Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, a stylish new documentary premiering Monday on HBO, profiles the life of controversial photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Specifically, the film focuses on the development of the artist from adolescence to adulthood, a period during which he struggled to define his artistic voice. Directors Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato identify a key aspect of Mapplethorpe’s psychology, outlining a battle between “good” versus “evil”—or really, straight vs. gay. Having had a religious upbringing in Floral Park, New York, the photographer took many years to fully embrace his homosexuality, and with it, the gay leather aesthetic that would make him famous. Unfortunately, Look at the Pictures fails to understand how this conflict—and Mapplethorpe’s intense ambition to resolve this conflict through his photos—enhanced the artist’s work.

This misreading depends upon the omission of key moments of Mapplethorpe’s life. In the late ’60s, his then-girlfriend Patti Smith left him, and he was distraught. He threatened to “turn homosexual” if she didn’t return. This was the first outward acknowledgment of Mapplethorpe’s internal struggle with his sexuality. In Mapplethorpe: a Biography, author Patricia Morrisroe explains, “What Mapplethorpe had lost was his last defense against his homosexuality, and without Smith serving as a ‘wife,’ he finally had to grapple with the true nature of his sexual feelings.”

Mapplethorpe left for San Francisco as a result of the breakup. “There’s freedom there,” he explained, according to Smith’s account in Just Kids. “I have to find out who I am.”

In the 1960s, San Francisco was synonymous with sexual tolerance in the United States. The gay community had become increasingly visible there as homosexuals renovated Victorian homes and opened shops, bars, and restaurants in the Castro. This, coupled with the surge of hippies in Haight-Ashbury, made San Francisco the perfect refuge for the young artist intent on sorting himself out.

Upon Mapplethorpe’s return to New York, Smith describes him as “both triumphant and troubled.” But the San Francisco sojourn marked a major turning point in his life: He began his first male relationship with a boy named Terry. “It was like it happened overnight,” explains Smith. “The gay thing wasn’t there, and then suddenly it was.”

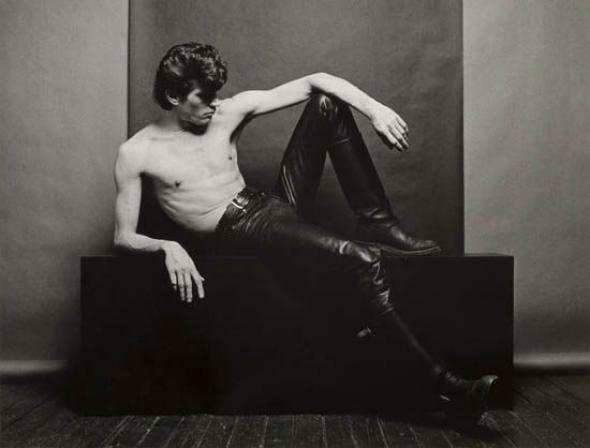

Mapplethorpe quickly became obsessed with his emerging sexuality and embraced all things homoerotic. His desire found its way into his art as he began making collages out of gay pornography. At the same time, a new form of homoeroticism had been emerging in gay culture influenced by the graphic art of Tom of Finland, defined by men sporting black leather jackets, motorcycle caps, and knee-high leather boots. This new image celebrated a kind of hypermasculinity and challenged more stereotypical, effeminate notions of homosexuality—in turn making it easier for some men to accept their sexuality. Morrisroe quotes Mapplethorpe: “There was no going back. I had found my form of sex.”

The leather subculture held great appeal for Mapplethorpe, serving as a space in which to indulge in his sexual difference while shedding those saintly expectations imposed on him as a child—and eventually all family ties entirely. Soon, pictures of men in Harley-Davidson motorcycle caps and leather pants appeared in his collages.

Marcus Leatherdale / HBO

Mapplethorpe soon realized that he was in a position to document the 1970s gay BDSM scene. He returned to San Francisco in order to gain the appropriate connections that would allow him access to the “leather men” he wanted to feature in his work. He approached Jack Fritscher of Drummer magazine, a national publication for gay leather enthusiasts, which celebrated homomasculinity. “Robert figured if he could get a cover of Drummer, men would give in quicker and allow him to photograph them,” Fritscher told Morrisroe. He eventually got that cover.

In a recent interview, Fritscher described facilitating Mapplethorpe’s entrée into the San Francisco leather scene to me: “I assisted him at work in the Twin Peaks condo where I set up a shoot of my other lover, physique champion Jim Enger. I drove him in my rugged 1969 Toyota Land Cruiser to scout the cement bunkers on the Marin Headlands for the ‘piss-photo’ shoot of ‘Jim and Tom, Sausalito.’ I vouched for him when he wanted to shoot my playmate Cynthia Slater in the dark dungeon of the Catacombs fisting palace. None of those photos would exist had he not come to San Francisco with MDA, poppers, and flowers in his hair.”

Mapplethorpe’s success seemed to grow in concert with his self-acceptance and confidence. Viewed ungenerously, his artistic ambitions could easily be oversimplified as a selfish pursuit of fame and success—a trap into which Look at the Pictures regrettably falls. In the film, we witness sentimental anecdotes from family, friends, and colleagues about this selfishness that seem somewhat petty when talking about what it took for such a talented artist to do his work. At one point, Marcus Leatherdale, an ex-lover, is read an unflattering letter that Mapplethorpe had written about him, which then provokes more negative sentiments.

To be sure, Mapplethorpe made compromises that many ordinary Americans would find questionable. But as he fully reconciled himself to his sexuality, perhaps this singlemindedness had less to do with greed and more to do with the pursuit of his true self through art. “The whole point of being an artist or making a statement is to learn about yourself. I think that’s the most important part,” says Mapplethorpe in the film. “The photographs, I think, are less important than the life that one is leading.”

Despite its flaws, Look at the Pictures—thanks to the broad reach of HBO—will deliver a significant part of queer history to viewers who may never have learned about it otherwise. Still, it’s unfortunate that the filmmakers failed to grapple with the role sexuality played in pushing the artist to define his vision. He overcame a grueling conflict between upbringing and desire that still imprisons many gay men in America today. He searched for his soul at all costs and found it—to the benefit of art history and gay history alike—in the refuge of his work.