Dozens of groups filed amicus briefs this week in Gloucester County School Board v. G.G., a key transgender rights case at the Supreme Court. The case involves Gavin Grimm, a transgender high school student who sued his school board after it prohibited him from using the boys’ bathroom. Grimm asserts that Title IX’s prohibition on “sex discrimination” in education guarantees him access to the facilities that align with his gender identity. Many of the amicus briefs filed on his behalf cogently explain why Title IX must be read to forbid sex stereotyping and discrimination on the basis of transgender status.

But one brief, filed by the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, together with the Columbia Law School Sexuality and Gender Law Clinic and the law firm Stris & Maher, tackles a somewhat different topic: The vile history of bathroom segregation in the United States. As the brief explains in its opening passage, “there is a lengthy and troubling history of state actors using public restrooms and similar shared spaces to sow division and instill subordination.”

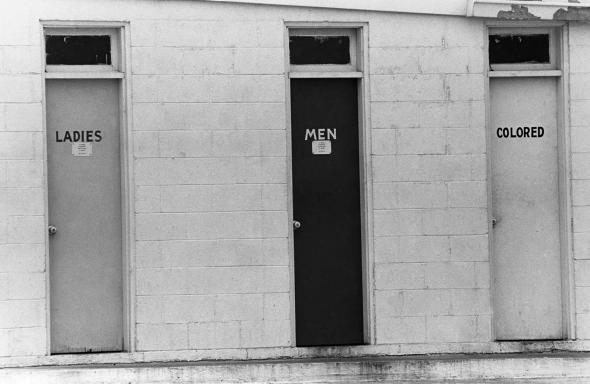

Not so long ago, bathrooms nationwide were designated “Colored Only” and “Whites Only.” A key lesson of that painful and ignoble era is that while private-space barriers like racially segregated bathrooms may have seemed to some like minor inconveniences or insignificant sources of embarrassment, they were in fact a source of profound indignity that inflicted deep and indelible harms on individuals of both races, and society at large. This disreputable tradition of state and local governments enshrining fear or hostility toward a disfavored group of people into laws requiring their physical separation from others should encourage this Court to view with skepticism the rationales proffered by local officials here.

Moreover, the brief notes, “state officials often justified physical separation in restroom facilities, swimming pools, and marriage by invoking unfounded fears about sexual contact and exploitation.” Needless to say, “purported concerns about sexual predation currently used as a basis for excluding transgender students from school bathrooms uncomfortably echo those used to justify the separate bathrooms for racial minorities.” And “the arguments offered to defend the discriminatory singling out of G.G. are painfully similar to those that this Court long ago deemed to be insufficient to justify discrimination based on race.” As the brief spells out:

The proposition that G.G. should go back to using the “separate restroom” parrots the functionalist logic that this Court discarded along with “separate but equal.” The Trump Administration’s recent withdrawal of the guidance on transgender students and its description of bathroom access as a “states’ rights issue” only amplifies the disconcerting historical echoes in this case. State and local officials often invoked “states’ rights” as a basis for opposing this Court’s decisions and insulating prohibited discrimination from statutory and constitutional review. Indeed “states’ rights” was the frequent refrain of officials who fought against racial integration, including in bathrooms. Ultimately, however, the claim of “states’ rights” has no relevance to this Court’s interpretation of a federal statute—in this case Title IX—as states are bound by this Court’s interpretation of federal law.

“We must not repeat the mistakes of the past,” the brief declares. “These all-too-familiar arguments—about sexual contact, predation, danger, and discomfort—remain both factually baseless and legally immaterial. Instead, the weight of precedent and the guarantee of equal protection inexorably support this Court in recognizing G.G.’s simple and inherent dignity by letting him use the boys’ bathroom with his peers.”

The brief goes on to detail “the physical separation of bathrooms by race, a defining feature of the Jim Crow era.” These state “visited an immeasurable indignity on African Americans”; many black parents “instructed their children to use the facilities at home and avoid using segregated public facilities. Often the use of segregated bathrooms involved walking long distances, in front of others, which further underscored the separateness and shame involved.” Bathroom segregation was justified by fear of “the high venereal disease rate among Negroes” and the alleged threat of sexual violence by blacks. Similarly, segregationists vigorously opposed the integration of swimming pools, claiming that “black men would act upon their supposedly untamed sexual desire for white women by touching them in the water and assaulting them with romantic advances.”

These bigoted antipathies have obvious parallels to the fight against transgender bathroom use. Gloucester County, along with the many amicus briefs supporting its attack on Grimm, insist that trans bathroom access creates a safety issue, allowing debauched students to assault unsuspecting victims in their most vulnerable moments. At the school board meeting at which the anti-trans policy was instituted, speakers called Grimm a “freak” and compared him to a person who thinks he is a “dog” and wants to urinate on fire hydrants. One speaker encouraged the creation of a bathroom just for Grimm, urging the school to divide the students into “a thousand students versus one freak.”

Gloucester County’s anti-trans policy is about health and safety as much as race-based bathroom segregation was—which is to say, not at all. “This Court,” the brief concludes, “must treat the arguments” against trans bathroom use with skepticism similar to that with which it treated arguments against racially integrated bathrooms. In both instances, bathroom segregation is motivated not be genuine safety concerns, but rather animus cloaked in flimsy pretense. And the Supreme Court must recognize that anti-trans discrimination does not become lawful simply because it is swathed in pretextual anxieties rooted in prejudice.