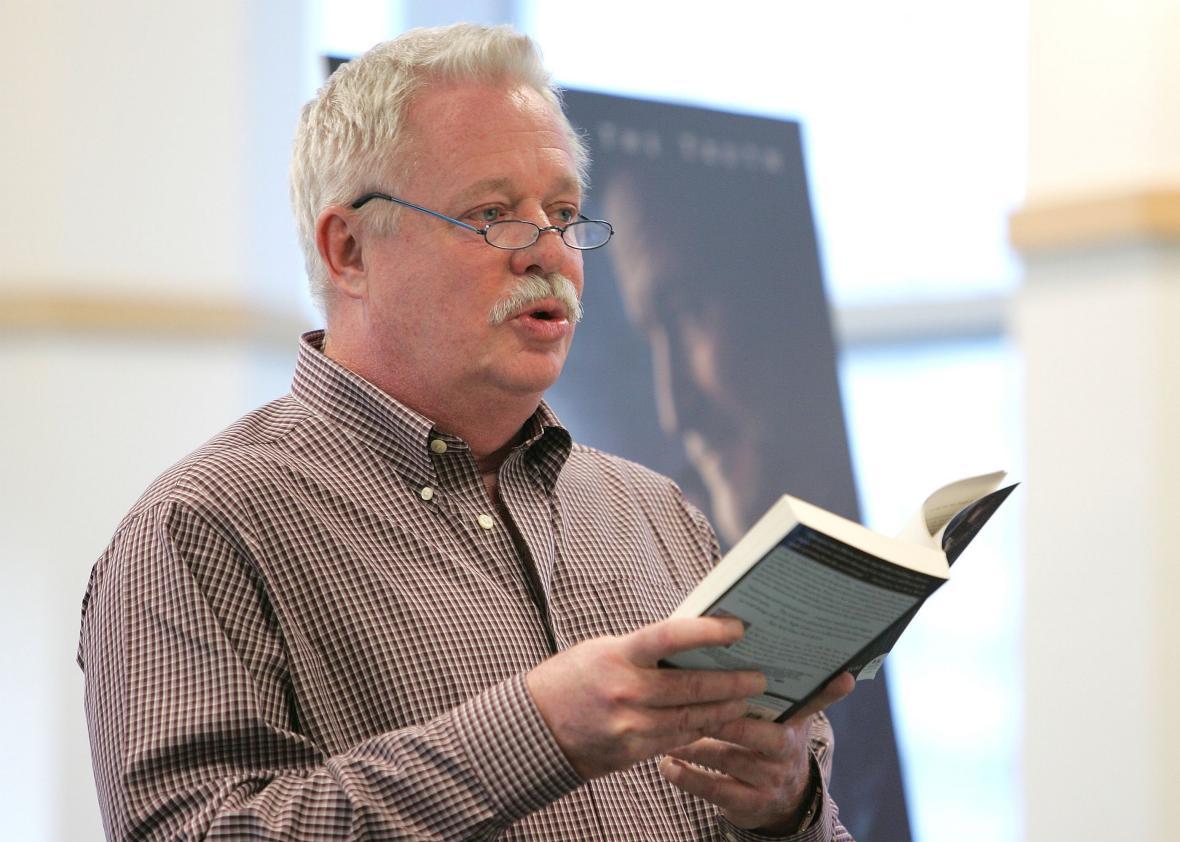

Growing up in the 1950s and ’60s in North Carolina, the novelist Armistead Maupin was a gentle, fanciful child who feared the mandatory dodgeball game at recess and convinced his parents to outfit his bedroom with a stained-glass window. His father, a lawyer who romanced racism and was prone to bouts of unexplained rage, assumed his son would grow out of his delicate constitution. Sensing early on that keeping up appearances was vital to survival, and longing unrequitedly for his father’s love across much of his life, Maupin initially tried to fit in: He embraced conservative politics, worked at a television station then managed by future U.S. senator and rabid social conservative Jesse Helms, and served in the Navy during the Vietnam War.

Lucky for his readers, Maupin ultimately made his way to San Francisco as a newspaper reporter. It is there that he channeled his sensitivity and sense of wonderment—as well as the self-discovery of being gay—into a groundbreaking newspaper serial that served as the foundation for his now-famed Tales of the City novels. The nine-book series chronicles a core of mysterious and at times rather randy inhabitants of San Francisco from the mid-’70s through to this decade, in the process addressing such taboo subjects for their eras as gay sex, AIDS, and transgender identity.

