The 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals’ landmark 8–3 ruling in Hively v. Ivy Tech was an extraordinary victory for LGBTQ advocates, overruling bad precedents and replacing them with an expansive interpretation of nondiscrimination law. Most coverage of the decision has, understandably, focused on its core holding: that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s ban on “sex discrimination” encompasses sexual orientation, outlawing employment discrimination against gay, lesbian, and bisexual workers. But the decision is noteworthy for another reason: It wipes off the books an odious yet influential anti-trans decision, clearing the way for a follow-up decision holding that Title VII also bars discrimination on the basis of gender identity, including transgender status.

Ulane v. Eastern Airlines, the terrible precedent in question, has long been a bête noire of civil rights attorneys. Decided in 1984, Ulane involved a pilot, Karen Frances Ulane, whose airline fired her for transitioning from male to female. A district court found that Title VII’s prohibition against sex discrimination protected Ulane; after all, her airline had terminated her for transitioning from one sex to another. Surely a decision so rooted in sex-based considerations constitutes discrimination “because of sex.”

But a panel of judges for the 7th Circuit reversed. The court asserted that Title VII “implies that it is unlawful to discriminate against women because they are women and against men because they are men,” and nothing more. It noted that Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination was added late in the legislative process (true) as a poison pill designed to sink the whole bill (untrue). From there, the court reasoned that “the total lack of legislative history supporting the sex amendment coupled with the circumstances of the amendment’s adoption clearly indicates that Congress never considered nor intended that this 1964 legislation apply to anything other than the traditional concept of sex.” So Title VII cannot be read to protect “homosexuals, transvestites, or transsexuals.”

This feeble logic never really made sense. As Justice Antonin Scalia once wrote in the context of Title VII, courts should look to the words of a statute, not its history, to determine its meaning. “Statutory prohibitions often go beyond the principal evil,” Scalia explained, “to cover reasonably comparable evils, and it is ultimately the provisions of our laws rather than the principal concerns of our legislators by which we are governed.” But the Ulane court applied a very different theory: If a court can’t divine “the principal concerns of our legislators,” it should construe a statute as narrowly as possible. Thus, trans people cannot possibly find protection under Title VII.

Despite the novelty and incoherence of this principle, Ulane has spread like kudzu throughout the federal judiciary. Every court to find that Title VII does not protect transgender and gender nonconforming employees cites Ulane as persuasive precedent. Every judge who argues for an anti-LGBTQ interpretation of Title VII points to Ulane. Every attorney defending an employer against an anti-trans discrimination lawsuit relies upon Ulane. The decision has blocked progress for decades.

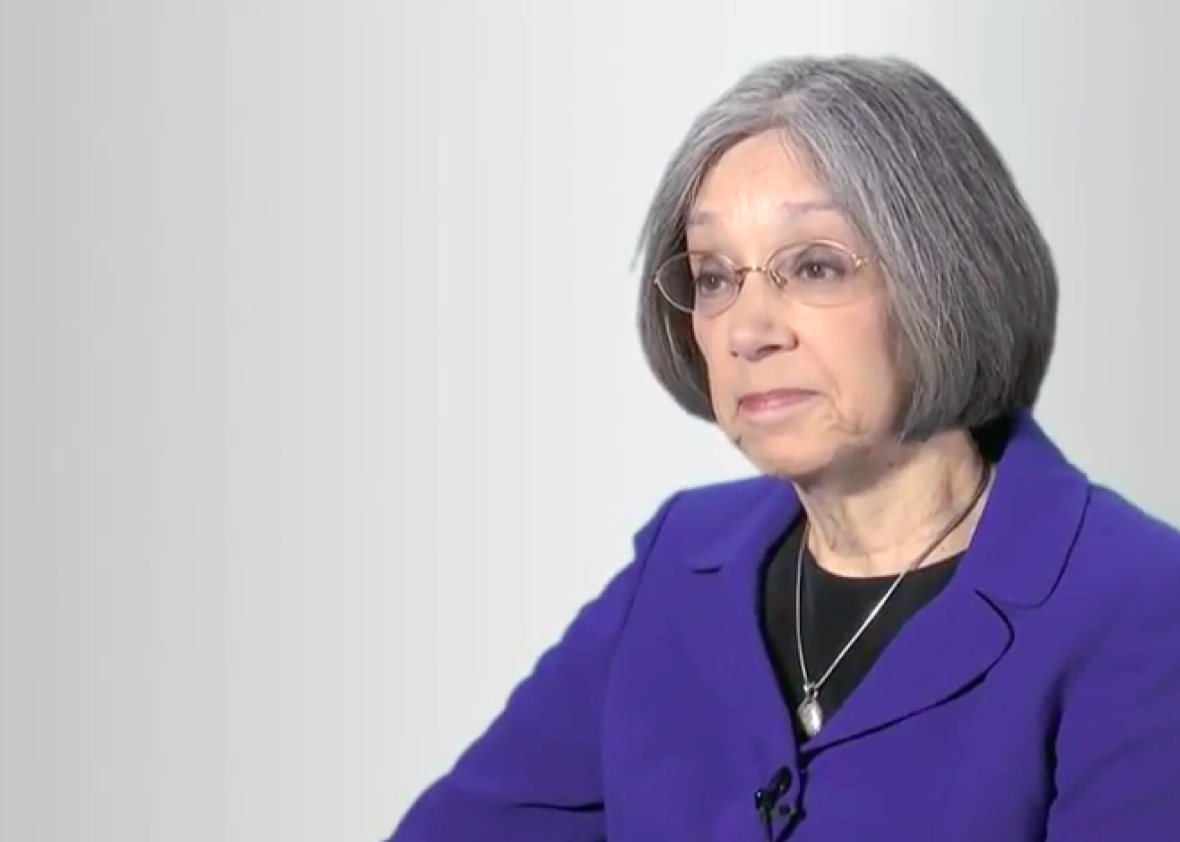

And now it is gone. In her majority opinion, Chief Judge Diane Wood announced that the court had “overrule[d] our previous cases” taking a cramped view of sex discrimination. “[T]he idea that discrimination based on sexual orientation is somehow distinct from sex discrimination,” Wood noted, “originated” with Ulane. (After all, the Ulane court reached out beyond the question before it to determine that Title VII does not encompass gender identity or sexual orientation.) Hively therefore overturned Ulane. And every decision to cite Ulane now rests on overruled precedent.

Even better, Wood’s Hively opinion deploys analysis that applies to gender identity as well as sexual orientation. Sex discrimination, Wood explained encompasses sex stereotyping, or failure to conform to gender norms. Obviously, insisting that an employee identify as the sex they were assigned at birth—or adhere to gender norms related to that sex—involves sex stereotyping. Wood also endorsed the textualist theory of sex discrimination, which crosses over neatly into the transgender context. When an employer discriminates against a worker for switching sexes, he is literally engaging in discrimination “because of sex.” But for the individual’s transition from one sex to another, she would not have fired. That fact gives her grounds to sue under Title VII.

Hively does not quite spell all this out, but the handwriting is on the wall—and with Ulane off the books, the court will likely do so very soon. That decision will finally bring the 7th Circuit’s interpretation in line with the plain text of Title VII. As the Hively court recognized, it is simply impossible to erect a barrier between sex discrimination and anti-LGBTQ discrimination. Anti-gay and anti-trans bigotry can always been traced back to anachronistic ideas about the proper role of the sexes. Title VII was designed to strike these stereotypes from the American workplace. The 7th Circuit is poised to accomplish that goal.