If a lesbian writes a book, but no man reads it, does it actually exist?

It may sound ridiculous, but this tree-falling-in-the-forest analogy will feel all too apt to lesbian authors, whose systemic exclusion from cultural recognition and mainstream success has a long history and continues apace. These days, though, the exclusion isn’t so much due to blatant homophobia as it is to something more pernicious: So much of what creative queer women produce just isn’t seen, at least not by the people who determine what is culturally valuable.

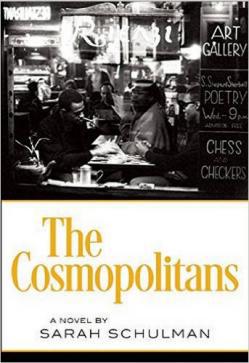

“It took 13 years for this to be seen,” lesbian writer and activist Sarah Schulman said recently, speaking about her incredible new novel, The Cosmopolitans. A modern-day retelling of Balzac’s Cousin Bette set in Greenwich Village in the late 1950s, The Cosmopolitans could—and should—launch Schulman into the mainstream.* It would be a success story comparable to that of Eileen Myles’s so-called “renaissance” in 2015 with the publication of I Must Be Living Twice. When I asked her if she thought career success would’ve been more immediate were she a man, Schulman nearly spat out her water: “Is that a joke?” Taking a breath, she more calmly replied, “I mean, that’s my problem. If I were a man or if I were straight, or if I had no lesbian content, I’d be more successful.”

This observation is a matter of fact for Schulman, author of seventeen books, both fiction and nonfiction, and countless plays. She may be a renowned figure of the queer firmament—from her activism with ACT UP, to her recent involvement in the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement in support of Palestine, to her role as both teacher and mentor to innumerable creative queers—but she remains largely unknown in the mainstream.

Schulman remains on the margins largely because of her commitment to truth: Take any one of her books—from her nonfiction like Ties That Bind: Familial Homophobia and Its Consequences (2009), The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination (2012), or the forthcoming Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair; to her fiction like The Cosmopolitans—and you’ll find a mind doggedly committed to describing the world as she sees it. But this is not truth with a capital “T.” For Schulman, truth is not absolute; instead, it unveils itself in the details. “I believe in the simultaneity of realities, complexities, and contradictions,” she explained. “So, [telling] the truth means reveal all the contradictions, all the flaws, and all mistakes. The truth not a magic answer—it’s the revelation of the nuance that is the truth.”

In The Cosmopolitans, Bette personifies truth in the way Schulman defines it. She is a queer, middle-aged white woman who demands that others, specifically her best friend Earl (a middle-aged, closeted, gay black man), come face-to-face with the truth about themselves and take responsibility for their actions. This demand—what Schulman has characterized in her writing as an ethical framework of accountability—is what makes Bette unbearable to everyone in her life. Like Balzac, Schulman deliberately crafts psychologically complicated—and not entirely likable—characters. This level of realism, she conveyed, has always been a critical component of her writing, incorporated in an attempt to overcome what she described as the “tyranny of positive images” of LGBTQ and minority characters.

Bette and Earl are neighbors who live in a Greenwich Village apartment building in 1958. In many ways, they are all each other’s got: a middle-aged odd couple in the “misery loves company” mold. Their friendship ruptures when Bette catches Earl in a lie—but an understandable lie he cultivates in order to live in the world amid the racism and homophobia of 1950s America. “The world … made me desperate,” Earl confesses to Bette, “And you were the only one I could affect. So, I made you desperate.” Because Bette’s modus operandi is truth-telling, she consequently becomes a threat to Earl: “When you’re lying, your greatest enemy is the person who reveals what’s true,” Schulman explained.

