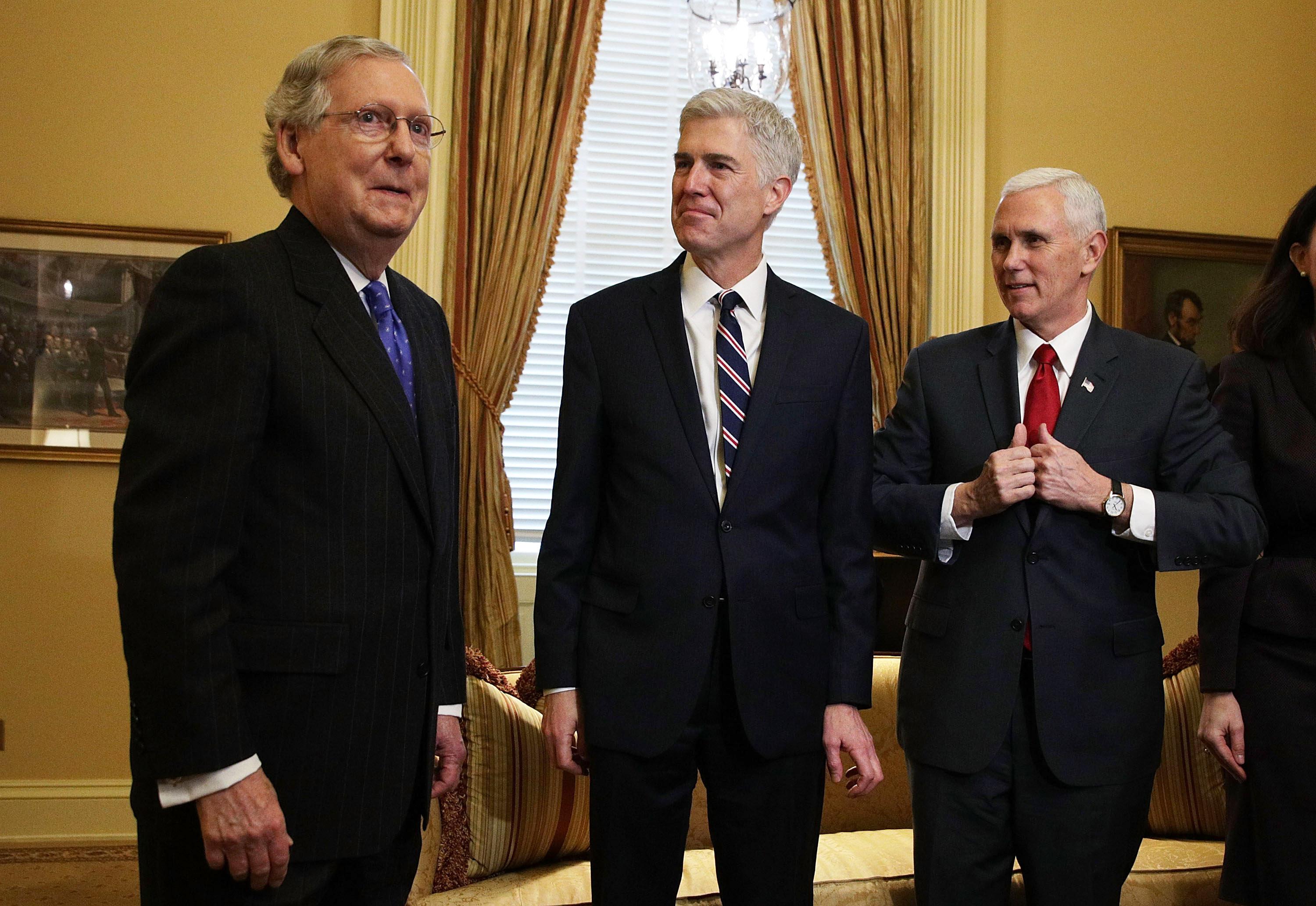

Even as an undergraduate student at Columbia University in the late 1980s, Neil Gorsuch—who on Monday became President Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court—was already showing signs of a vision shaped and narrowed by conservative ideology. As a classmate of his, I saw it firsthand—and, if those early days are any indication, supporters of LGBTQ equality should be wary.

In 1985 and ’86, as president of the Columbia Gay and Lesbian Alliance—the world’s oldest LGBTQ student group—I was involved in some of the hotter political topics on campus that year, some of which became issues in student government campaigns. In the lead-up to student senate elections—in which Gorsuch ran—the Columbia Spectator, CU’s campus newspaper, posed a series of questions to the candidates in March 1986.

Most revealing is Gorsuch’s answer to the first: “Do you think the marines should be allowed to recruit on campus?”

Before his answer, a bit of background: In 1985, after over a decade of interviewing off campus in the neighborhood, the CU School of International and Public Affairs had quietly allowed the U.S. Marines back onto campus for recruiting interviews. Since the Vietnam war protests of the late ’60s, Columbia had barred recruiting and military training programs like the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) from campus partially due to the military’s discriminatory policies against certain minorities—a tradition that the SIPA move violated. I lead the effort (petitions, protests, leafleting, articles, CU Senate actions) to call on the University to enforce its own CU Senate resolutions banning discrimination against gay and lesbian people in all CU programs and facilities, which had been observed for over a decade, and once again bar discriminatory military recruitment from campus. This was the context behind Spectator’s question.

While the majority of candidates disapproved of the Marines’ return, Gorsuch had a different—and disconcertingly chilly—view:

The question here is not whether “the Marines should be allowed to recruit on campus” but whether a University and its community, so devoted to the freedom of individuals to pursue their own chosen lifestyles and to speak freely, has the right or obligation to determine who may speak on campus or what may be said. To fulfill an immediate end, we are likely to forget the underlying principle that every human being, according to our nation’s proclamations and reinforced by our University’s standards, has an inalienable right to express himself or herself—whether we agree or not. Free speech works; it works better than any form of censorship or suppression; and in exercising vigorously, the truth is bound to emerge.

This came as no surprise. At the time, Gorsuch was already writing and establishing a reputation as a conservative ideologue. He framed the issue as purely a matter of free speech: that discriminatory recruitment was an act of speech alone; that the university’s primary obligation was to free speech; and that the only cure for bad speech was more speech. His perspective completely ignored the realities that in these recruiting interviews, decisions were made and lives changed: Opportunities and scholarships were granted; careers launched; future paths toward prosperity, inclusion, and power were directed, granted, and denied as a product of the speech which was necessarily part—but only a part—of the activities involved. The simple fact of the matter was that by using Columbia resources, the U.S. Marines were facilitated in offering various resources and opportunities to some students, but denying them to others solely on the basis of their sexual orientation.

Gorsuch’s abstract answer—disconnected as it is from the lived realities of sexual minorities at the time—seems as blinkered to me now as it did then. One would need to willfully narrow his vision to see recruiting as an act of speech alone. The opportunity conferred by those interviews was considerable—and at an institution committed to equality, that kind of opportunity must be available to all. In 1986, Gorsuch was able to reason his way to a position in which reality was unrecognizable. It was not a perspective I, nor most at Columbia, gave much credence at the time. And thankfully, it’s not one that’s held up in the courts. But now that Gorsuch is poised to join the Supreme Court, it’s one that should be cause for concern.