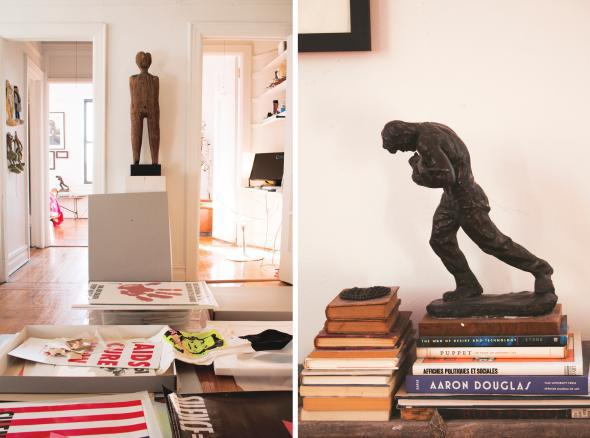

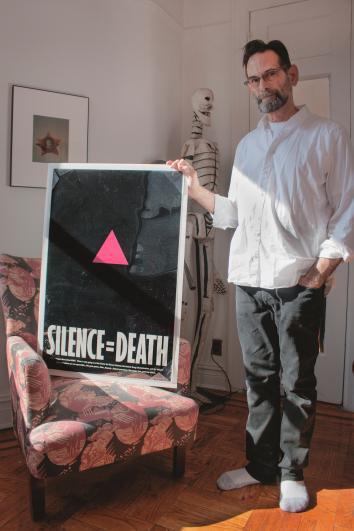

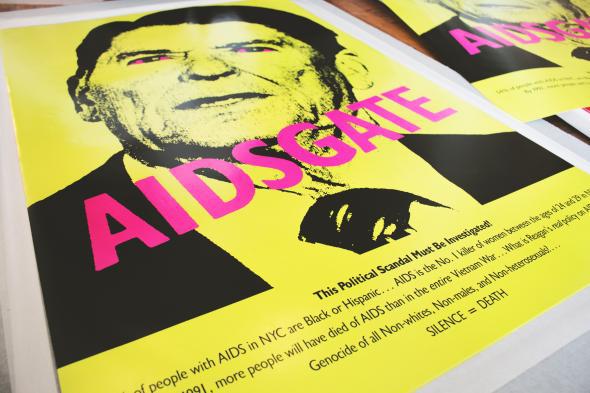

In a modest Brooklyn apartment, almost three decades of queer political art sits neatly organized in large, flat storage containers. Flipping through the seminal protest pieces—including the original “Silence = Death” poster—you can almost hear the chants. You can almost see the young men and women marching. But harder to picture would be the artist behind them all: Avram Finkelstein.

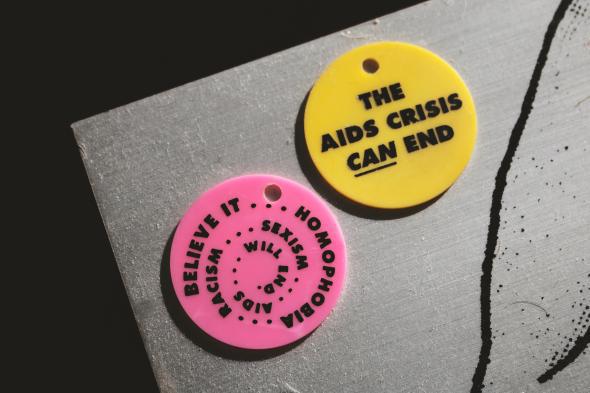

Avram’s art is pervasive, but rarely attributed. At 63, he’s dedicated his life to collective, public, and political art. He has either formed or participated in every major radical queer activist group, including Gran Fury, ACT UP, and the iconic Silence = Death collective. Now, he is a working artist running flash collective workshops around the country, in which he guides participants to craft a collaborative work to be mounted in a public space. These collectives address a range of issues, including one on immigration held at NYU, another about the Food and Drug Administration held at Yale University (the result of which was later circulated in Congress), and a recent one about bridging the HIV “viral divide” between people of different statuses. This last work, a GIF calling for “no walls between gay men,” will be projected during the opening of Art, AIDS, America at the Bronx Museum on July 13.

