties—flows implicitly through the book’s frank and shame-free prose, and surfaces explicitly at several points in case readers might otherwise miss it. For instance, from the introduction: “Sex is one of life’s chief pleasures.”

As a 16-year old who’d followed my first, quite tame sexual experience that summer by dragging my then-boyfriend to a clinic for an HIV test—the two-week waiting period for results turning into an extended panic attack—I had never framed my desires in such unambiguously upbeat terms. It took a while to get past the fear, the second-guessing, the sense of doom with every encounter; but reading The Joy of Gay Sex helped me focus on the sheer bliss of it all, the ecstatic thrill of sex. And that allowed me to grow into the safer, saner, happier gay man I am today.

* * *

Rereading the first edition of the book now, 40 years after its publication, I am still impressed by its sex-positive tone—no less radical today. But now that my active sex life stretches back decades and includes, well, far more than two partners, I’m surprised to find that while the book deeply influenced how I continue to feel about my sexuality broadly speaking, it doesn’t particularly connect to the actual sex I’ve had since I read it in college.

“The gay sexual repertoire may thrill you or repel you or just bewilder you,” White and Silverstein explain. And true enough, the acts that they catalogued in alphabetical order in The Joy of Gay Sex seem reasonably wide-ranging. Some are things the authors clearly enjoyed, like rimming (“a prime taste treat”) and threesomes (“a way for lovers to add spice to home cooking”); others they included despite apparent disdain, such as fisting (“extremely dangerous”) or watersports (“what is the appeal of piss?”). But it’s immediately clear that these menu items are thrown in as optional sides for the single main dish of gay male sex—fucking. White and Silverstein can’t stop waxing lyrical about the many positions in which one man can fuck another, each getting its own rapturous section with a catchy name: Bottoms Up, Crab, Doggy Style, Face to Face, Scissors, Side by Side, Stand Up and Take a Bow, Topping It Off.

Even the vaguely titled First Time is not about the first time a man has any kind of sex with another man, but specifically the first time a man gets fucked—as if bottoming were the thing that defines a gay man’s “first time,” the only act that really counts. Considering how frequently gay men’s sex lives are presented elsewhere in the book as distinct from straights’ (and how gay sexuality, in the authors’ estimation, threatens the very foundations of straight society), putting so much emphasis on fucking as the central act, the one all other acts ultimately lead to or else conspicuously avoid, seems awfully heteronormative.

For a cocksucker like me who’s never evinced any particular interest in fucking, White and Silverstein have little to say. The entry on Blow Jobs gets less than one page—less space than they devote to Camping (as in humor, not as in tents)—and even that brief bit describes the act that has driven my erotic desires since my memory began as merely “a prelude to the full symphony of intercourse.” Their tips on technique are cursory and unremarkable: “Use your hand as an extension to your mouth.” (I got more detailed advice from my sister’s Cosmopolitan.) Oral sex warrants just one more entry: Sixty-nining. And here, too, the authors sound bored and confused: “Few people have much to say in favor of sixty-nining save as a variant to more usual fare, or as a first or second course in a long erotic supper.” Never the last course, or even the whole meal?

I try to imagine how I might have written this book differently. In my head, I tally how many positions for oral sex I can conjure, and what catchy names I might give them: Open Wide and Say Aaaah, Kneeling at the Altar, Hang Your Head, Lie Back and Think of England. Would entries like those have spoken more directly to my younger self? At 16, I had just discovered my nipples; White and Silverstein were mum on the subject. There’s also no mention of phone sex, which consumed so much of my cash in college, ten-cents-a-minute (twenty-cents-for-the-first) at a time. Or personal ads, the old-fashioned kind in the classified section of the newspaper, which is how I met my first boyfriend, as well as the man who’d eventually become my husband.

Yet while it’s easy enough to list the things that are “missing” from The Joy of Gay Sex, I can also name many things I’m glad White and Silverstein included. The book serves, in part, as a quite specific how-to guide for certain situations that otherwise might be baffling at first glance, including bathhouses (“for sheer efficiency, the baths can’t be bettered”), public bathrooms (“the etiquette of tearoom sex is elaborate and codified”), and cruise bars (“the signals are as elaborate and subtle as the movements in the Japanese kabuki”). Here, the authors are at their most practical; I wish more men today would read their simple instructions, and carry them on crib notes in their pockets. It would save so much time and aggravation.

