“Rarely is a documentary as well attuned to its subject as Howard Brookner’s Burroughs,” the New York Times raved in October 1983. Brookner’s filmmaking debut was a study of writer William S. Burroughs, made when the young director was fresh out of NYU. Janet Maslin wrote, “The quality of discovery about Burroughs is very much the director’s doing, and Mr. Brookner demonstrates an unusual degree of liveliness and curiosity in exploring his subject.”

Six years later, mere months before the release of his third movie and first feature film, Bloodhounds of Broadway, Brookner died of AIDS at his home in New York at the age of 34.

The notion of a shortened life lived to its fullest informs the sensibility of Uncle Howard, a fine new documentary about Brookner’s life, which opens at New York’s IFC Center on Nov. 18. Directed by Brookner’s nephew, Aaron Brookner, Uncle Howard only occasionally takes flight, but it is a noble effort nonetheless. It is an act of discovery or restoration as much as anything else, and it begins with the unearthing of a long-lost archive in a lower Manhattan apartment.

Howard Brookner inspired Aaron to make movies, but when his life ended, he became something of a myth until it was revealed that he had left behind an archive. Burroughs took five years to make, and all the notes and negatives associated with its production had been locked away in Burroughs’ old apartment, known as The Bunker, at 222 Bowery. All these materials had fallen into the possession of the poet John Giorno, who lived in the same building as Burroughs. After much persuasion, he allowed Aaron to take them away.

This archival footage forms the visual basis for the first third of Uncle Howard. At first, Brookner was nervous around the legendary Burroughs, who had a reputation as a suspicious, even paranoid, person with a firm belief in the presence and power of extraterrestrials, among other things—and worried about how he would actually pull this movie together as a first-time director. In the end, he came as close as anyone to portraying Burroughs’ psychology on screen, because he got his subject to trust him.

After Burroughs came Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, his 1986 documentary about what ended up being experimental playwright Wilson’s futile attempt to stage a multinational opera to coincide with the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, and Bloodhounds of Broadway. Starring Matt Dillon and Madonna, this ensemble comedy—set in the gangster, gambler, and hustler world of Prohibition-era Manhattan—was based on four Damon Runyon stories. (The same author and world inspired the musical Guys and Dolls.)

When compared with the attention devoted to Burroughs, Brookner’s two other movies receive short shrift in Uncle Howard, perhaps because they did not achieve the same sort of critical success or cultural impact. Vincent Canby, writing in the Times, said Bloodhounds of Broadway “never gets going. It ambles pleasantly.” The movie plays “as if it were a series of vaguely connected opening sequences,” a “built-in fault” of Brookner’s screenplay and direction.

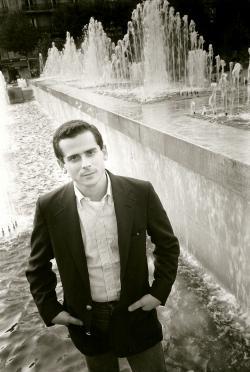

Paula Court, estate of Howard Brookner

Uncle Howard is particularly powerful when dealing with the personal and familial, and how those aspects intersect with the professional. Brookner was fantastically handsome with an inexhaustible charm. He was also gay, something about which his parents were never wholly comfortable, at least initially. Brookner’s partner, Brad—with whom he lived at the Hotel Chelsea—posits that Burroughs became a father figure to Brookner.

Life and work collide in the making of Bloodhounds of Broadway. Brookner had been diagnosed as HIV-positive before filming began, and he was taking AZT—a drug prescribed to delay the development of AIDS—but, believing it tired him and clouded his thinking, he went off the drug. This turned the making of Bloodhounds of Broadway into a race against time. Brookner had requested the right to final cut, asking the producer, Lindsay Law, “What if this is my only film?” words that haunt him still, unable to fathom at the time why Brookner would ask. Brookner completed filming, but deteriorated rapidly thereafter. He gambled with AIDS and lost.

At times the documentary doesn’t quite seem to know what to do with the wealth of material it has uncovered, and the meta aspect of the documentary—making a documentary in part about the making of a documentary—is a narrative trick that is beginning to feel a little worn out. Still, Uncle Howard is a worthy reconstruction, even perhaps a resurrection, of Howard Brookner, a largely unknown queer Jewish artistic talent.