James Emmerman

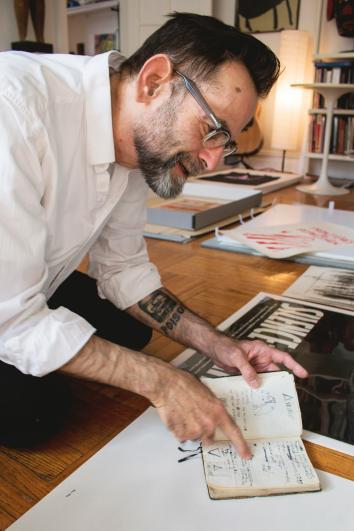

Avram is a dark-haired, solemn man with sharp eyes. He gave me a quick tour of his art-filled apartment when I visited on a Sunday afternoon last spring. He’d brought out the boxes of his work and was eager to get started. Soon, we were sitting on the living room floor in our socks, sifting through endless boxes of radical gay history and discussing what “queer” is and was, the history of Silence = Death, and the current state of queer political activism.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Starting broadly, how have you understood the term queer in the past?

Well, at the genesis of the queer “conversation,” it was simply a way in which we could refer to men and women at the same time. And then, of course, the term came to refer to a larger set of conversations. Academics began to do work around queer questions, and the word traveled and permutated. But I’ve identified as queer since 1987 simply because it was an expeditious way to refer to everyone I knew with one word.

But, technically, the conversation came out of the group ACT UP. It prompted the creation of a group called Queer Nation and another called Anonymous Queers.

Could you explain what ACT UP is?

ACT UP, the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power, was an AIDS activist organization that formed in 1987. It started in New York and eventually chapters formed around the world. We used direct political action to advocate on behalf of People living with AIDS, and pressured research institutions and drug companies to streamline access to life-saving drugs.

James Emmerman

What drove you to work in public art?

I’ve been thinking a lot about that recently. My folks were Communist Party members, and the whole family comes from political backgrounds. I went to the Museum School in Boston, which was essentially a political poster factory at the time, and graduated in 1973. But by 1979 the person I was building my life around, Don Yowell, started to show signs of immunosuppression, and he died by 1984.

I was completely pulled out of this art world trajectory and deposited into a terrible political moment.

James Emmerman

And is that when Silence = Death came about?

Kind of, I formed the Silence = Death collective after he died to help me cope. But we were a political collective, not an art collective. It was a space to talk about personal things, but the conversation would always end up political.

I remembered that in the ‘60s, the way people would communicate political messages that weren’t covered in the mainstream was through the streets with posters and manifestos. So I suggested to the six-person collective: “Why don’t we do a poster?”

And that’s where Silence = Death came from. But it was the queer community in New York that really created Silence = Death as a project.

The whole strategy behind the poster was that we wanted to speak to two completely different audiences simultaneously. It was meant to help organize the community around the politics of AIDS, but it also had to imply to everyone outside of the community that we were completely organized already. So it was this sleight of hand where we’re projecting authority but also asking questions.

And why the pink triangle?

The pink triangle is what they would put on gay men in the concentration camps of Nazi Germany. We were trying to figure out what kind of coded image gay people would look at and immediately know we were talking to them. This fit because of its historical significance.

Since we wanted to paste the poster alongside commercial and movie advertisements, we aimed to make sure it created its own space. We carved a “quiet zone” by adding the black, negative space around the triangle.

James Emmerman

How do you understand queer today? As you said before, the conversation has obviously shifted from its beginning. It seems like now; queer is where people go if they want to get away from the idea of defined identity. Is to be queer today to dis-identify in a sense?

Yes, queerness today isn’t about a specific identify, it’s become a way of navigating identity outside of power structures.

Was this the direction you thought the conversation would take?

No, because at the time the struggles were very different. I don’t think anyone really foresaw all the feminist work around identity that would bleed out into so many other conversations. But it’s not surprising if you think about it, because every conversation we have in terms of queer theory comes out of feminist critiques.

I’ve identified as queer since forever. But I know a lot of people who don’t, and if I ever suggest getting involved with a project that has the word queer in it, they won’t do it. Mainly because they are of a generation, older than I am, that fought against that word.

That’s the thing about identity, a lot of people of my generation now have very fixed ideas about what gender means based on struggles we had in the ‘70s surrounding gender equality.

So it’s not counterintuitive or surprising, but the question you asked was whether I saw it coming. I didn’t.

Are you happy with where it’s gone? Would you change it?

