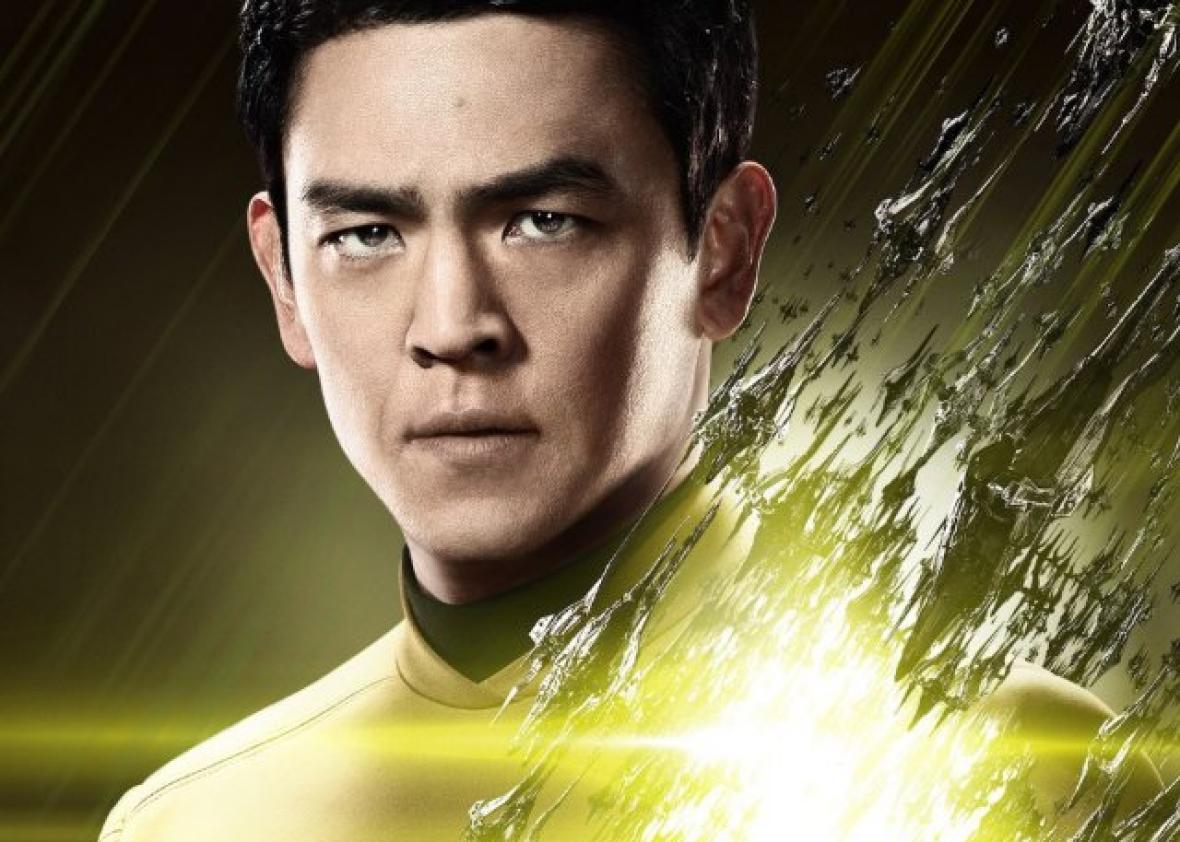

Star Trek Beyond doesn’t premiere in theaters for another two weeks, but already fans are being treated to a rather stunning exchange of phaser fire. As my colleague June Thomas covered on Thursday, John Cho—who plays Lt. Hikaru Sulu in the reboot films—revealed that his character is gay, a fact that will reportedly be indicated by a brief, straightforward scene showing him with a husband and daughter. This bit of characterization was included, according to writer Simon Pegg and director Justin Lin, as a tribute to George Takei, who famously originated Sulu in the first Star Trek TV series and who, after coming out in 2005, has become a vocal advocate for LGBTQ equality. But there’s a problem: Takei doesn’t think Sulu should be gay. In fact, he’s been inveighing against the choice behind the scenes for months now and is dismayed that his wishes went unheeded.

In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter, Takei painted the decision as a betrayal of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry’s original vision. “I’m delighted that there’s a gay character,” he said. “Unfortunately, it’s a twisting of Gene’s creation, to which he put in so much thought. I think it’s really unfortunate.” While many have interpreted Takei’s surprising resistance to having a gay Sulu in the new movie as an overzealous commitment to preserving the canon (something not unheard of among Trekkies), reading his reasoning and the subsequent response from writer Simon Pegg, it’s clear that there are far more substantial issues in question than a nerdy investment in fictional coherence—issues that get at the heart of what being “gay” means today and what queerness may or may not look like in centuries to come.

Starting with Sulu himself, Takei says he told Cho and the creative team that making Sulu appear to have been closeted until now was a mistake. From the Hollywood Reporter interview: “I told him, ‘Be imaginative and create a character who has a history of being gay, rather than Sulu, who had been straight all this time, suddenly being revealed as being closeted.’ ” He also pointed out, wisely, that the closet would surely be a strange concept to someone living in Star Trek’s utopian vision of 23rd-century Earth anyway. I’ll pick up on that in a moment, but it’s Takei’s phrase “a history of being gay” that’s most immediately relevant.

