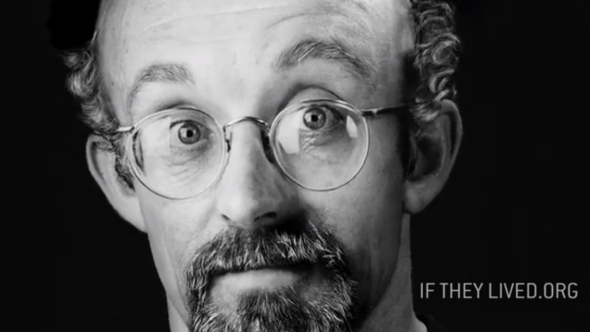

If they had lived, who would we be? That’s the question driving the Father’s Project, a crowdfunded video-based art project by the Mexican activist and filmmaker Leo Herrera. When we think about the HIV/AIDS epidemic and its impact on the LGBTQ community, it’s easy to focus on the numbers of lives lost, especially at the height of the dying in the 1980s and early ’90s. But those deaths also took with them a generation’s worth of knowledge and creative potential, leaving the next generation poorer, searching for role models and cheated of their rightful queer cultural inheritance. Herrera and his collaborators’ project takes the daring leap of imagining that this void never formed in the first place, that our “fathers” lived long and productive lives and that queer culture remained an incubator of innovation rather than a site of incomprehensible tragedy.

Because Herrera is currently at work on the project, we don’t yet know exactly what this “queer utopia,” as he calls it, will look like, but the tone is something akin to “Cruising meets Black Mirror meets Beyoncé’s Lemonade.” I emailed with Herrera about his aims and process as he was en route to film in Provincetown, Massachusetts—a fine example of what he calls queer people’s talent for “carving utopias” if there ever was one.

You’ve described the Father’s Project as a sci-fi–like imagining of what the world would look like if the AIDS crisis had never happened, particularly in terms of if a generation of queer men hadn’t been cut in half. What was lost with them, beyond life?

HIV has been immensely greedy in what it’s taken from us. We’ll never measure the loss of ideas in art, science, and politics from the height of the epidemic to today, where it continues to bleed us of resources and lives, especially in communities of color. The loss is truly unfathomable.

How did you first come to feel that loss in your own life and work?

If AIDS was our Hiroshima, then its aftermath mutated generations to come. I’ve seen friends self-destruct after sero-converting, and the stigma does damage we still don’t fully understand. Anyone who’s felt the inherent confusion of being LGBTQ has felt the loss from AIDS. The folks who died took with them stories and life lessons that could guide us today. Instead, we have a huge generational gap and so many questions of who we’re “supposed” to be.

What sorts of stories or figures are you featuring in the film? Why did you choose specific ones, such as leather men?

The first wave of queers were both captains and infantry. The trans women of color who started riots, those who flaunted their sexuality through leather, or who broke away from gender norms by building Radical Faerie sanctuaries were hit the hardest. Digging for these stories through research of living and dead folks is the driving engine of my creative process.

Studying queer history has this way of making one feel like we are repeating ourselves—the same kinds of debates over inclusivity, assimilation, and terminology, for example, have been cycling since the 1950s, if not earlier. I know you often complain on social media about queer infighting: Do you see the Father’s Project as some kind of corrective for that cultural amnesia?

Fathers isn’t here to correct, but to remind and educate about what was and is still possible. Our infighting comes from a deep insecurity about our place in the world and while Fathers doesn’t shy away from the darkness of our culture, it’s really about resilience and the healing power of listening to one another’s stories.

Tell me about your creative process: Who are you collaborating with? What kind of research are you doing to inform the work?

The same diversity we apply to the dead, we apply to the living. We’re reaching out to established artists, like Justin Vivian Bond and Jake Shears, but also to emerging queer artists of color, like Franky Canga from New Orleans, or Banjee Report from Brooklyn. Our research spans the California Historical Society to the Leather Archives in Chicago to Visual AIDS and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York.

Edmund White has written, in effect, that AIDS took the most interesting queer people and left us with “dull normals” (many previously closeted) who then took over the mainstream movement and culture. What’s your view of the arc of gay history before and after HIV/AIDS?

The optimist in me has to believe the AIDS crisis also made folks blossom. At this very moment, there is a latinx trans woman in Queens putting on her face to go out and educate the children on PrEP … would she still be helping folks if it weren’t for this catastrophe?

Trauma from HIV/AIDS has been invoked a lot recently in discussions around PrEP, barebacking, and a budding return to ’70s sex culture. What role do you think trauma plays in the lives of queers today?

Queer folks have known trauma from the first moment they’re harassed for having too good a time, yet history has proven that we’ve always existed as parade and funeral, of finding joy and sexuality in the darkest of situations. Trauma plays a role in every queer experience, and can propel us to our most powerful selves.

What do you think about the idea that, in a way, the loss, anger, and grief of the first decades of the AIDS crisis were, if not “good,” maybe productive for gays? After all, our greatest activism came out of that era, not to mention profound art and arguably the paradigm of visibility/outness we live in today. Is erasing that, tempting as it might be, really something we should want?

Fathers is about the complex questions every culture deals with. Were Jewish people strengthened by the Holocaust? Will Mexican and Middle Eastern immigrants thrive through the trauma of our current America? Do I think putting up with bullshit strengthens a culture? Absolutely. The ways in which it does so is what this project is about.

Is there one value or lesson that you think queers need today that the Father’s Project could help restore?

We’re currently filming scenes of joy and celebration all across America for our gay president storyline and if there’s a lesson in this process it’s that queer people are masters at carving utopias, no matter how unwelcoming the terrain. I’d like Fathers to remind folks that these ideals of acceptance and love of a chosen family are our legacy.

You can support the Father’s Project by donating directly. Donations are tax deductible and benefit the GLBT Historical Society and Museum in San Francisco.