At the 1992 Academy Awards, where The Silence of the Lambs would become only the third movie ever to sweep five coveted Oscar categories, the focus wasn’t inside the theater. It was on the protestors outside. Breathless reports that gay groups like Queer Nation and ACT-UP had infiltrated the production and would disrupt the ceremony with “some sort of guerrilla tactic” were the talk of Hollywood. Hundreds of people gathered outside for the culmination of a year’s worth of protests against the depiction of Jame Gumb/Buffalo Bill, the flamboyant killer tracked by Clarice Starling. Organizers demanded the industry depict regular gay lives, not lunatics with yapping poodles. (As one spectacular refrain went, “We’re queer; we’re groovy; put us in your movie.”) A nervous Hollywood reacted by wearing red ribbons for AIDS victims.

Jonathan Demme, who died this week at 73, was favored to take best director that night for Silence of the Lambs. His only competition was dark horse Oliver Stone, for JFK; the gays also weren’t happy about that one, because of the whole Tommy Lee Jones bit. The awards capped perhaps the biggest year of Demme’s career, but also one he later described as painful, because he suddenly found himself the target of intense ire from a queer audience with whom he had long considered himself aligned. Though the Oscar ceremony went uninterrupted, and Demme nervously accepted his statuette, the protests still captured much of the press the next morning.

Ever since gay groups had first seen Silence of the Lambs in Los Angeles more than a year before, there had been steady outrage. Although today the objection to the movie has been recast as concerns about transphobia, at the time, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) and gay critics were actually protesting homophobia. “The killer in the movie is a walking, talking gay stereotype,” one GLAAD leader told the press. “He has a poodle named Precious, he sews, he wears a nipple ring, he has an affected feminine voice, and he cross-dresses. He completely promotes homophobia.” They cited a reference to a past male lover. Orion, Lambs’ distributor, attempted to quell the controversy by loaning prints of the movie for AIDS fundraisers, but it did little to calm the uproar.

Screenshot via YouTube

At first, Demme was defiant of the protests. In 1991, he told Film Comment, “We knew it was tremendously important to not have Gumb misinterpreted by the audience as being homosexual. That would be a complete betrayal of the themes of the movie. And a disservice to gay people.” He described the killer as “someone who is so completely, completely horrified by who he is that his desperation to become someone completely other is manifested in his ill-guided attempts at transvestism, and behavior and mannerisms that can be interpreted as gay.” To be fair, Demme is correct—in the movie, Hannibal Lecter posits that Gumb apes queer and trans people because they’re the most outré, far-off identities he can imagine—the ultimate escape. What Demme didn’t quite get at the time is that the finer points of the text can get a little lost when you’re watching a movie about a guy cutting off women’s skin to make himself a real-life costume of female flesh. In 1991, amid a rash of anti-LGBTQ violence, Hollywood continued its parade of gay weaklings, perverts, and killers, and Silence of the Lambs’ visceral depiction became an easy flashpoint.

The protests were a strange turn of events for a director who had long been a sensitive champion of marginalized people and unconventional artists in feature films and documentaries. He repeatedly called the Queer Nation rhetoric “very unfair,” and clearly took it personally. But instead of turning inward, he did a curious thing: He bet his Oscar success on a high-profile movie about a gay lawyer with AIDS, Philadelphia, with megawatt stars Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington to come on board. The movie was a considerable professional risk for him and financial risk for TriStar, but it went on to become a critical and box office success. It is hard to imagine a similar response from a filmmaker at his professional height today, nor a studio willing to risk a future hashtag campaign against a proven enemy of the era’s political order.

Demme’s critics, it’s worth noting, were unmoved. Philadelphia, which got no more gay than chaste same-sex dancing, found angry public detractors in Scott Thompson, the gay Kids in the Hall comedian, and Larry Kramer, the firebrand writer and activist. In a furious Los Angeles Times op-ed, Kramer wrote, “I bring up the painful reminder that Demme also directed The Silence of the Lambs, which many gays consider one of the most virulently and insidiously homophobic films ever made. Is Philadelphia some sort of attempt on his part to offer an apology? After these two films, I wish he’d just go away and leave us alone.”

This idea that Philadelphia was an apologia to atone for Lambs has become part of both movies’ lore. But Demme and his then-producer Edward Saxon both insisted the two movies had nothing to do with each other. “We had wanted to make a movie in which AIDS was a major character before we ever filmed Silence of the Lambs,” Saxon said at the time. As late as 2014, Demme still maintained he wanted to make the movie “because so many of my loved ones were getting sick, including Juan Botas.” (Botas, a Spanish-American artist and a longtime confidant of Demme’s wife, died from AIDS complications in 1992.)

Given the breadth, intimacy, and generosity of Demme’s career, I tend to believe him. And though even now it feels absurd to celebrate a straight director for deigning to take on an AIDS story, it does reflect Demme’s unforced grace that he made the movie despite knowing it was likely to pull him back into an international uproar.

