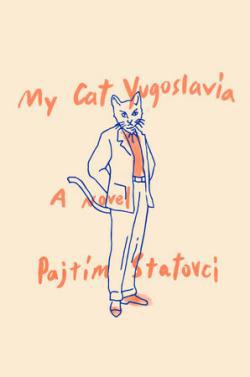

A man walks into a gay bar and there he meets a talking cat. “I noticed the cat across the dance floor,” Bekim, the lonesome, dislocated narrator of Pajtim Statovci’s compelling and altogether beautiful debut novel My Cat Yugoslavia, tells us. “I had never seen anything so enchanting, so alluring. He was a perfect cat” with gleaming fur and muscular back legs. “Then the cat noticed me; he started smiling at me and I started smiling at him, then he raised his front paw to the top button of his shirt, unbuttoned it, and began walking towards me.”

Bekim is the youngest son of a broken family who, with his parents, came as a refugee from Kosovo to Finland in the early 1990s. He was a disturbed child who grappled with darkness and nightmares. His father, Bajram, was violent and once hired a Turkish imam to exorcise evil spirits from Bekim’s body. My Cat Yugoslavia opens with Bekim as a twentysomething college student cruising for a hookup online.

Meeting this sexy, snarky, spunky talking cat changes Bekim’s life. In spite of his cruelty—“Gays. I don’t much like gays,” the cat reveals at the bar, causing Bekim to wonder why he’s there in the first place—Bekim begins to tell him everything about his life, where he had come from, and what it’s like to feel as if you’re always being scrutinized. It is fair to say Bekim falls head over heels for this cat, and this encounter—which leads to the demanding, tempestuous creature moving in and then out of his apartment—sets in motion Bekim’s return to Kosovo and an inevitable facing of his past.

Statovci, only 26 years old and himself born into a Kosovar Albanian family that migrated to Finland when he was only 2, has said that his choice to insert a talking cat into My Cat Yugoslavia was done “to explore stereotypes we have about ethnic, sexual, and religious minorities.” By this, he not only meant that animals tend to have certain characteristics or qualities ascribed to them, but also that societies create a kind of hierarchy of animals in the same way as people continue to be distinguished and oppressed on the basis of weakness or undesirability.

This image of a talking cat within human society is also a way of examining the displacement and denigration that comes with being a Muslim Kosovar refugee in Western society, and a queer person in a culture with certain sexual and gender norms. “Maybe it was because I left the war and the destruction that followed it somehow stole my personal history and inserted another history in its place,” that I wrote the novel in this magical realist way, Statovci has said. War and displacement “silenced my voice and made me smaller, took away my right to not be a part of the world that was being presented to me, ‘the world in ruins,’ the right to define myself outside the imagery that other people had when they heard about where I came from.”

Perhaps because this is a literary debut, Statovci’s magical realism and use of symbolism can sometimes come across as heavy-handed. The novel’s construction—with Bekim’s narrative interwoven with that of his mother, Emine—is not as sophisticated as it could be. Still, My Cat Yugoslavia is inventive and playful. It tells us a great deal about what it might feel like to be an outcast twice-over, to be at the bottom of the heap not just in one society but two, to experience, as Bekim says, a loneliness “so brutal that sometimes it felt as though nobody knew I even existed.”

My Cat Yugoslavia’s is also elevated by the quality of the writing (aided, to be sure, by David Hackston’s elegant translation from the original Finnish). There is something truly wonderful about a debut novel where the sentences themselves are as beguiling, the metaphors as imaginative (“its dry skin rattled like a broken amplifier”; “his viscid sweat oozing between my fingers like egg white”), and the eye for detail as sharp as Statovci’s.

As a portrait of a gay refugee, Statovci writes as well about unemotional hookups—“He gripped my wrist in his palms and pressed his thigh against my groin, as though he was afraid I might say something like I fancied him or … how I understand him”—as finding love:

I didn’t answer. He glanced quickly out of the window where the evening was beginning to darken and turn red. What if I stopped loving him or what if he could no longer bring himself to say it, or what if he fell in love with someone else or got a job on the other side of the world? Anything could happen. He could die.

…“Don’t think too much. That’s your problem.”

He moved his hand on my stomach; his fingertips felt warm and soft and his skin smelled of sliced almonds.

Then I said it too, because it would have been sheer madness not to say those words to a man like that.

At a time when there is a shortage of empathy for refugees both here and in Europe, Statovci’s queer perspective on the search of rootedness in My Cat Yugoslavia is wonderful and original—and much welcome, too.