The Cosmopolitans was originally conceived as a play that was ignited by her own perception of strands of queerness when she read Cousin Bette as student at the University of Chicago in the 1970s. “I start out as a lesbian intellectual in an institution before queer studies, queer theory, or anything, and glomming onto one sentence because of something a professor said, holding it for years,” Schulman said. “Then,” around 2003, “working with a lesbian actress [Roberta Maxwell], who ends up not doing the play; then the play being too queer,” she continues, explaining that the play was never produced because the potential producer couldn’t understand the type of queer, New York City relationship Bette and Earl had. Confident the story was good, Schulman then turned the play into a book via a deliberate engagement with James Baldwin’s In Another Country, which served as a model for examining New York City relationships “in a pre-gentrified New York, where everything is affordable and people are really mixing.” The critical difference for Schulman was to write about women, and to incorporate their narrative point of view.

Finally, she added, somewhat defeated, “for three and a half years nobody would publish the book.”

This narrative represents the trajectory of so many queer works by lesbians—take the recent critically acclaimed Todd Haynes’ film Carol as a case-in-point. The novel upon which it’s based, The Price of Salt, was written in 1952 by Patricia Highsmith (originally under a pseudonym); after she took it up in 1997, screenwriter Phyllis Nagy struggled for almost 20 years for her script to make it to the screen. Not because Nagy was lazy—because no one would fund it.

Drew Stevens

Schulman knows that mainstream success is “arbitrary” and in part dictated by how well her writing can be commodified. As an out lesbian that writes stories primarily about lesbians and other queer minority subjects, she is keenly aware that chances of this are slim. “Before Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, in 1992,” she explains, “if you were out personally you were doomed. After that, you could be out personally as long as you didn’t have primary lesbian content in your work. But, to have actual lesbian content, as [LGBT activist] Urvashi Vaid said, is ‘the kiss of death.’” In Schulman’s mind, the lesbian writer consequently has two options: to write queer content or to not write queer content. “It’s the difference between the mainstream and the subculture,” she said.

She qualified this division when reflecting on the mainstreaming of the LGBTQ community, asserting that the commercial and mainstream requirement for success is focusing on the family: “Everything queer right now that is being accepted is about queer family,” she emphasizes, listing off “Transparent, Fun Home, The Argonauts, and even Carol,” as examples. Speaking of Carol, she elaborated, “In the original novel, Carol is much more ambivalent about her child. [However,] the film made her more involved with her child.”

Women authors who reject the demands of the market risk the scarlet N—for niche—which renders them as not worthy of financing, distribution, critical attention, and accolades. This disturbing disparity was made legend by Cate Blanchett in her 2014 Oscar speech, when she chided the idiocy thinking of women’s creative work as somehow specialized: “those of us in the industry who are still foolishly clinging to the idea that female films with women at the center are niche experiences. They are not. Audiences want to see them, and in fact, they earn money. The world is round, people.” For literary lesbians, the rejection of our work as “too niche,” amounts to a publishers’ intuition about a work’s commercial viability—or to quote Eileen Myles: “statistically they’re telling you how many people eat pussy without saying that.”

For Schulman, as for women in general, the everydayness of this type of rejection is infuriating. “Men my age are very sexist,” she said very matter-of-factly. “As long as men my age are controlling things, people like me won’t get anywhere.” Schulman continued: “I’ve gone through my life with people saying to me, ‘You are soooooo smart!’ No one says to a man, ‘You are soooooo smart!’” Her intelligence, she observed, “makes people angry, and it threatens them—and then it makes people read you as angry. You know,” she concluded, “I’m supposed to be inferior, and the fact that I’m not makes people very upset.”

In many ways, Schulman is like her character, Bette. Uncompromising. Unapologetic. “Facing the truth is what makes us fully alive,” is Bette’s observation—yet it is also Schulman’s. For the writer and her character, truth is the quintessence of humanity. The question is, what’s the point of all this honesty if no one’s listening? Valerie, Bette’s coworker and crush, tells Bette, “You are so smart. You have so many strengths. And yet, you can’t make your life work. After some serious study and consideration, I finally have figured out why.” Valerie then dispenses her own truth—a truth that both Bette and Schulman already know, and yet will continue to run up against as long as they maintain their ethics. “You want truth from people. You want them to be accountable. But they will never, ever take responsibility for what they really feel and do.”

*Correction, Mar. 17, 2016: This post originally misstated that the main characters of The Cosmopolitans lived in the East Village.