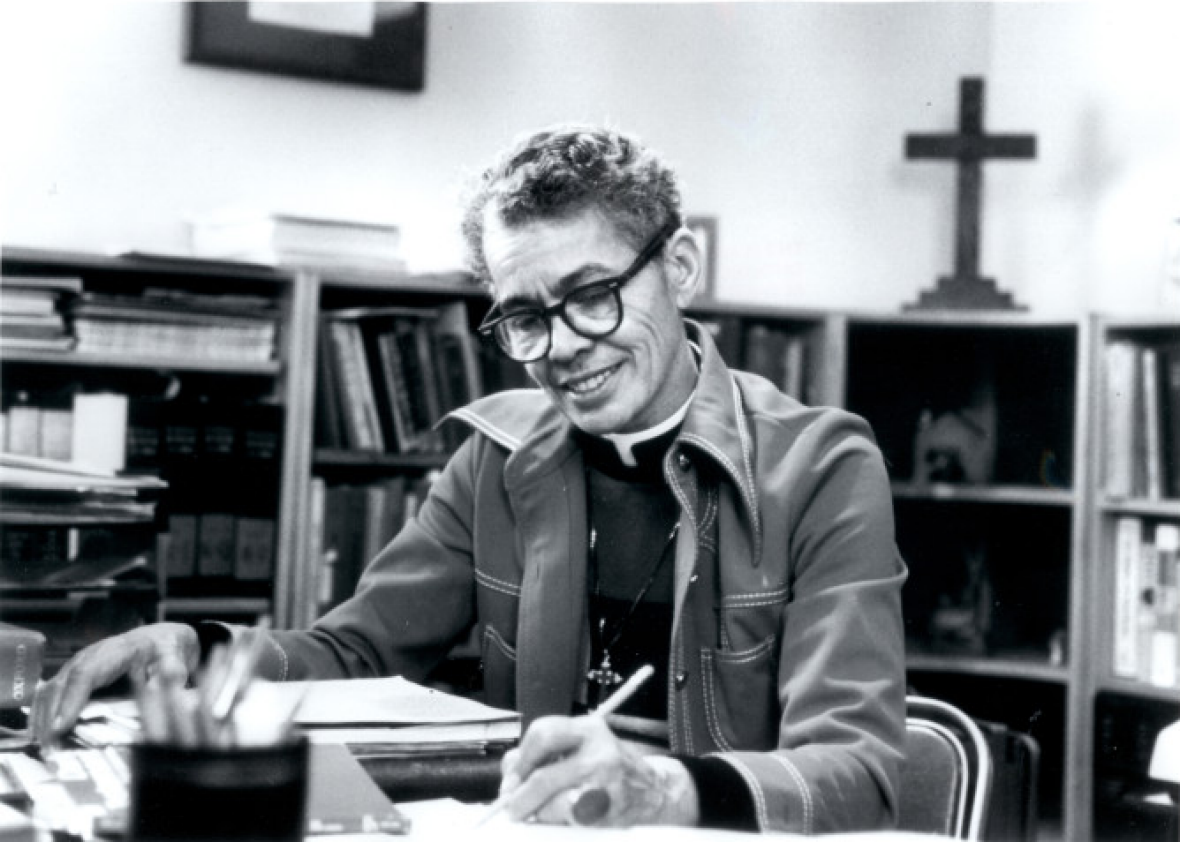

Being “in between” was both a curse and blessing for Pauli Murray, born Anna Pauline Murray, in 1910. Growing up in a segregated North Carolina, Murray displayed at an early age an artistic mind and a preference for the boys’ section of the clothing store. Variously tormented and buoyed in her life by her status as a woman, being of mixed race, and as a self-professed “boy-girl” who believed in her bones that she was really a man, Murray endured to become a journalist, an activist, a professor, a priest, and a lawyer who made monumental contributions to civil rights and women’s rights.