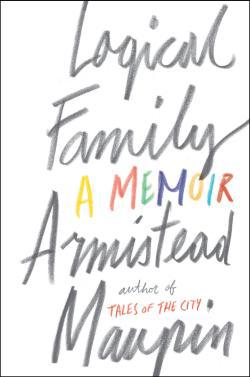

“How could I have guessed then that the thing I feared most in myself would one day be the source of my greatest joy, the inspiration for my life’s work,” Maupin writes early on in his new memoir, Logical Family. In it, as its title suggests, Maupin earnestly conveys a process painfully familiar to many LGBTQ people—that of harnessing the love, acceptance, and magic of people they meet who are kindred souls, if not blood relatives—and forming their own tribes. For Maupin, this has included a rather colorful cast of characters over his 73 years, from the hippies he encountered living on a mountaintop in Vietnam; to the closeted movie star Rock Hudson and the circle of queers who surrounded him, keeping his sexuality and AIDS diagnosis a secret; to his friend actor Ian McKellen, whom Maupin convinced to come out in 1988.

Harper Collins Publishers

“In terms of the torture we endure when we’re young, I think many of us have been through the same things,” Maupin recently told me by phone from his apartment in San Francisco. “One of the reasons I wrote the memoir was to get over the fact that I was cross with myself for having waited so long to come out.”

Maupin was 30 when he penned the trenchant “Letter to Mama,” a way for Michael Tolliver, one of his characters in the Tales of the City newspaper serial, to come out to his family. Maupin’s parents followed the Tales series, which was printed in the San Francisco Chronicle, and he knew in reading it that they would understand that Maupin, too, was gay. As Logical Family reveals, his father wrote him a terse note in the aftermath, advising him not to upset his mother, who had been diagnosed with breast cancer. The elder Armistead never acknowledged the open-hearted message of his son’s missive: “If you and Papa are responsible for the way I am, then I thank you with all my heart, for it’s the light of my life.”

Maupin nevertheless credits “Letter to Mama” as being one of his greatest achievements; indeed, it has been so embraced by the LGBTQ community that it has since been set to music by the composer David Maddux and performed in gay choruses around the world. So universal is its sentiment and prose that readers have written to Maupin, recalling that they cut the letter out of the Chronicle in 1976, crossed out the name “Michael,” inserted their own name, and sent it to their parents.

For Maupin’s part, the entrenched homophobia of his own youth lives on in his family’s conservatism. Donald Trump’s ascendance to the White House has only reinforced the division, which he said often asserts itself on Facebook. “I have virtually divorced the remaining members of my biological family because of their insistence that their support for the Republican Party in no way affects their love for me.” By way of example, Maupin says his father continued to vote for and revere Helms, the racist homophobe, until Helms’ death in 2008. Of his brother, who voted for Trump, Maupin says, “He’s locked into a worldview that he thinks is his birthright, and he’s welcome to it.”

Logical Family gives selflessly of such heartrending experience as it journeys through Maupin’s life. In learning of his bone-chilling fear of being found out as gay as a child, in college, and in the Navy, younger readers will understand that shouting “We’re here, we’re queer” was at one time simply unimaginable, if now only sometimes perilous. Likewise, the memoir puts it stark relief how AIDS decimated circles of friends and communities long before the advent of any medicines that made it the livable chronic condition it has become for those with access to treatment.

Simultaneously, the memoir also lays bare the blessings in Maupin’s life, in particular, the presence of steely, unconventional women. His mother quietly and rather regally contested her husband’s stridency where she could. His grandmother, a suffragist in her native England, was more overt. Maupin describes his “Grannie” vividly in the memoir, in particular recalling a moment at age 14 when the two attended a garden party. A perfumed and powdered woman tottered by them in heels. Once she was out of earshot, Grannie opined, “Any woman who is all woman or any man who is all man is a complete monster unfit for human company.”

Maupin credits such wisdom as making a huge difference in his life. “I was blessed with a lot of wonderful old ladies when I was growing up, and I think that’s why I ended up creating a wonderful old lady, Anna Madrigal,” he says of the centerpiece character of his Tales series.

Fans will surely be gratified to know that Tales, which in the past aired as a ground-breaking television series on PBS, will again receive such treatment by Netflix, which has signed on for 10 installments. Maupin reveals that the episodes will take place in present times, with beloved character Mary Ann Singleton, played by Laura Linney, returning, now at 53. Other stars will reprise their roles, including Olympia Dukakis as Madrigal and Paul Gross as Brian Hawkins.

“There are rumors that Ellen Page will play Shawna. I couldn’t be more excited about that,” says Maupin of the role of Hawkins’ bisexual daughter.

But Maupin has not only created screen fodder—he’s also the subject of it in a new documentary about his life, The Untold Tales of Armistead Maupin, which will air on PBS in January. Despite all this attention and obvious success, Maupin can only say, “There’s nothing particularly special about my life.”

His memoir betrays that contention over and over, but most impactfully in the way it closes, with the full rendering of “Letter to Mama,” and the story of how he read it for the first time all those years ago in the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. “An unnerving silence settled over the room when I was done. It took me a while to realize that people were crying.” Maupin collapsed in his seat, whereupon, “I felt the laying-on-of-hands, dozens of my brothers and sisters touching me in benediction.”

Update, Oct. 5, 2017: This post was updated to include the name of the composer who set “Letter to Mama” to music.