The world has known few superstars whose personas could match the gender-fluid extravagance of Prince, who died on Thursday at age 57. The pop and R&B icon inlaid his albums with brazen pansexuality and gender norm coquetry—provocations made all the more potent by his staggering talents as a singer, hook-writer, and guitar shredder. Years before the leaders of the gay and lesbian community began to embrace a more nuanced, less binary notion of queerness—and decades before transgender and genderqueer politics became mainstream topics of interest—Prince presented a living case study in the glorious freedom a world without stringent labels might offer.

“I’m not a woman. I’m not a man. I’m something that you’ll never understand,” Prince sang on 1984’s “I Would Die 4 U.” He was right—few could claim to fully grasp Prince’s easy embodiment of both maleness and femaleness. His schooled evasion of conventional classifiers made him endlessly fascinating. The cover of his 1988 album Lovesexy offers a classic expression of the seemingly incongruous yet thrilling gender bricolage at which he excelled.

Prince’s coy, sensuous form in a larger-than-life sea of yonic flowers telegraphs femininity. But he’s showing off his masculine features, too: Prince covers his nipple as if it were a breast, but exposes a full chest of hair. His legs look smooth and shaven, but a John Waters moustache sits above his full lips.

Like his gender-bending predecessor David Bowie, Prince was flamboyant in both his masculinity and femininity. He wielded his outrageous guitars like extensions of his manhood while vamping under winged eyeliner and plentiful jewels. He even bragged that his traditionally feminine features lent him a special sexual power. “The way I wear my knickers around this booty tight / Make a sister wanna call me up every night,” he sang on “Prettyman” in 1999. “Everywhere I go, people stop and stare / They just wanna see me swing this pretty hair.” Prince didn’t just disregard the boundaries of gender and sexuality: He kicked straight through them in platform heels, gyrating his very visible bulge in naysayers’ faces for good measure.

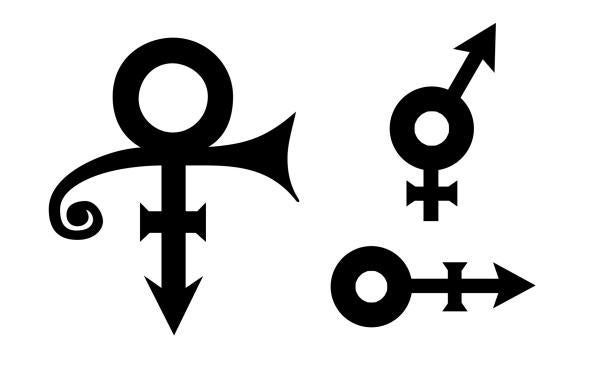

This kaleidoscopic conception of gender became integral to the very core of his identity. When Prince abandoned his stage moniker in favor of “the Love Symbol” in 1993, he included elements of both the Mars and Venus, or male and female, iconography in his design. Today, similar signs are used to designate trans, genderqueer, or intersex people.

Slate photo illustration.

Some listeners took one of Prince’s tracks, 1987’s “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” as a sideways entrée into issues of trans identity. “If I was your girlfriend / Would u remember 2 tell me all the things u forgot / When I was your man?” he sang. “Would u let me wash your hair / Could I make u breakfast sometime / Or then, could we just hang out, I mean / Could we go 2 a movie and cry together? … I mean, we don’t have 2 make children 2 make love / And then, we don’t have 2 make love 2 have an orgasm.”

For fans, Prince’s expansive presentation of gender and sexuality offered promise of a more honest, open existence. “I became unafraid to display the many stereotypically feminine qualities that were within me,” StainedGlassBimbo, a self-described heterosexual man, wrote on a Prince fan forum. “[He showed me that] you don’t have to be a masculine in order to be a man.” Another message board commenter marveled at Prince’s macho braggadocio wrapped in the trappings of the fairer sex: “Here was a man wearing lace and jewels—and he’s singing of having sex with women in ways I didn’t even know existed!”

Prince’s androgyny and unbridled sexuality inspired generations of musicians, too. Adam Levine, who’s covered the Purple One and called the artist “limitless…fearless, and unselfconscious,” posed nude for Cosmo U.K. in 2011 with wife Behati Prinsloo’s hands covering his junk. The image echoed a Notorious cover Prince did decades earlier, wearing a bouffant, hoop earring, fuzzy purple coat, and the wandering hands of a female lover. In 2006, gay musician Rufus Wainwright wrote in the Guardian that Prince’s genderfuckery is still unmatched in modern pop music. “It feels weird talking about Prince as a gay icon now, but you have to applaud a black man in the American record industry who could be so playful with androgyny,” Wainwright wrote. “Justin Timberlake wouldn’t do that. He is a marine dressed as a pop star.” In memoriam, on Thursday, bisexual singer and rapper Frank Ocean wrote his own heartfelt tribute:

He was a straight black man who played his first televised set in bikini bottoms and knee-high heeled boots, epic. He made me feel more comfortable with how I identify sexually simply by his display of freedom from and irreverence for obviously archaic ideas like gender conformity.

Though Prince openly embraced a fluid concept of gender, his personal sexuality kept everyone guessing. His lyrics demonstrated a kind of omnisexual thirst for pleasure, though certain lines led fans to wonder if he was some flavor of queer. On 1981’s “Controversy,” Prince addressed his multiracial background along with his sexuality: “Am I black or white? Am I straight or gay?” In 1980’s “When You Were Mine,” he sang of sleeping in bed with a female lover, but with her new man in between them. Prince sometimes told curious interviewers that he was straight, but more often, he hedged with a shrug or a “Why does it matter?” That didn’t stop even straight-identified men from lusting after him. On a forum called Testosterone Nation—in the muscle-building way, not the transgender hormone therapy way—a user by the name of byukid neatly summarized the feelings of thousands of hetero dudes who found themselves drooling in the audience of a Prince show: “I would go gay for Prince, except I’m not entirely sure Prince has a gender.”

But Prince probably wouldn’t have returned the sentiment. He became a Jehovah’s Witness in 2001 and began to sound more vocally homophobic as he aged. The New Yorker asked him about his positions on gay marriage and abortion in 2008; Prince “tapped his Bible” and said, “God came to Earth and saw people sticking it wherever and doing it with whatever, and he just cleared it all out. He was, like, ‘Enough.’ ” In 2013, the artist dropped a track called “Da Bourgeoisie” that contained lyrics many deemed anti-gay or bi-phobic: “Yesterday I saw you kickin’ it with another girl / You was all wrapped up around her waist / Last time I checked, you said you left the dirty world … I guess a man’s only good for a rainy day / Maybe you’re just another bearded lady at the cabaret.”

Still, Prince’s gender fluidity and sexual ambiguity granted a kind of permission for future musicians, queer and otherwise, to explore new means of expression of the self and sexuality. That he was simultaneously a beloved gay icon and perhaps an anti-gay proselytizer is just one ripple in the vast sea of contradictions that made Prince such a spellbinding artist, a virtuosic performer of music and gender alike.

Read more from Slate on Prince.