I wouldn’t change it all. The work my entire life is dedicated to is based in collectivity, and a key component to collectivity is listening. That’s what collectives are about; it’s not just about the declarative.

But I do have certain questions. A lot of the conversations today are within academia, and, I could be wrong, but I worry conversations that are academically based are also class-based. Because who can afford to go to school? Who takes gender studies? How do academic conversations apply to somebody who drives a cab for a living?

James Emmerman

Yes, that’s a part of the reason why I wanted to talk you about this. I’m interested in your work because it exists outside of academics. I think so much of the queer conversations today get lost in the ivory tower.

Do you know the mathematical figure of the Klein bottle? It’s a theoretical construction where the neck of the bottle goes into the body of the bottle. It’s like Mobius strip. It’s a self-contained system of logic. I think you could describe academia that way. If you’re not headed for a job in academia, or one where we describe academic or theoretical thoughts, then what use do those things have?

The reason I work collectively and outside of academia is because I believe art that isn’t about communication is about class.

I refuse to do work that’s only seen within a gallery or museum context, because I feel it shuts out every person who is not extremely well-educated about art. And I know tons of people who are incredibly well-educated about everything, but they still walk into a museum and have no idea what they’re looking at. That’s where this phrase: “I don’t much about art, but I know what I like,” comes from. It’s a way of navigating, but not really understanding, what you’re looking at.

So, how fucked up is it that the entire art world is constructed around this complex set of academic ideas that most people don’t have access to?

And you could say the same about queer conversations today. When it’s entirely based in academic language, I worry that the language alienates the very people much of those conversations are about.

James Emmerman

James Emmerman

What do you think will happen to queer art and artists as society progresses and, hopefully, becomes more accepting of deviation from the norm? Is that difference necessary as inspiration?

I think what you’re asking is parallel to the questions of the avant-garde—how do you maintain an otherness within late-stage American capitalism, or capitalism in general, where everything is commoditized? That’s a really good question, but the fact is, as long as there are power structures, there will always be Others.

James Emmerman

The idea that we can live in a classless society, that anyone can be president or anyone can make it, are the lies of the American mind. The fact is that very few people do that. It’s an institutional fantasy we all buy into that’s been very carefully marketed through many, many ways. It’s so pervasive, this fantasy, that we don’t even see it coming half the time. So, if you subscribe to the idea of the 99 percent, the majority of us are Others in some respect.

I think the idea of queerness as we’re talking about it at the moment, in academic circles, the idea of queerness as a way of describing otherness will always be true. There’s only room for 1 percent to rule the world. We can’t all rule the world, although, I’ve spent my life trying to figure out how we can.

And that’s what my work is about—it’s a battle, and you never stop fighting, and every time you figure out one way to navigate power structures, they figure out another way to absorb it, so it’s a constant, ongoing struggle.

James Emmerman

* * *

Finkelstein and I originally spoke in April of 2015, but after the Orlando massacre on June 12 of this year, his work seemed newly salient. I checked in for his thoughts on queer art and activism in the wake of Pulse.

So then what role does queer political action have today, especially in light of the Orlando shooting?

What Orlando tells us is something every queer person knows in their heart: Safety is an illusion. And being out is a declaration, even here in the “post-gay” 21st century. Being out is to register oneself through the use of one’s body, the queer body, and that is a quintessentially feminist gesture. Intersectionality is another gesture that comes out of feminist critiques, and the most meaningful conversations spurred by Orlando are the ones that pay attention to intersectional questions.

Interestingly, memes are spreading like wildfire across social media that refer back to the Gran Fury Kissing Doesn’t Kill and Read My Lips projects, both of which were earlier responses to the homophobic rage same-sex kissing has always caused, and likely always will. Silence = Death has also made the rounds on the internet in various iterations since Orlando. ACT UP has long been the gold standard for effective queer resistance, so many of the gestures that came out of the cultural production associated with ACT UP are still relevant, and up for reinvention.

So I’ve been flooded with emails asking me how I feel about people appropriating work I had a hand in. The answer is it brings me great solace. It’s the privilege of the young to reinvent the things they discover. Have at it.

James Emmerman

Update, July 18, 2016: This post has been updated to reflect the fact that while Finkelstein formed the Silence = Death collective, the entire group takes credit for the iconic image. The full membership included Finklestein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Lione, and Jorge Soccaras.