Last month, the Museum of the City of New York mounted Gay Gotham, an exhibition that tells the story of New York City’s thriving and influential queer cultural underground. Encompassing more than eight decades of history, Gay Gotham gathers art works, printed matter like novels and newsletters, and other ephemera to reveal how queer artists and queer social networks have impacted the cultural landscape of both the city and America more broadly. Presenting period-specific maps and documentary photographs, the exhibition locates and draws connections between queer icons and the “gayborhoods” they called home, allowing us to contemplate how past generations of LGBTQ people carved out a space for the queer culture we take for granted today.

I spoke with co-curator Stephen Vider about Gay Gotham, specifically why the exhibition focuses on the years between 1910 and 1995. Why not include the present moment of queer visibility, in which New York City is certainly an important player? For Vider and co-curator Donald Albrecht, there was something more powerful in exploring the period when gay culture was less visible, forced underground—but still somehow shaping American life.

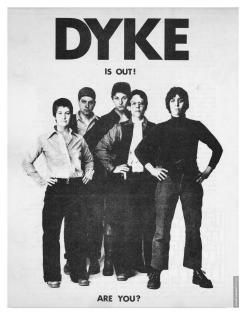

Liza Cowan and Penny House

“We decided to begin in 1910, the moment when you really start to see the emergence of queer communities in two neighborhoods in New York—Greenwich Village and Harlem,” Vider explained. “But we decided to end in 1995 because we felt that it was a turning point where what we call the mainstreaming of LGBT culture was beginning. Not that the underground went away at that point, but that LGBT culture was not confined to the underground entirely.”

Gay Gotham grounds its sprawling time range in 10 artistic figures: composer Leonard Bernstein; artists Robert Mapplethorpe, George Platt Lynes, Andy Warhol, Richard Bruce Nugent, Harmony Hammond, and Greer Lankton; writer Mercedes de Acosta; ballet impresario Lincoln Kirstein; and dancer-choreographer Bill T. Jones. And it literally draws connections between them. The exhibition floor is crisscrossed with painted lines indicating intimacies and influences between the exhibition’s subjects.

LGBT Community Center National History Archive

Gay Gotham celebrates how much New York’s queer community was able to accomplish during its most difficult times—its ability to “transcend oppression” through artistic collaboration. It contemplates how, even under duress, even in the closet, LGBTQ people like Leonard Bernstein, a creator of West Side Story, drew upon a network of queer cultural workers to produce work that defined American culture and still resonates with us today.

Walking through the exhibition, I was struck by how many of the faces on view are still part of daily conversation—particularly in queer circles, and especially among drag queens like myself.

An installation on Warhol and his entourage includes images of the fabled Candy Darling, immortalized in Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.” Just few weeks ago, I heard rising drag queen Judy Darling rhapsodizing about Candy Darling—her namesake—while discussing the importance of remembering and learning from our LGBTQ forebears and looking to them for inspiration. “Candy Darling really serves as a guide or guardian angel when it comes to dealing with my depression and anxiety,” Judy Darling told me. “At times I feel she is looking over my shoulder, making sure I don’t make the same mistakes.”

Courtesy of the Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, NY

The Gay Gotham catalog offers an even broader array of artists and cultural producers that touch contemporary gay life, including Mae West, whose 1928 Broadway production of Pleasure Man was raided and ultimately shut down by police for its depiction of drag queens. West and the 54 actors involved in her production were arrested and charged with indecency, adding to the provocateur’s already growing notoriety. West’s ties to queer culture, deeply rooted in New York, are still felt—she recently drew renewed attention when drag starlet Alaska Thunderfuck embodied her during a “Snatch Game” challenge on RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars.

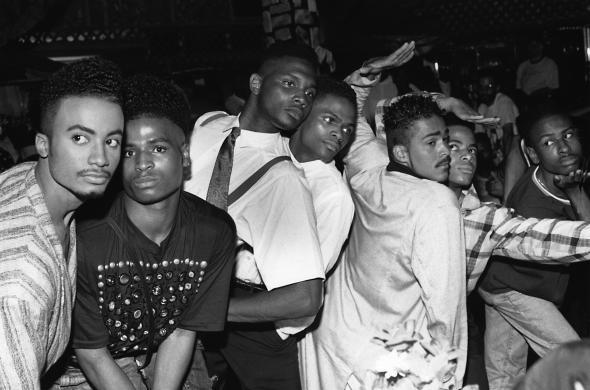

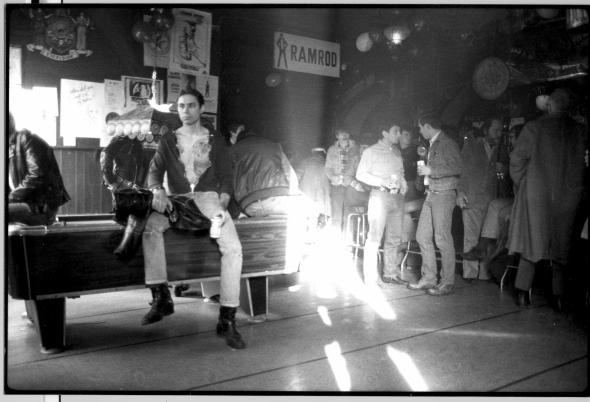

But Gay Gotham is not about icons alone. It also explores vitally important but overlooked moments in queer New York’s history. For example, most of us know that the West Village has been a safe haven for gays since the turn of the century—the neighborhood still looms large in the queer imagination as the cradle of gay culture and activism, despite its more recent gentrification. But how many are familiar with the similar haven that existed uptown?

The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

“There was no way to tell this story without also telling the story of Harlem,” Vider told me, pointing to a map of the queer-friendly bars and clubs that once existed along Seventh Avenue between 131st Street and 138th Street. In the 1920s, these streets offered popular but forgotten venues like The Ubangi Club, where famed performer Gladys Bentley “wore male attire and sang naughty show tunes,” as well as 20 other queer venues that, according to the catalog write-up, offered people “the chance to hobnob with the neighborhood’s lesbians and gay men.” The LGBTQ empire marked out by these hot spots has since dwindled to a handful of gay-friendly spaces, but the power of that moment is still felt in the work of the iconic artists and cultural figures who experienced it—James Van Der Zee, Carl Van Vechten, Richard Bruce Nugent, and more.

One of the most touching moments in the exhibition is a simple video installation that offers a rolling slideshow of photographs contributed by Gay Gotham visitors. The installation draws inspiration from “The Gallery of Extraordinary Portraits,” a 1928 exhibition celebrating interracial, gay, and artistic communities that artist Max Ewing installed in the walk-in closet of his studio apartment. How strange it is to think that such subject matter, once literally confined to the closet, can now be celebrated on the walls of a museum. And how good it is to see the story of queer life in this city recognized as part of the fabric of our national character.

Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York will be on display at the Museum of the City of New York through Feb. 26, 2017.