The book is even more essential for discussing subjects that some might (wrongly) consider separate from sex: alcohol, drugs, depression, emotional problems, guilt—issues that Silverman, a psychologist and sex therapist who had been instrumental in getting the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses in 1973, had surely seen his patients wrestle with. Coming out gets a hefty 10 pages, and gay liberation and politics are presented as inherently connected to desire.

But most of all, The Joy of Gay Sex remains important as an antidote to shame; the authors discuss risks, downsides, dysfunction, illness—but never in a way intended to stop readers from exploring and enjoying their sexuality. No judgments when discussing orgies—only the comment that “organizing them is the hardest part.” A thorough dismissal of the entire concept of promiscuity: “It is a word that makes little sense in gay life.” And a clear stance on fidelity and monogamy—“they are not necessarily the same thing”—that many gay men would be wise to remember in this age of same-sex marriage (and divorce).

There’s a sense of excitement that pervades the book, as the writers envision (and help delineate) a sexual community of like-minded souls—one with a shared past, present, and future. The authors’ history of homosexuality and modern gay identity, described so eloquently in the introduction, is truly stirring. “Modern gay life has no antecedents,” the authors write, as they leap through pre-modern precursors by touching on everyone from Plato to Oscar Wilde. Then, drawing on examples from Michel Foucault to Batman and Robin in their discourse on contemporary sexual politics and masculinity, they boldly proclaim: “The modern homosexual is free to become the man he wants to be.”

* * *

While AIDS, unknown in 1977, is not in the book, it does cover other venereal diseases. (Gonorrhea, the first edition explained, was “the major health problem of male homosexuals.”) The authors were criticized nonetheless when the epidemic struck a few years later. “The idea that we’d erred somehow in not foreseeing an unprecedented disease no scientist in the world had predicted strikes me as a bizarre and unfair,” White recounts in his 2009 memoir City Boy. “The publisher certainly made a mistake, however, in not withdrawing the book immediately and replacing it with an AIDS-conscious edition.”

The authors believed that a revised edition would not only be more useful in the bedroom, but might actually save lives, as Silverstein recalls in his 2011 memoir For the Ferryman: “By the late 1980s, the AIDS epidemic had already killed tens of thousands of gay men. The original Joy of Gay Sex was out of print and I thought that a new edition … might influence young gay men to avoid unsafe sex.” Due to issues with the publisher, however, a revised edition would ultimately take 15 years to be published.

When The New Joy of Gay Sex finally came out in 1992—including entries about HIV and safer sex, not to mention nipples and phone sex—Felice Picano took over as Silverstein’s co-author, but White wrote the preface for the new edition. By this point, he was already a prominent gay author, having published his acclaimed novels A Boy’s Own Story and The Beautiful Room is Empty, as well as the gay cultural travelogue States of Desire. But that hadn’t been the case when he wrote The Joy of Gay Sex in 1977; at that point, he had just one novel (Forgetting Elena) to his credit, and coming out as a gay writer bore its own risks. As he reveals in the preface to The New Joy of Gay Sex, he had considered using a pen name before ultimately rejecting that notion. In keeping with the liberated spirit of the book: “I discovered that signing it was the most liberating act of my life, the first time I identified myself as a proud homosexual. At the time I was sort of whistling in the dark, but I was the first to be convinced by the cheerful, confident tone of our own words.”

White was being modest. He didn’t merely identify himself as gay by putting his real name on The Joy of Gay Sex in 1977. He outed himself as a sexually active gay man. “An endless round of one-night stands or short affairs can provide a gay man in a big city with constant novelty and excitement and introduce him to a wide variety of erotic delights,” the original introduction explains, before adding a more personal aside: “And these delights can be deeply rewarding.” Lest there be any question about which author was speaking, the volume’s dedication says it all: “To all my tricks, from Ed.”

Readers never knew how difficult it had been for White to appear so carefree and comfortable, until he reflected on co-authoring The Joy of Gay Sex years later in City Boy: “My own problems in dealing with being gay were crippling—I’d devoted decades in therapy to coping with them and as a teenager had often been suicidal. But in our sex manual I decided to take a jaunty, relaxed tone, to ‘act ahead of my emotions,’ as a friend undergoing therapy put it.”

By deliberately presenting himself utterly at ease with sex in general, and his own sex life in particular, White helped me (and, I’m sure, thousands of others) separate desire from shame. He presented a gay world with a shared sense of history and politics as well as eroticism, a community that was fundamentally decent and responsible as well as playful. He may not have truly believed it himself in 1977, but he helped me believe it as I came out a decade later. And I still believe it today.