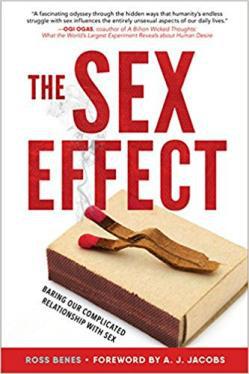

Adapted from The Sex Effect: Baring Our Complicated Relationship With Sex, out now from Sourcebooks.

Back in March, Pope Francis sparked a wave of headlines when he hinted at the possibility of ordaining married men as priests. Since there’s no evidence that church practice will actually change, reactions to Francis’ comments were premature. But the speculators ignored one interesting point: Opening the priesthood to married men would probably reduce the high percentage of priests who are gay.

While doing research for my book The Sex Effect, I came across many scholars who suggested that preventing priests from marrying altered the makeup of the priesthood over time, unintentionally providing a shelter for some devout gay men to hide their sexual orientation. By continuing to disqualify women and married men, the priesthood attracts men who desire to forgo sex for the rest of their lives in an attempt to get closer to God. Because the church denounces all gay sex, some devout gay men pursue the celibate priesthood as a self-incentive to avoid sex with men, which can help them circumvent perceived damnation.

Of course, many factors influence a person’s decision to join the clergy; it’s not like sexuality alone determines vocations. But it’s dishonest to dismiss sexuality’s influence given that we know there is a disproportionate number of gay priests, despite the church’s hostility toward LGBTQ identity. As a gay priest told Frontline in a February 2014 episode, “I cannot understand this schizophrenic attitude of the hierarchy against gays when a lot of priests are gay.”

Sourcebooks

So how many gay priests actually exist? While there’s a glut of homoerotic writings from priests going back to the Middle Ages, obtaining an accurate count is tough. But most surveys (which, due to the sensitivity of the subject, admiittedly suffer from limited samples and other design issues) find between 15 percent and 50 percent of U.S. priests are gay, which is much greater than the 3.8 percent of people who identify as LGBTQ in the general population.

In the last half century there’s also been an increased “gaying of the priesthood” in the West. Throughout the 1970s, several hundred men left the priesthood each year, many of them for marriage. As straight priests left the church for domestic bliss, the proportion of remaining priests who were gay grew. In a survey of several thousand priests in the U.S., the Los Angeles Times found that 28 percent of priests between the ages of 46 and 55 reported that they were gay. This statistic was higher than the percentages found in other age brackets and reflected the outflow of straight priests throughout the 1970s and ’80s.

The high number of gay priests also became evident in the 1980s, when the priesthood was hit hard by the AIDS crisis that was afflicting the gay community. The Kansas City Star estimated that at least 300 U.S. priests suffered AIDS-related deaths between the mid-1980s and 1999. The Star concluded that priests were about twice as likely as other adult men to die from AIDS.

Given that the church has called a gay orientation an “objective disorder” and gay sex “an intrinsic moral evil,” it may seem bewildering why a gay man would chose this profession. But it makes more sense after realizing the church encourages sublimation of homosexuality through prayer. “Homosexual persons are called to chastity,” states the Catechism of the Catholic Church. “By the virtues of self-mastery that teach them inner freedom, at times by the support of disinterested friendship, by prayer and sacramental grace, they can and should gradually and resolutely approach Christian perfection.”

Sexual sublimation is by far the most common theory in the literature as to why there are so many gay priests. There has also been speculation that as a discriminated-against minority group, gay men may be more sensitive to empathize with people—a strong desire to help others leads some of these men to the altruistic priesthood. Another common theme is that clerical celibacy is good cover for gay people wanting to hide their orientation.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ National Review Board reported that “certain homosexual men appear to have been attracted to the priesthood because they mistakenly viewed the requirement of celibacy as a means of avoiding struggles with their sexual identities.” As gay former-priest Christopher Schiavone put it, “I thought I would never need to tell another person my secret, because celibacy would make it irrelevant.”

It’s not as if the church is unaware of this issue. A past president of the USCCB complained about an “ongoing struggle to make sure that the Catholic priesthood is not dominated by homosexual men.” And Pope Benedict once said that homosexuality in the priesthood was “one of the miseries of the church” and that the church needed to “head off a situation where the celibacy of priests would practically end up being identified with the tendency to homosexuality.”

Allowing more married men in the priesthood would probably bring more straight men into the fold, which would reduce the percentage of priests who are gay. Given that the worldwide number of permanent deacons (who can be married and can perform nearly every task required of a priest except consecrate the Eucharist or hear confessions) has increased by nearly 40,000 people in the past forty years, there appears to be a large group of married men open to clerical life.*

But just because some church officials would like to see fewer gay priests doesn’t mean that a change in discipline would benefit the institution. A large percentage of priests being gay doesn’t automatically equate to a crisis or indicate that church teaching should change. Though other denominations have shown that women, married men, and sexually-active LGBTQ people can be entirely competent as pastors, for centuries the Catholic Church’s model of relying on single, sexually-abstinent men has generally served the institution well. And most Catholic priests are psychologically well-adjusted and satisfied with their lives and occupation.

Rather, the gaying of the priesthood denotes a complex phenomenon that makes many people uncomfortable, an example of sexual regulations producing unintended consequences. For the most part, the church continues to downplay shifting cultural contexts in favor of adhering to sexual renunciation laws developed by ancient eschatological communities and desert ascetics responding to an uncertain world. The church also continues to rely on clerical structures that were influenced by social and economic conditions from the Middle Ages.

In doing so, the hierarchy has contributed to a phenomenon it would rather have people ignore: Rigid policies on homosexuality and clerical celibacy have inadvertently driven many gay men toward the priesthood. “Bishops are caught in the middle and running scared,” priest-theologian Richard McBrien told reporter Jason Berry in his book Lead Us Not Into Temptation. “They live in a church with a very hardline policy on homosexuals, yet they realize they’re drawing from that population well beyond its presence in society, by default.”

A paradox of this magnitude seems baffling. And it certainly is baffling for the gay priests who battle cognitive dissonance. But as an entry in Human Sexuality in the Catholic Tradition points out, “Christian faith proclaims its deepest truth in paradoxes.” The contemporary church’s greatest paradox may be that its positions of authority continue to be heavily represented by people it declares “objectively disordered.”

*Correction, April 20, 2017: This post originally mischaracterized the Church’s policy around permanent deacons and marriage. A married man can become a deacon, but he may not marry after becoming one without special permission.