His response to the criticism of Philadelphia also seemed to evolve. “I expected it—actually hoped for it,” he said in 1994. “It’s the job of militants to demand more of anything. If these people were satisfied, change would be hard to get through. Every one of them is right. There could have been more of this, or more of that, but now, maybe another film will take it further.” As the years went on, he also seemed to understand why activists were so incensed by Lambs. “Jame Gumb isn’t gay. And this is my directorial failing in making The Silence of the Lambs—that I didn’t find ways to emphasize the fact that Gumb wasn’t gay,” he said in 2014. “Juan Botas, who was one of the inspirations for Philadelphia, said, ‘You can’t imagine what it’s like to be a 12-year-old gay kid, and you go to the movies all the time and whenever you see a gay character, they’re either a ridiculous comic-relief caricature, or a demented killer. It’s very hard growing up gay and being exposed to all these stereotypes.’ That registered with me in a big way.” He acknowledged, fondly, “It’s now become a part of the dialogue on stereotypical portrayals of gays in movies.”

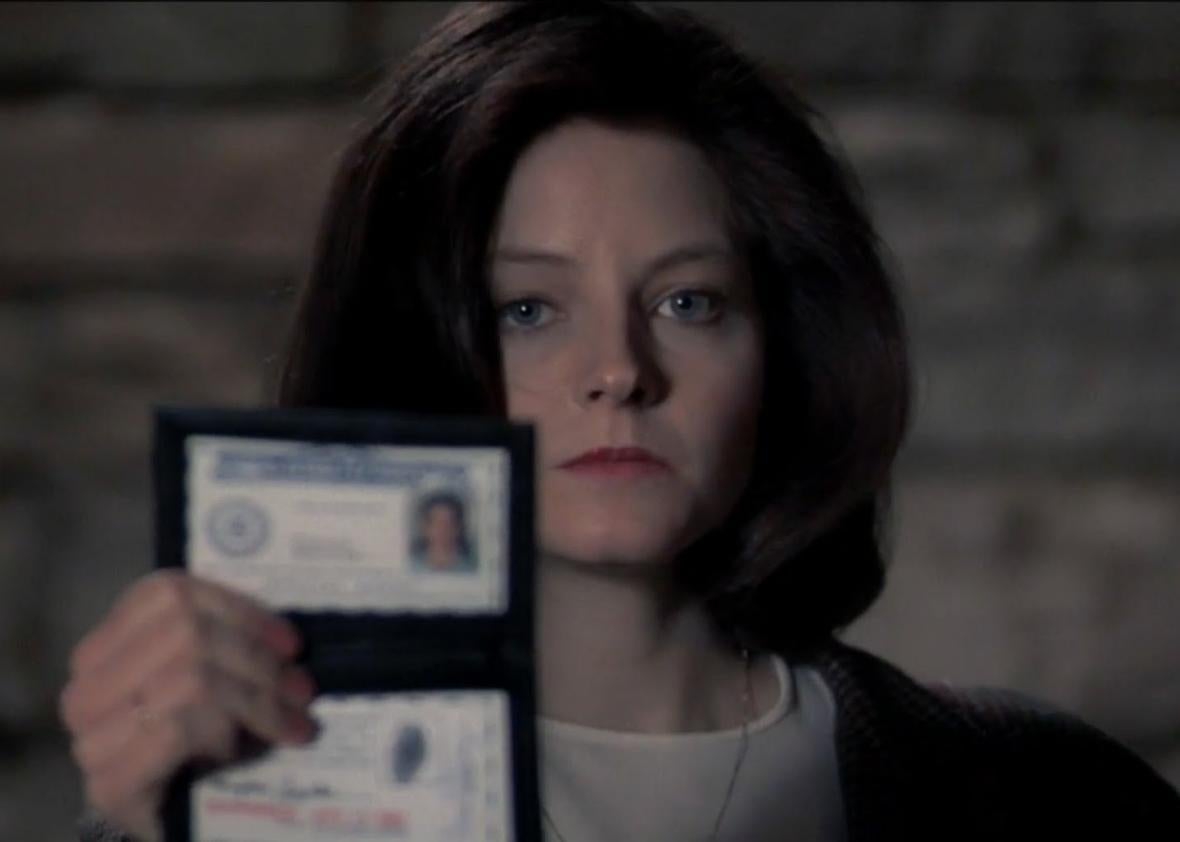

More than a quarter-century after Silence of the Lambs first opened in February 1991, history has delivered a curious wrinkle to the saga. Queer film theorists and activists have never exonerated Demme, and they likely never will, but at least in my mind, the fortunes of his movies have shifted. Fairly or unfairly, Philadelphia is not considered a gay classic; I confess, even as a closeted teenager, to feeling aligned with the movie’s critics, who saw it as a sanitized, claustrophobic, and squeamish pageant of despair. (I still have a hard time watching the funereal dance between Tom Hanks and Antonio Banderas.) In contrast, gay fans have become an essential part of crowning Silence of the Lambs as an enduring classic, not least of all thanks to that bitchy little poodle. There’s the meta sheen of Jodie Foster’s twangy, pant-suited FBI rookie; Anthony Hopkins’ high-class snarls about fava beans, cheap perfume, and a senator’s suit; the killer clown act (“Would you f–k me? I’d f–k me”) that today reads more like a grotesque camp curiosity. I’d wager today’s audiences would more readily register a queer aesthetic in Silence of the Lambs than Philadelphia.

That would undoubtedly amuse Demme, who became a student of the furor over his own movies. His experience in the culture wars, and his evolving and nuanced reaction to it, offer a little-appreciated playbook in how time, patience, and perspective can redefine a director’s legacy.