Shortly after Robert Huskey died at the age of 86, his husband and partner of 52 years received some shocking news: The Mississippi funeral home that they had paid to transport and cremate Huskey’s body now refused to do so—simply because he was gay.

That’s the allegation laid out in a lawsuit brought on behalf of Huskey’s husband, Jack Zawadski, as well as his nephew, John Gaspari, against Picayune Funeral Home. On Tuesday, Lambda Legal joined the suit, which seeks damages for breach of contract, negligent misrepresentation, and the intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress. Zawadski and Gaspari aren’t suing the funeral home for engaging in anti-gay discrimination because Mississippi does not protect LGBTQ people from refusal of service. Indeed, the state’s notorious HB 1523 actually protects businesses’ right to turn away LGBTQ customers—though the courts have put that law on hold for now.

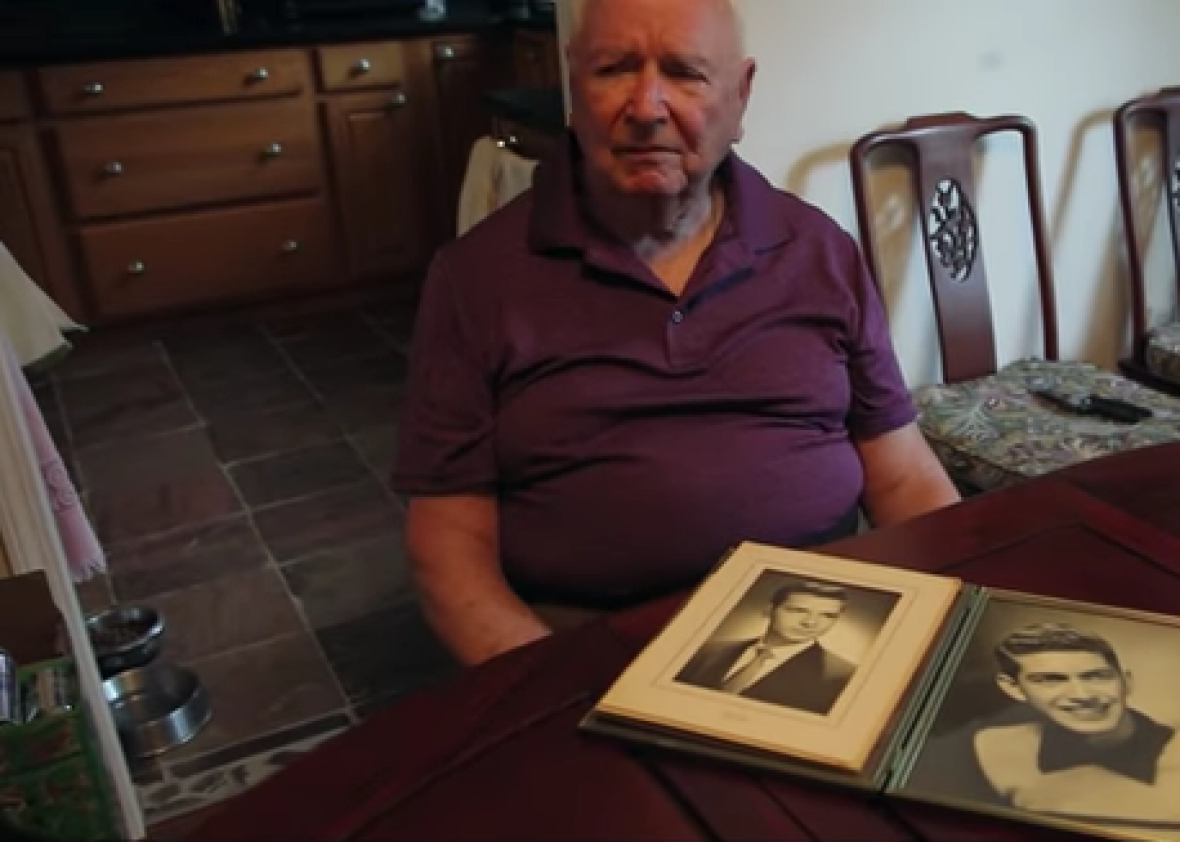

The story laid out in Zawadski and Gaspari’s lawsuit is a heartbreaking one. Huskey met Zawadski in 1965, and the two quickly fell in love. They moved around the country together to care for family members, tend to an apple farm, and teach special education, finally retiring in Mississippi in 1997. After the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry in 2015, Huskey and Zawadski wed. Huskey, however, suffered from a heart condition, requiring his husband to provide round-the-clock care. In the spring of 2016, it became clear that Huskey would soon die. The couple’s beloved nephew, Gaspari, helped Zawadski locate a nursing home to help Huskey in his last weeks, in addition to a funeral home to cremate his body after death.

Initially, the nearby Picayune Funeral Home seemed like a perfect choice, and Gaspari agreed to pay the company $1,795 to transport and cremate Huskey’s body once he passed. But when Huskey died and the nursing home contacted the funeral home to pick up his body, it refused to do so. The funeral home had discovered that Huskey’s next-of-kin was his husband, and realizing Huskey was gay, informed the nursing home that it did not “deal with their kind.”

Zawadski and Gaspari were mired in grief and pain—but they had to scramble to make other plans: The nursing home had no morgue, so Huskey’s body had to be moved immediately. The closest suitable funeral home with an on-site crematorium was in Hattiesburg, 90 miles away. Zawadski and Gaspari therefore had to locate a closer funeral home to transport Huskey’s body from the nursing home to Hattiesburg. The resulting chaos and confusion thwarted their plans to gather friends in the community to honor Huskey.

In a more progressive state, Zawadski and Gaspari could have sued Picayune Funeral Home for discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or filed a complaint with the government, which could then sanction the Picayune Funeral Home and force it to stop discriminating. But because Mississippi law does not prohibit anti-LGBTQ discrimination, Zawadski and Gaspari could only sue for breach of contract, in addition to several tort claims. They cannot demand that the funeral home stop discriminating against LGBTQ customers. And if Picayune Funeral Home had rejected their request before assenting to the contract, they might not have been able to sue at all.

Even worse, there is a possibility that the courts will have to throw out Zawadski and Gaspari’s lawsuit altogether. In the name of “religious freedom,” HB 1523 allows businesses to refuse “to provide services, accommodations, facilities, goods or privileges” to gay people out of a belief that marriage “should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman.” The law explicitly bars any arm of the state government—including state courts—from imposing a “monetary penalty” upon a business for declining to serve gay people. This rule applies “in any judicial proceeding,” including those brought by a “private person.” The upshot is that Picayune Funeral Home could almost certainly use HB 1523 as an absolute shield against this lawsuit.

At the moment, though, it cannot, because U.S. District Judge Carlton W. Reeves enjoined the law for unconstitutionally favoring certain religious beliefs while demeaning others. But Republican Gov. Phil Bryant appealed that ruling, and in April, a panel of judges of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals indicated that it might lift the injunction. If it does—and the Supreme Court does not step in—Picayune Funeral Home may well raise HB 1523 as a defense. And at that point, the law’s defenders will no longer be able to deny that their bill represents little more than vicious, bigoted cruelty wrapped in the vulgar pretext of religious liberty.