Recently, I saw Catherine Opie’s self-portrait Dyke (1993), a photograph currently on display at the Whitney Museum in New York. Opie is a contemporary photographer credited for bringing images of BDSM into mainstream culture in the 1990s. In comparison to her other work, Dyke is relatively tame and often overlooked. Like many lesbians, I was familiar with Opie’s work prior to entering the exhibit. Still, standing in front of Dyke, I was struck by Opie’s engagement with a problem that all lesbian artists must face: Images of us made by straight people are so often sexualized—so how can we show our bodies without playing into that narrow and damaging paradigm?

Admittedly, Opie’s Dyke is not the most inviting portrait. Opie’s body does more than exist in this image; it dominates it. Opie faces away from the camera, offering audiences a view of her freckled back, her buzzed hair, the jagged points of her elbows. Initially, we see a body that—like most bodies without a view of the genitals—reads as androgynous. This is a body that could be anyone or anything; but as the Old English inspired tattoo on the back of her neck indicates, this is the body of a dyke. The word dyke signals that this body lives in a particular sexuality, but Opie’s composition tempers that fact with a statement of resistance: The body of this dyke is not available for your consumption.

Opie’s posture of defiance doesn’t arise in a vacuum. In general, lesbians struggle to achieve nuanced representation in the media. There are the stereotypical lesbians that exist only as the punchline of jokes, of course—unattractive by heteronormative standards in their cargo shorts and buzzcuts. On the other—and more common—end of the spectrum, we see the hypersexualized and performative lesbians frequently found in pornography.

Not that mainstream representations are immune from the porn impulse. In The Handmaiden (2016), for example, viewers see lesbian sex through the eyes of male director Park Chan-wook. Unflinchingly explicit, the film invites audiences to see the women’s bodies without obstruction. The stylized sex, heavy on artistic imposition, feels closer to performance art than real lovemaking. And Abdellatif Kechiche’s 2013 film Blue Is the Warmest Color also falls into the trap of hypersexualization. In an otherwise aching film about one young woman’s journey from adolescence into adulthood, Keniche directed the couple in a seven-minute-long sex scene geared more toward titillation and voyeurism than an honest depiction of a teenager’s first same-sex experience.

IMDB

The sexualization of lesbians is so prevalent and well-documented that there is literally enough material for a book on the subject. This book, titled Lesbians for Men, features more than 300 photos of mostly straight women engaging in same-sex acts meant to tantalize male viewers. It’s a potent reminder of the difficult space in which lesbian artists must create their work.

But what’s the solution? Opie offers a clue: Lesbian artists must resist the audience’s expectations. They turn away from the viewer, fragment and shield the body, acknowledge and reject the sexualization the audience has come to expect.

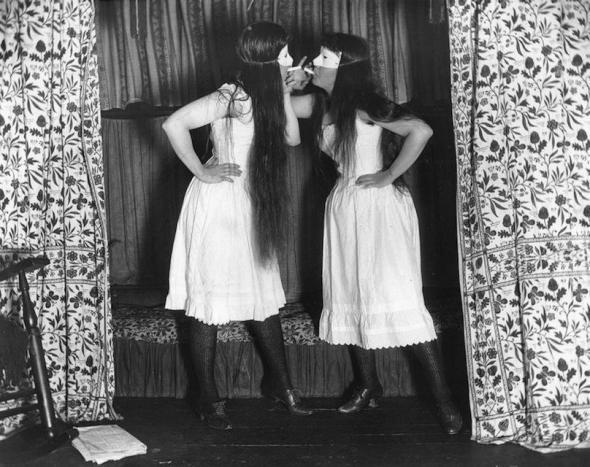

In lesbian art, this kind of fragmentation has a long history, dating back to the first female photographer, Alice Austen. Austen, a lesbian photographer from Staten Island who was born in 1866, has become known for documenting queer people in their daily lives. One of Austen’s most well-known works is a self-portrait of her and her life-partner, Gertrude, called Trude and I Masked. Taken in 1891, the two of them don masks and pose in corsets—a startlingly risqué choice for the time period. Masks, of course, play with the concept of the double-life split between heteronormativity and queerness that was enforced at the time. Their bodies turn away from the camera. The photo is clear: You know we’re lovers, but you don’t know who we are.

Austen is relatively unknown today, but there are high-profile lesbian photographers working in the mainstream who echo her work, a progeny of which Annie Leibovitz is probably the most prolific. Her famous shot of bikini-clad Ellen DeGeneres pointedly fragments the lesbian body. In the shot, Ellen holds her breasts for no clear reason; she is, after all, wearing a bikini top that conceals her breasts and nipples. A cigarette in her mouth, shoulders back, chest out, and briefs peeking from beneath her shorts—in this shot, Ellen is unapologetically queer. Much like Opie, Ellen’s body dominates the frame and oozes masculinity, turning traditional gender norms on their head. With her hands over her breasts, a second layer of protection, she also unapologetically obscures her body, disinviting the typical sexualized reception.

Damiani / Amazon

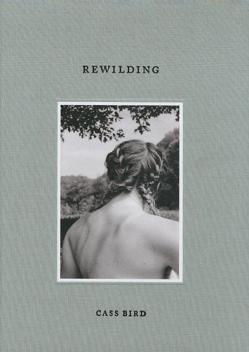

Cass Bird is another lesbian photographer who documents the queer body. Her 2012 book, Rewilding, captures a group of young queer women as they explore their sexualities and gender expressions. The cover of Rewilding obscures the queer body quite literally: a woman’s shoulders take up most of the shot, her face turned entirely from the camera. Her messy braids suggest youth and innocence, and her lack of a shirt suggests promiscuity and freedom. In the context of the project, we can assume she is queer, and we can assume something else: Though it documents queer women’s bodies and experimentations, this book is decidedly not lesbian sex for men.

South African lesbian photographer Zanele Muholi takes this strategy of fragmentation and applies it in an even more overtly political fashion. Across the board, queer people in South Africa face high levels of discrimination and violence, and for lesbians, corrective rape—rape performed under the rationalization that it will turn a woman straight—is a relative epidemic. Muholi’s portrait series, Faces and Phases, celebrates black lesbians in South Africa, many of whom are survivors of corrective rape. These images are black and white, initially unassuming, with the subject’s faces unobscured, eyes on the camera. The women appear in fragment, often from the waist up, with a limb out of focus, or a close-up of legs with a long scar on the thigh. Muholi’s fragmented images assert that surviving violence is one aspect of identity, but not everything.

At the Whitney, I was moved by the strength in Dyke, the power in resistance. I was also surprised at the vulnerability Opie allowed, an aspect of the portrait I hadn’t before noticed. If I stayed in front of Dyke long enough, I realized, I could count the photographer’s freckles. In art, women both queer and straight are often reduced to the whole body: Is she sexy, or not? If two women are in the image, are they sexy, or not? Lesbian artists, at their best, strive to celebrate the female body, where straight society crassly desires, prejudicially rejects, or simply overlooks it. In turning away from the viewer, lesbian artists not only reclaim lesbian identity from the vandalism of hypersexualization, but also insist on the beautiful reality of the female body beyond sex: a single scar, a mess of braids, a slew of freckles on a turned back.