As a writer who occasionally has reason to work with primary source documents in archives, I can vouch for the pleasures that come with handling the past directly. For example, when I wrote my long-form piece on homosexuality and gay cultural identity last year, I spent a chunk of time in the New York Public Library’s LGBT collections. It was thrilling—in a quiet, dusty sort of way. Of course, I was lucky enough to live in New York and have credentials to access those materials; many other interested folks, from students to independent scholars to history buffs, might not be so fortunate.

Which is why a recently launched project from Gale, the library resource provider within Cengage Learning, is worth noting. Under the title the Archives of Human Sexuality and Identity, the company has partnered with the NYPL, the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and other collection-holders around the country and world to create a digital archive that will make researching and experiencing queer history easier for everyone.

The digitization work is being completed in stages; the first, just-released phase covers LGBTQ history and culture since 1940 and already comprises about 1.5 million pages of searchable content. According to leaders of the project, future installments will likely look to earlier time periods; a plan is currently being formulated by an advisory board staffed with historians, librarians, activists, and other stakeholders. The current materials cover contributions from larger institutions as well as smaller, often ephemeral organizations and publications. They also include letters and papers from individuals. The project description continues:

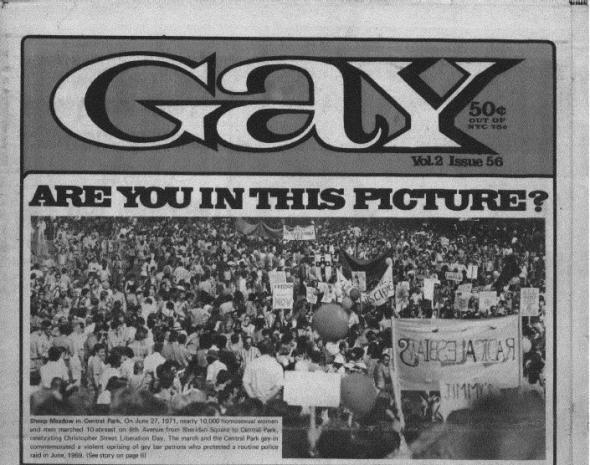

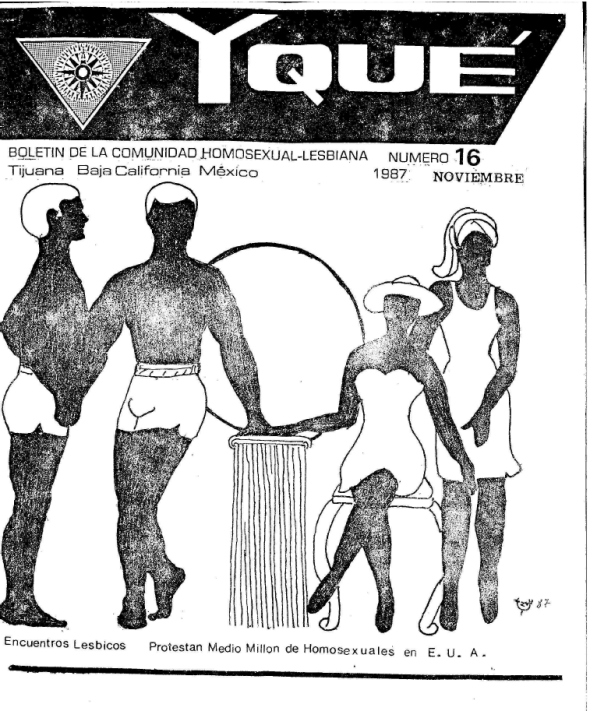

The archive illuminates the experiences not just of the LGBTQ community as a whole, but of individuals of different races, ethnicities, ages, religions, political orientations, and geographical locations that constitute this community. Historical records of political and social organizations founded by LGBTQ individuals are featured, as well as publications by and for lesbians and gays, and extensive coverage of governmental responses to the AIDS crisis. The archive also contains personal correspondence and interviews with numerous LGBTQ individuals, among others. The archive includes gay and lesbian newspapers from more than 35 countries, reports, policy statements, and other documents related to gay rights and health, including the worldwide impact of AIDS, materials tracing LGBTQ activism in Britain from 1950 through 1980, and more.

Archives of Human Sexuality / Gale

The importance of individuals having access to these materials through local and university library subscriptions cannot be overstated. For many queer people, looking up homosexual or transgender at the library is a first step to self-knowledge—it certainly was for me—and it’s one that’s usually met with somewhat frightening clinical descriptions. With access to this resource, searchers will find themselves awash in a much richer—and inspiring—history than they might otherwise have encountered.

And those encounters can indeed be moving. At a recent launch event in New York, Ray Abruzzi—a Gale vice-president and publisher behind this project—and I took a spin on the platform. I suggested looking up Stephen Donaldson, the man who founded the nation’s first queer student organization at Columbia University, my alma mater, in 1967. We quickly found a scan of the original typed manifesto for the “homophile” group, which, among other things, vehemently contested the idea that homosexuals were in any way medically or psychologically disturbed. The American Psychiatric Association would not confirm that truth until 1973; here was one of our ancestors speaking it boldly at a moment when almost everyone, including many homosexuals, disagreed. This kind of discovery would be functionally useful to researchers, students, and journalists like myself—but that night, I met Donaldson’s words simply and gratefully, as a gay man who benefited from them decades later. Not bad for a few clicks through a database.