So why do we know so little about Murray, who, for example, laid out the seminal legal argument that Ruth Bader Ginsburg pursued to extend the Equal Protection Clause beyond the protection of white men? In 1971, Ginsburg, building on an influential law article Murray co-wrote, successfully persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court that the Fourteenth Amendment should apply to protecting both women and other minority groups from discrimination.

Barnard historian Rosalind Rosenberg, author of an exhaustive and transfixing new biography, Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, sheds light on the dearth of information. The main reason: The executor of Murray’s estate, who holds the rights to 135 boxes of Murray’s most intimate reflections in the form of diaries, correspondence, legal briefs, and other archival material, was highly protective of how Murray would be portrayed following her death in 1985. “I think that’s why it’s taken so long for anyone to try to delve a little bit more deeply into her life,” Rosenberg told me.

Oxford Press

Rosenberg explained that publication of her book had actually been delayed because the family was horrified that Murray would be portrayed as anything other than completely middle-class and respectable. In particular, they disputed Murray’s gender identity. “This can’t be true; I would have known; I was very close to my great aunt,” Rosenberg said some relatives told her. Yet, in sifting through the boxes of archival material, Rosenberg had uncovered an astonishingly complex individual who was as petrified of being found out for her nontraditional gender identity as she was outspoken about human rights.

Murray believed identity and sexual orientation were private matters, and she discussed them with only a few intimate friends. So while she was elated on the occasions she was taken for a man, she does not appear to have asked to be identified as such. Rosenberg initially experimented with the use of pronouns in writing the book, concluding those efforts ultimately struck her as ahistorical. “Murray lived in a gender-binary culture,” she said.

It is within this context that Jane Crow, in its sensitive and nuanced synthesis of Murray’s private journal notes, determines she likely thought of herself as what we would now understand as transgender. Specifically, Murray viewed herself as a man in a woman’s body who fell in love with heterosexual, mostly white, women. For most of her life, science did not have the language to identify her dysphoria. To ameliorate it, Murray sought for many years a medical professional who would administer testosterone hormone therapy. None would agree to it.

Despite that inner turmoil, Rosenberg theorizes that Murray’s identification as a man may have propelled her to greater heights, giving her the confidence to aspire to go to law school in 1941, when so few women did: “She did not internalize the whole range of self-defeating attitudes our culture inculcates in those who identify as women.” Murray’s existence outside of so many societal boundaries also informed her understanding of injustices under the law. “It made her relentless,” said Rosenberg, “in-betweenness in terms of her gender, her race and her class, and her growing conviction as she aged that she had the power to turn what was a torment into a strength.”

Murray was acutely aware of what it meant to be both black and a woman—both Jim Crow and what she coined as “Jane Crow”—prejudice based on gender. She observed that not only have black women “stood shoulder to shoulder with Negro men in every phase of the battle, but they have also continued to stand when their men are destroyed by it.”

The first black person—male or female—to earn a J.S.D. from Yale Law School, Murray made it her legal quest and a life mission to eradicate Jane Crow. When Eleanor Roosevelt appointed her in 1962 to the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, Murray furthered her argument that discrimination on the basis of gender paralleled discrimination on the basis of race. That commission role was one of many prominent and leadership positions Murray held throughout her life, even while she often struggled financially.

Indeed, Jane Crow inspires at once a wonder at how much the brilliant Murray accomplished, as well as a deep sadness in how the world failed in many cases to acknowledge and celebrate her achievements. Societal injustice and its stringent mores both impeded and obscured her success.

“This conflict rises up to knock me down at every apex I reach in my career,” Murray confided in an open-hearted letter to her beloved Aunt Pauline. Written while she was in law school, it mentions her attraction to an undergraduate woman on campus and the potentially harmful gossip that ensued when people learned of it. Aware societal laws failed to protect her in the situation, Murray lamented: “I’m exposed to any enemy or person who may or may not want to hurt me.” As her legacy makes plain, Murray toiled for much of her life to eliminate the root causes of exactly that fear.