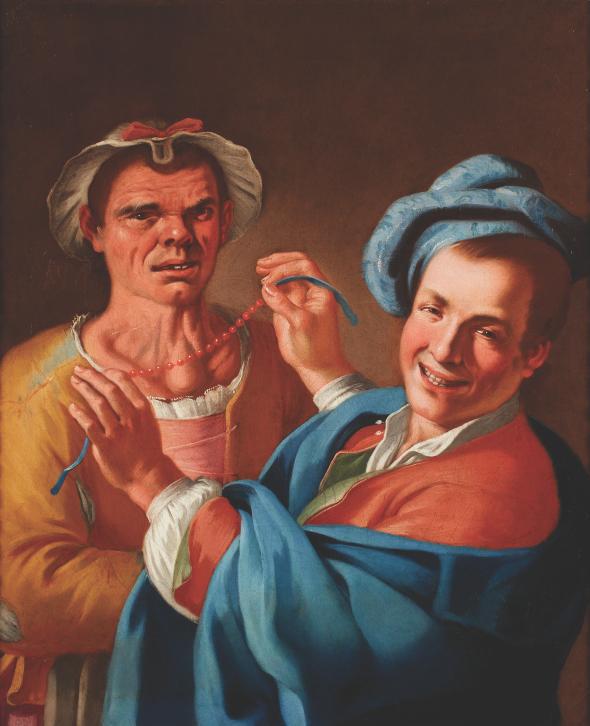

Dawson Carr had never seen anything like it. Carr, who serves as a curator at Oregon’s Portland Art Museum, was looking through a lineup of potential acquisitions in a sale at Sotheby’s New York when an unusual painting caught his eye. Bold, colorful, and strangely comic, the piece was a portrait of a male figure dressed in women’s clothes. The figure stands with a quizzical—almost pained—expression as a younger man fits him with a red coral necklace. The effect is both shocking and transfixing, an artifact from a history that is still emerging from the shadows.

Painted by Giuseppe Bonito, who was born in 1707, the portrait, known as “Il Femminiello,” depicts one of Naples’ femminielli, a class of male-bodied individuals who comprised a kind of “third gender” in 18th-century Italian society. Confined to the city’s Spanish Quarter, then one of Naples’ poorest neighborhoods, the femminielli were thought to confer good luck onto the households in which they were raised. People would even bring babies for them to bless.

“Il Femminiello,” which was painted sometime between 1740 and 1760, is one of the earliest instances of gender-nonconformity in art. Carr, who spoke over the phone about the piece, said that the painting “stopped [him] cold.” He said, “Images of real people cross-dressing are extremely rare.” In fact, Carr says that “Il Femminiello” wasn’t widely known when it was acquired by the Portland Art Museum earlier this year, primarily because so little is known about the lives of individuals who broke with gender norms in that era. “The definitive history has yet to be written,” Carr stated. “It’s probably going to be difficult … because it wasn’t written down.”

Bonito’s painting is one of only a handful of such representations during the period. One other work from this era made its way to London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2014. The piece was originally believed to be a Gilbert Stuart portrait of an unidentified British woman. (Stuart is most famous for painting the image of George Washington that graces the dollar bill.) Instead, the piece turned out to be a painting of the Chevalier d’Eon by Thomas Stewart, an artist active in London’s theatrical circles during the late 18th century.

Public domain, via Wikipedia

The Chevalier d’Eon was a figure of considerable intrigue. Also known by the cumbersome name of Charles Geneviève Louis Auguste André Timothée d’Éon de Beaumont, d’Eon managed the rare feat of being accepted as a woman in conservative 18th-century society; she was even championed as a leading feminist figure by Mary Wollstonecraft (the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women and mother of Frankenstein’s creator) and the poet Mary Robinson, who was known as “the English Sappho.” During her storied life, d’Eon fought in the Seven Years’ War and served as a spy for the king, infiltrating the Russian court in feminine dress.

Lucy Peltz, the curator of 18th-century portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, told the Guardian that the painting, called Chevalier d’Eon, offered a rare moment of historical visibility for the queer community. “One of the reasons the gallery was so keen to acquire the portrait is that [d’Eon] is such a fantastically inspirational figure and one of the very few historical figures that the gallery can represent that is a positive role model for modern LGBT audiences,” Peltz said.

Whether “Il Femminiello” portrays its subject in a positive light is open to interpretation, however. According to Carr, Bonito often worked in the genre known as pittora ridicula, literally, “ridiculous paintings.” Sotheby’s writes of these works, “In these pictures, artists chose subjects from the lower classes and depicted them (usually) in mildly amusing ways or situations, and often with moralizing overtones.” Although Carr notes that many pittora ridicula were “ribald” and “meant to make you laugh,” he contests the notion that the femminiello depicted in this painting is an “object of derision.” “I have to say I don’t see that,” he said. “I see it much more neutral.”

According to David Getsy, the problem with interpreting works like “Il Femminiello” is reconstructing the history when so little is known about people who lived outside of the confines of gender in the 18thcentury. “The historical record has so little in it around evidence of transgender lives—or what we would now call transgender lives—and the evidence we do have is couched in oppression and negativity,” Getsy, a professor of art history at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago,* told me in a phone interview. He notes that it’s important not to project the identity politics of the present onto the past, when labels like “trans” and “nonbinary” weren’t options.

For Getsy, a painting like “Il Femminiello” is a reminder that history often acts as a means of erasure, especially when it comes to marginalized identities. He said, “Any evidence [of such works] is just a part of a larger historical archive that may not have survived.” Nonetheless, he believes that paintings like “Il Femminiello” represent a “remarkable piece of singular evidence that there were culturally sanctioned and official forms of gender nonconformity,” even if many of those histories may be lost.

Public domain/Wikipedia

Zackary Drucker, a trans visual artist and producer on the Amazon show Transparent, notes that despite patterns of erasure, there are many examples from history that speak to the complexities of gender. Drucker mentioned Sleeping Hermaphroditus, an ancient Greek statue on display at the Louvre in Paris. The figure, based in the country’s mythological tradition, is depicted with an intersex body. “It’s a woman reclining, and when you see it from the front, she’s on her side, and it’s her backside, and she’s horizontal,” Drucker explained. “And then when you walk around to the other side of it, she has a penis.”

While Carr cautions against looking at “Il Femminiello” as representative of any kind of early notion of trans acceptance, Drucker suggests that such works are the tip of the iceberg in how gender operated in the 18th century, and even before. “The binary is a Victorian holdout,” she said. “There have been times of fluidity that we tend to forget about.” She points to the history of men playing female roles in Shakespearean theater, as well as Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa,” which Drucker describes as a “self-portrait of him as a woman.”

David Getsy believers that fostering further LGBTQ visibility in art will be crucial for historians. “There are many people who are trying to attend to these erasures and find these histories, because they are important to put in place, and they are essential to know that one’s not alone,” he said. “There’s a long history of people who have fought the same fight.”

Drucker added that uncovering histories like those of the femminielli is important for the LGBTQ community itself. “Telling these stories offsets the misconception that trans people are a youth phenomenon or that trans people are a community that’s popping up out of nowhere,” she said. “The ground has to crack and fill up with bodies and then somebody stands on those bodies until it cracks again, and that’s what history is. You need to have enough generations of people to feel like you’re part of something bigger.”

*Correction, July 11, 2016: This piece originally misstated the institution where David Getsy is a professor of art history.