Analyses of this spat so far have patiently explained that because the events in Beyond and the previous two reboot-era movies technically take place before the original TV series—in which Sulu had no romantic relationships and which in any case occurs in a separate timeline due to J.J. Abrams’ mastery of quantum physics and storyboard acrobatics—there’s no need to necessarily view him as closeted. You can resolve the temporal thicket the reboot created in one of two ways: Sulu’s sexuality changes depending on the universe or he just got quiet about it in later appearances for some reason (e.g., filming in the 1960s). Pick a poison if you like, but I don’t think continuity is exactly what’s bothering Takei. The thing is, having a “gay” character doesn’t mean much—either narratively or in terms of diverse representation—if what marks him as that is the laziest of signifiers, if, in other words, he does not have a rich and well-articulated “history of being gay.” Assuming Sulu reads as straight in every other way besides the photo of a man on his console, and if that photo is only shown in passing, have you really done anything worth praising?

It would, of course, be near impossible to imbue an established character like Sulu with a meaningful gay history, a characterization that marked gayness as a serious part of his life and cultural expression—which is why I think Takei’s suggestion that a new character be created makes much more sense. But Pegg had reasons for resisting that route: “We could have introduced a new gay character, but he or she would have been primarily defined by their sexuality, seen as the ‘gay character,’ rather than simply for who they are,” he said in a statement, “and isn’t that tokenism?” The film’s creative team, says Pegg, did not want sexuality to be their queer character’s “defining characteristic.” And just like that, Pegg teleports the it’s a small part of me identity ideology of our time two centuries into the future.

I have written at length about the pernicious logic of “small part” thinking around queer identity, so I won’t rehash that here. Suffice to say, including a gay character in your story for whom gayness is nothing more than a boring and rarely mentioned biographical detail might not be the greatest of achievements. In fact, it might suggest that you’re not really superinterested in including queerness in your story-world after all but, rather, are looking to check a (now relatively safe) box on the good progressive representation worksheet. In fact, it might suggest that you are enacting the very “tokenism” you say you want to avoid.

It might. Anyway, it doesn’t sound like the newly out Sulu is going to be gaying up the Enterprise in any appreciable way—which brings me to the next point: Are we really sure there haven’t been gay or queer characters on Star Trek before? Because this is what they’re saying. Pegg: “[Takei’s] right, it is unfortunate, it’s unfortunate that the screen version of the most inclusive, tolerant universe in science fiction hasn’t featured an LGBT character until now.” Admittedly, I’m not a Trek completist. My engagement, by dint of my age, was mostly centered around Voyager and Deep Space Nine with considerable forays into TNG and dabbling in the original series and the earlier movies. But incomplete knowledge stipulated, I recall recognizing a number of obviously queer characters in the shows. I mean, does no one remember Q? He’s essentially Oscar Wilde imbued with the cosmic omnipotence of the Continuum. And what about Voyager’s holographic doctor? I don’t recall him having a husband (simulated or otherwise), but he was definitely a massive photonic queen. And that’s just off the top of my head.

The point is, the idea that a same-sex relationship, or even same-sex sex, is the be-all-and-end-all of queer representation is so horribly basic. Add all the culturally queer characters to the reams of fan fiction about Tom Paris teaching Harry Kim how to work the warp throttle, and it’s quickly apparent that Star Trek was hardly ever straight. You just had to be imaginative enough to know what you were seeing.

Of course, all this squabbling, mine included, stems from another failure of imagination: that our 2016 notions of sexual and gender identity would or should be relevant to someone living in Roddenberry’s 2216. It bears repeating, daily, that gay, not to mention queer or LGBT, are historically specific and culturally contingent inventions. Same-sex desire and gender variance have existed forever, but the categories we organize our lives, politics, and subcultures around right now are by no means stable or built into nature. I know that runs counter to our “born this way” security blanket, but it’s the truth.

Elsewhere in his response to Takei, Pegg spoke of the “magic ingredient [that] determines our sexuality” varying between timelines for Sulu, adding, “I like this idea because it suggests that in a hypothetical multiverse, across an infinite matrix of alternate realities, we are all LGBT somewhere.” There are many ways one could describe this statement, but I will settle on misguided. LGBT-ness is not some kind of transdimensional force that graces certain lucky individuals at random points within the multiverse. It’s a peculiar and incredibly specific construct that seems more or less useful for finding community and advancing activism in a moment when “rights” may only be afforded to well-defined groups. But it’s also often dangerous for those forced to adopt it in the pursuit of social legibility, it’s hardly descriptive of the range of sexual and gender diversity human beings are capable of, and it’s certainly not where I think we want to end up on the quest for freedom of human expression. And yet, here we are arguing about whether a character in probably the most blended, utopian, forward-looking fictional universe ever created is gay.

In the end, it’s really this—that Pegg, Takei, and the rest of us insist on transposing our contemporary identity politics onto a landscape that doesn’t really need them—that’s the most dispiriting part of this whole fracas. I think that back when I spent my Saturday evenings with Capt. Janeway and her crew adrift in the Delta quadrant, I just assumed that by the time we got out there, everyone would be a lot more creative about sex and gender expression. Sure, difference and preferences would still exist, but when you’ve got a holodeck at your disposal, there’s no reason not to explore. In 2016, we still need our categories and the cohesion they allow. We, as the Sulu hullabaloo shows, are still profoundly earthbound. But after warp drive? After first contact? After we can really feel how massive the universe is and how small we are by comparison—will we really need or even want LGBTQ anymore? I sort of hope not. We’re still a long way off from that world, to be sure. But in the meantime, it would be nice if we freed our science fiction to make the leap for us.